Andy Bales sat on the edge of his bathtub in February and considered his options: He could retire — in pain and with a foot that had nearly rotted off his body — or he could return to Los Angeles's Skid Row, the very place that had put him in a wheelchair.

He chose the latter.

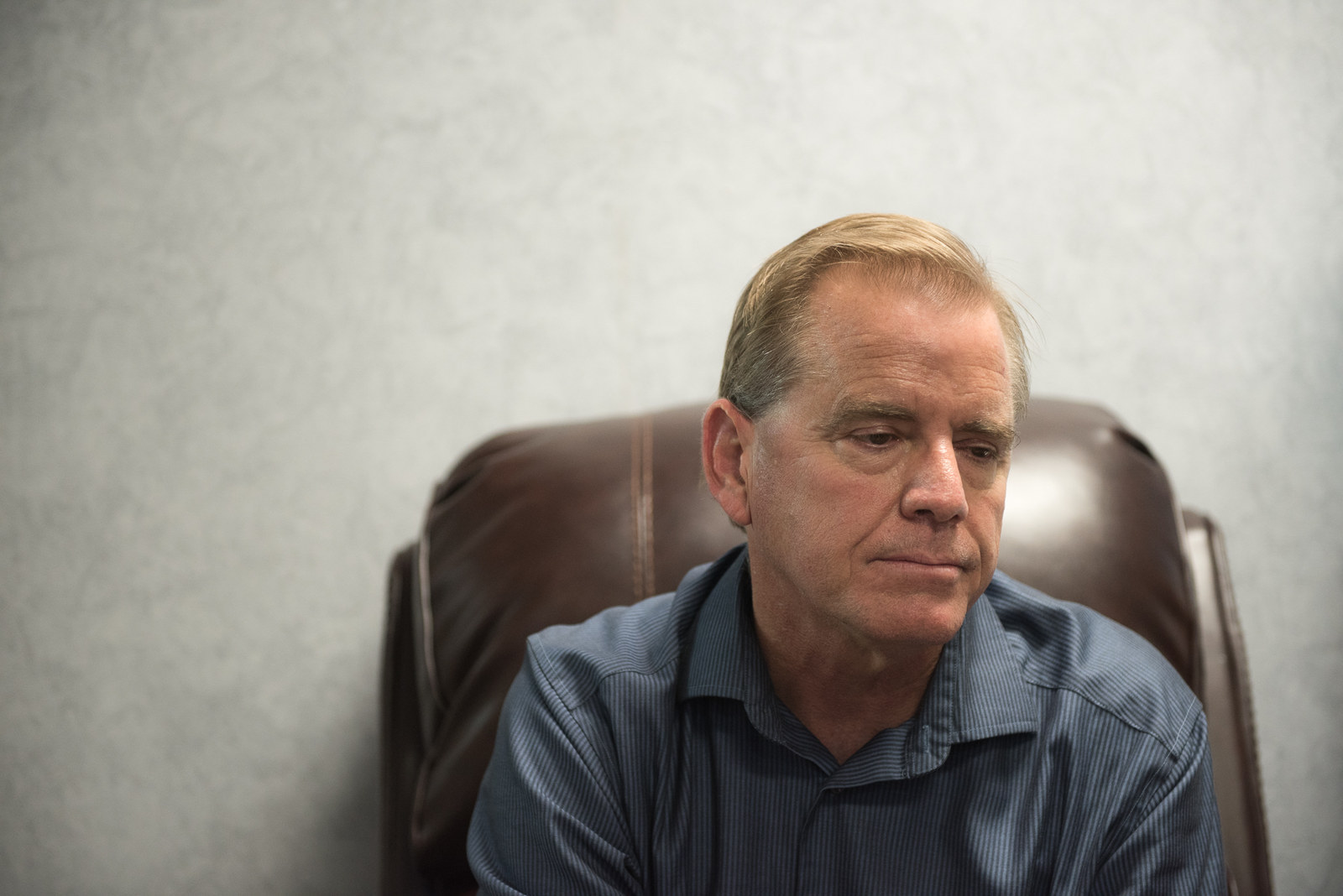

As chief executive of the Union Rescue Mission, Bales works on the frontline of L.A.'s hardcore homeless battle, where drugs, mental illness, violence, and disease make up the misery that is Skid Row.

