WASHINGTON – From the 8th floor of a downtown Washington, DC, office building, seven people are the sole link between frantic callers on the mainland and loved ones they haven’t heard from since Hurricane Maria pummeled Puerto Rico.

A few hours with them underscores the chaos that is the Puerto Rico relief effort.

On one side of the long wooden table inside the conference room, Jose Gosende, 39, a volunteer from Virginia, was speaking with a woman trying to track down a sick uncle who was bedridden.

“I know it’s difficult but it’s important to remain calm,” Gosende said, scratching the back of his head through his dark brown hair. “My dad lives over there, too, and I haven’t heard from him in a week.”

Last week, the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration, Puerto Rico's representative office in Washington, became the main point of contact between the island and officials in DC. With communications to the island virtually nonexistent, the office launched a helpline to coordinate donations and help people contact friends or family. They idea was to take down caller’s information and enter it into a database that would be shared with authorities on the island who would try to locate people – with priority given to those with urgent medical needs.

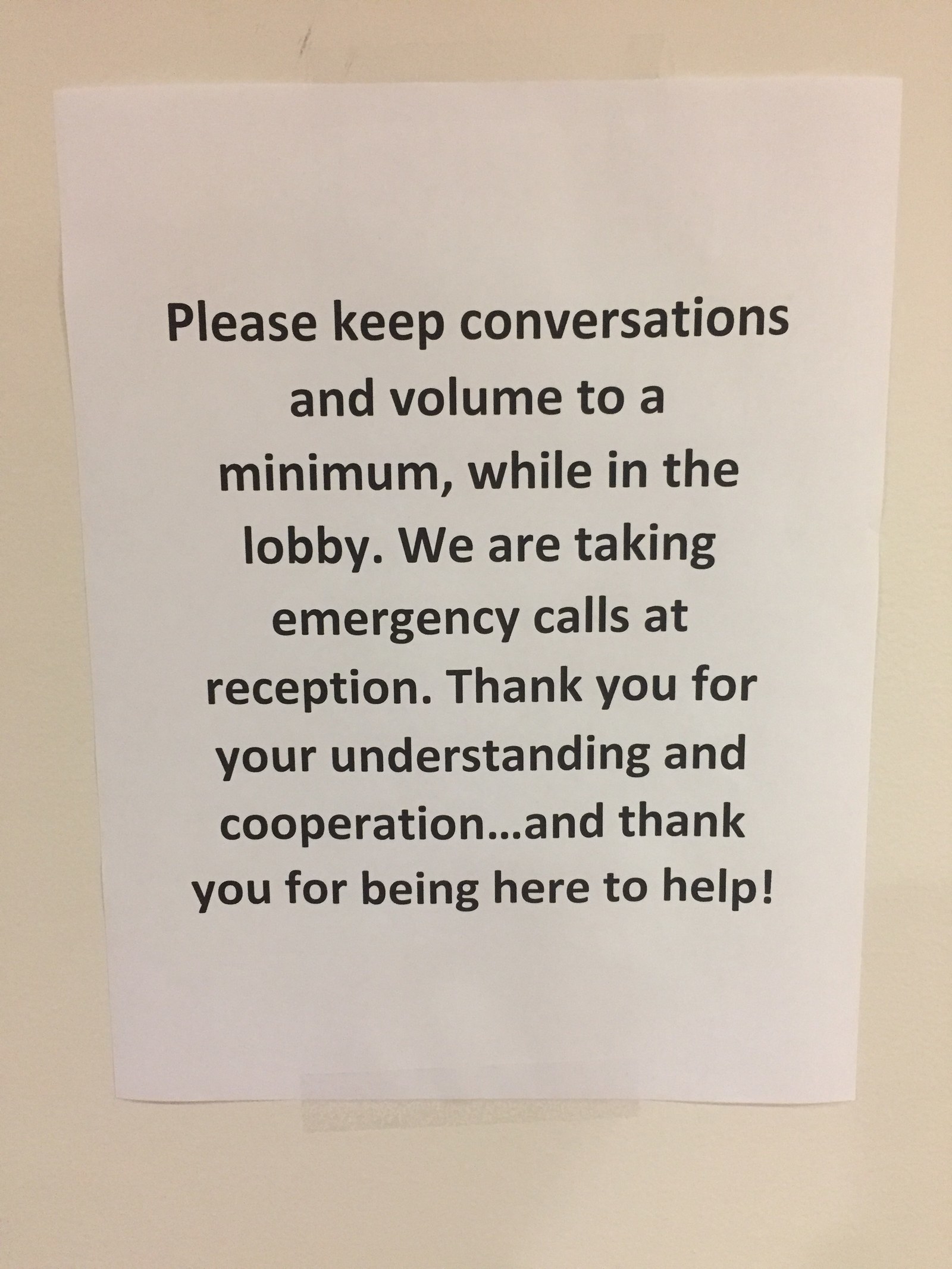

From the beginning, the phones never stopped ringing. Conversations, in both English and Spanish, were often difficult to make out in the din. There were thousands of desperate calls. Volunteers fielded them for hours, fueled by BBQ sandwiches, chocolate chip muffins, and coffee.

