In the Spring of 2012, Obama campaign manager Jim Messina gathered a group of high-level Latino Democrats and operatives to update them on what they were doing to win support from Latino voters.

"I'm obsessed," Messina began, according to someone familiar with the meeting, "with the way Harry Reid's campaign did it in 2010. We're looking at that very closely."

Obama would go on to win 71% of the Latino vote, two years after Reid dominated with Hispanics in a tight race against a Tea Party candidate. The lessons from the Nevada senator were implemented.

"I operated based on what I knew and Sen. Reid was my training ground," said Nathaly Arriola, who worked on Hispanic press for the 2012 Obama campaign, which hired Latino communications strategists a year out from Election Day (instead of two months, as is often the case). The campaign polled Latinos early and often, and booked the president on Hispanic media. "It was a very regional approach to the way we communicated to Latinos and the issues they care about, because it was a winning strategy," she said.

When Reid exits the U.S. Senate in 2017, he will leave a complex and complicated legacy as an aggressive partisan legislator. He will also leave an equally complex legacy on immigration. Reid is the majority leader who could not pass immigration legislation with majorities in both Houses of Congress, but who pressured President Obama to go around Congress and take unprecedented executive action — an obsessive advocate for DREAMers, and a terse political operator who also used them for political ends.

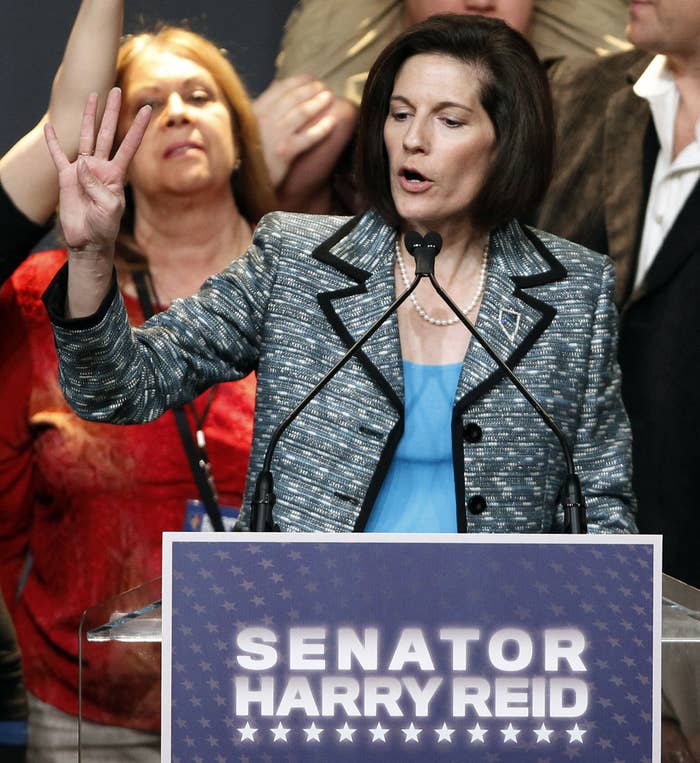

Reid's retirement was not a sure thing (before his accident last year, he had given indications he would run again) and came as a surprise to many on the Hill. But as he exits, Reid has also indicated early that he would support former Nevada attorney general Catherine Cortez Masto if she runs for his seat — she would be the country's first Latina senator, if elected.

"Whoever runs against Catherine, I think will be a loser," he said in a radio interview this week. "I hope she decides to run. If she does, I'm going to help her."

Two sources with knowledge of Reid's plans told BuzzFeed News that even if Reid's actual retirement was a surprise, his interest in an eventual Cortez Masto candidacy was not. "They really want her in the race, they feel strongly they think she can win. It's her decision to make but they completely and utterly support her," one said.

"[Reid] really likes her," another added. "He has considered her for a long time, she's a smart individual and somebody that can carry his legacy."

That help, in a state where Reid's influence and political machinery looms large, would be substantial. The Democratic women's group EMILY's List, which backs pro-choice Democratic female candidates, has also thrown its support behind Masto.

"We are excited about the opportunity to fill this seat with a strong, Democratic woman leader – which would be a first for Nevada," EMILY's List spokesperson Marcy Stech said in a statement. "Catherine Cortez Masto has been a fighter for Nevada women and families. She has a bright future and it's past time to elect the first Latina to the U.S. Senate."

Cristóbal Alex, the president of the Latino Victory Project, which fundraises for Latino Democratic candidates, also said Reid supporting the former Nevada attorney general is a big deal in a state that is almost 30% Hispanic.

"The way he's leaving, by highlighting and propelling someone who would be the first Latina U.S. senator, he would help make history and once again give back to the Latino community," he said.

But Reid remains known first as a partisan. His last race in Nevada was very close; this one will be in a presidential year (better for Democrats), but without Reid's long history on the ballot (not as good). The state is now governed by Brian Sandoval, a well-liked and more liberal Republican, and groups like the Koch-funded Libre Initiative are pouring resources into Nevada to early returns.

"If he's backing her, he's not backing her because she's Latina, he's backing her because she has the best chance of retaining that seat," said Luis Miranda, a former White House official.