Every phone call reminded Gosende, who moved to the mainland 17 years ago to attend the University of Maryland, that he was not alone in his inability to reach loved ones in Puerto Rico. More than a week after the storm, thousands of stateside people still haven't heard that family members and friends are safe.

“I feel like I’m a therapist,” Gosende said.

Maria, a Category 4 hurricane that killed at least 16 people, has left more than 3.4 million US citizens without power, communication, or access to water and food. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-FL, has asked that the military be put in charge of the relief effort, though for now the Trump administration has left FEMA working with the Puerto Rico National Guard in charge.

“We’re basically in the same situation as the callers, we haven’t heard from our loved ones either,” said Ilia Torres, the legal adviser for the office. “The message we’re conveying to a lot of them is a message of sympathy because we understand what they feel.”

Torres said the office was inundated with volunteers right after it put out the call. A lot of people wanted to do something and not feel so helpless, she said.

“They’re pretty positive and energetic considering what they’re going through,” Torres said.

Denia Maldonado, 43, was in Madrid for a work conference when the hurricane struck. Instead of waiting in Spain until she could return to Puerto Rico, she flew to DC and crashed with a friend.

With her hair pulled back into a pony tail, the lawyer for Puerto Rico’s Justice Department switched between Spanish and English as calls came in, routed by a special software program to the volunteers' personal phones.

About 90 minutes into her shift on Wednesday, Maldonado had taken nearly 70 calls. The toughest one was a sobbing 18-year-old boarding school student in Virginia who hadn’t heard from his mother. The school put him in touch with the help line in an attempt to stop him from getting on a flight to Puerto Rico.

“Where is your mom located? Yeah the last I heard that area doesn’t have communication, only part of San Juan has it, and the rest of the island is very spotty,” Maldonado calmly told the 18-year-old. “What I can do is get your information and send it to various agencies on the island, like FEMA and other emergency offices, and if anybody reaches your mom they’ll contact you or your mom directly.”

Putting down her iPhone, Maldonado took a deep sigh.

“I came to college here in Washington. If at 18 I couldn’t get in touch with my mom, I would be just like him,” Maldonado said. “These are our citizens going through this. This is my family.”

Maldonado had only just heard from her husband the night before when he called at 2 a.m. from another person’s phone. She didn’t recognize his voice at first because he was sick.

“It was a relief,” she said. “It worries me when they call from a central area, the ones that have no access to roads. In one area, the bridges fell, and the only way to get in is helicopters. But I don’t tell them that.”

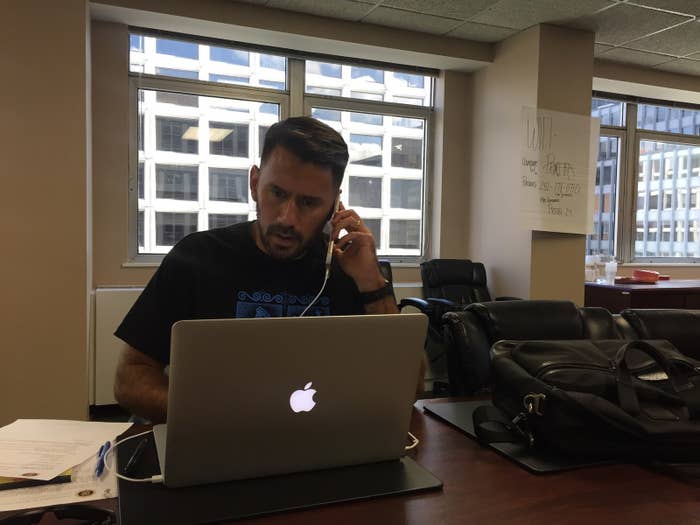

Carlos Mercader, the director of the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration, was inside a large dimly lit room with a representative from FEMA.

His cell would ring as soon as he finished with a call with another question or request.

“We realized fairly quickly that there was a big need to help people connect, and that’s how we started the phone bank,” Mercader said. “It’s devastating. Maria is historic in that we have never seen 3.5 million US citizens in the mainland without electricity, water, or means to communicate for six days.”

Mercader said they’re doing their best to coordinate with various agencies and people on the ground to get aid where its needed.

“We’re going to be working on this for a long time,” Mercader said. “The reconstruction of Puerto Rico is going to need the effort of everyone.”

Back inside the conference room, Gosende took a break and called an emergency management office on the island in the hopes of getting some information on his father. The line was down.

“Now I feel bad,” Gosende said. “I’m calling the number I gave people earlier.”