The intrinsic politics to Reid's maneuvering on all issues, in the Latino community and far beyond, don't undermine the senator's legacy on immigration, Reid allies say. They credit Reid with changing the Democratic calculus on legal status and citizenship for the undocumented — turning immigration from a divisive wedge issue into a rallying cry for Democrats to coalesce around.

They say he created a pipeline of Latino staffers from inside his office and helped them advance on the Hill, with 15 currently on staff. ("He's not flying in operatives, he's breeding them," Arriola said.) And they trace his work on the Gang of Eight immigration bill, and the introduction and re-introduction of the DREAM Act, as significant markers in the politics of immigration over the last decade.

"On immigration he changed the game," said former Reid senior adviser Jose Parra. "Polls were showing that touching the DREAM Act was political suicide."

There is also the unusual role Reid, a senator, played in the executive actions implemented by President Obama in 2012 and 2014. Those actions followed years of either failed efforts to start an immigration legislative process, or gestures at starting a process unlikely to find success with Republicans, or even some Democrats. (In 2010, for instance, when Democrats still controlled both houses but were headed toward a blistering midterm election, Reid developed a habit of saying publicly and in press releases directed toward Spanish-language media that immigration legislation would happen soon, while admitting on Capitol Hill that it would not.)

Both in 2012 and 2014, it became clear that there would be no legislation moved. Reid began pushing the White House to forego Congress and implement what ultimately would be called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the program that delays deportation of some young undocumented immigrants and is the precursor to last year's executive actions.

Those with knowledge of what was going on behind the scenes say Reid's staff had worked up memos on how and why the administration should do DACA. The White House pushed back over whether they had legal authority to use prosecutorial discretion with a larger scope, and concerns that it was politically infeasible in the midst of a bitter campaign. At one point, Reid told senior administration staff that if they didn't do DACA, losing the White House for the party would be on them, according to a source familiar with the exchange. He left a memo from his staff on what they needed to do and walked out.

Reid then took it a step further, going on "Al Punto" with Univision anchor Jorge Ramos — a Spanish-language analogue to "Meet The Press" — and making a declaration of sorts.

"There's more the president is going to do administratively. And that should happen fairly quickly," Reid told Ramos on May 13, 2012.

The response from the White House was swift.

Miranda, the director of Hispanic media at the time, called Reid's office yelling and asking why he had said that, according to a source familiar with the period. Miranda laughed when asked about the story, saying he didn't remember that but that it was probably true.

"DACA was the big issue," said Arriola, who worked for both Reid and for the Obama campaign. "For Reid to come out strong, he did lead the pack. It was a timeframe when even our Democrat champions were not speaking up on this issue."

Some Democrats argue he can't be replaced when it comes to Latino issues, especially immigration, by Sen. Chuck Schumer who is very likely to become the new Democratic leader with Reid's endorsement.

"Fuck yeah, that's a loss," one longtime Latino Democrat said. "Schumer is like Rahm [Emanuel], their priorities are majorities and the bigger picture and if that means sacrificing immigration, so be it. Schumer has been a champion of immigration but also one of the people dragging their feet… Reid is more of a true believer, he stood by it on principle. Schumer is going to do it if it makes sense for the majority."

Another was more succinct. "I just don't see Chuck Schumer going to bat for the community like Reid did."

Complaints about Schumer highlight one of Reid's most Machiavellian strengths, namely his ability to shape different parts of the party's views of him on his own terms.

After all, Reid held off on serious efforts at rewriting immigration laws until President Obama wanted it done in 2013. But it is Obama and Schumer — and not the then-leader of the Senate, Reid — who are viewed as dragging their feet.

Inside the community of immigration activists, which played a significant role in pushing Obama from the left last year, Reid has his share of admirers.

He has frequently touted the experience of Astrid Silva, a Nevadan who was brought to the country as a child and who speaks highly of the senator, "For the first time I felt like I was protected and that was something I had never felt before."

Reid would have a direct impact on Silva's life in 2011, after her father faced the imminent threat of deportation, which the senator resolved by negotiating with ICE to get a stay of deportation because Carlos Silva had been scammed by a notario, someone who presents themselves as a lawyer, but is not. "His office was the first place I called, I didn't know what to do," she said.

There is a political dimension to this: Silva would later be prominently featured during Obama's event the day after announcing his sweeping 2014 executive actions, because her father is eligible to remain in the country if the program is ultimately implemented (the executive actions have been put on hold as they undergo legal challenge).

That political tension is not lost on the activists. When Gaby Pacheco, a high-profile DREAMer and activist, was asked to speak to the press after the DREAM Act failed in 2010, she was furious. She was angry about the legislation, but she also felt she was being used — a sympathetic face to throw to the media to bash Republicans — when she believed Democrats could have done more to get it passed.

With Reid by her side, she said her piece, but when it was over and the cameras were off, she grabbed Reid by his jacket and pulled him close, startling some of those present. She said Democrats could have done more and he knew that.

Reid, angered, pulled away from Pacheco and walked to the doorway before stopping.

Then he turned around, walked back to her, and hugged her, leaving the room bewildered about what had just happened.