“If I’m going to keep going, I have to manage the pain; if I stay home I’m going to have to manage the pain, so I better just keep going,” Bales recalled thinking. “I’d like to, in my lifetime, be a part of a movement that ends Skid Row.”

He has his work cut out for him.

When Bales isn't on the streets, he's managing one of the nation's largest homeless services providers, an operation that requires him to raise about $50,000 a day just to keep it running.

Every day, the mission serves 1,905 meals and houses 780 people overnight. And the demand shows no sign of diminishing.

Los Angeles city officials this year declared a state of emergency as the number of homeless marches upward, erasing previous gains.

From 2013 to 2015 alone, the number of makeshift shelters, including vehicles, increased a whopping 85%, or from 5,335 to 9,535, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority reported. And according to the last biennial homeless count, there were 41,174 transients in Los Angeles in 2015, up 16% from 2013.

At any given time, it's estimated that Skid Row is home to 8,000 to 11,000 homeless people, although due to the transient nature of the population, Bales says it is closer to 4,000.

Tent communities and piles of trash clog the roughly 54-block area of Skid Row.

The influx of transients in an area with little to offer in the way of public infrastructure outside gutters, storm drains, and a handful of public restrooms is also creating a a larger public health issue. In 2013, an outbreak of tuberculosis, which can be fatal if left untreated, put hundreds at risk.

“People are dying on Skid Row,” Bales said. “If we can’t get L.A. to be concerned about people dying on the streets, even if they only care about themselves, then we should address the conditions on Skid Row.”

In September, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced plans to invest more than $100 million to address the city’s homeless problem. At the time, Los Angeles City Council Member José Huizar, whose district includes Skid Row, called the scale of human suffering “astonishing.”

“It would literally take your breath away,” he said.

Andy Bales braves the heat to pass out water to Skid Row's homeless.

It was 2:30 p.m. on Sept. 30. In 88-degree heat, Bales gripped the wheels of his wheelchair and pushed himself onto a sidewalk, leading a group from the Union Rescue Mission into Skid Row to hand out water bottles.

The overpowering smell of urine and trash can at times be stifling. It was here, on a similar “water walk” in September 2014, that Bales believes his foot got infected via a nearly healed blister on his foot.

Infections on Skid Row — 54 L.A. blocks packed with thousands of people who are homeless, addicted to drugs, or down-and-out — aren’t uncommon. The city installed public toilets in the area, but many of them are controlled by gangs as places to shoot up or run brothels, Bales said.

But Bales’ right foot took a triple punch: Staph, strep, and E. coli infections took hold, but his immune system’s response was hindered by a 2013 kidney transplant that weakened it.

Days after that fateful water walk in 2014, Bales said he could barely stand as he prepared to board a flight to Raleigh, North Carolina. When he landed, his foot had turned into a giant blood blister.

Bales didn’t go to the hospital until about a week later, however, in part because he had also been treated for another wound in his right foot and believed the pain was related to the previous injury. It wasn't until he was flying home that the severity and pain caught up with him. By then, the infection had spread up near his waist, and doctors had to do extensive surgery on his foot.

"I should have gone to E.R., but I waited until Monday to see the doctor who is an expert with wounded feet," Bales said. "It was a stubborn mistake to wait and put me in peril."

As a result, Bales was hospitalized for four days and attached to an IV for about six weeks to kill the infection. Doctors also had to remove an infected bone from his ankle to salvage his foot.

“I was shocked — and yet not surprised — when I heard about what happened to his foot because for years we heard about bacterial loads in Skid Row going into the ocean,” said Natalie Profant Komuro, executive director of Ascencia, a homeless service provider in neighboring Glendale. “You have a really significant public health problem down there and at the end of the day, the disease doesn’t care about your socioeconomic background.”

Now Bales, once an avid runner, will likely spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair, his foot guarded in a black protective boot.

“I wasn’t happy about it, but I also wasn’t bitter or angry,” the 56-year-old said. “I just had to wrap my mind around the idea that I was going to be that guy in a wheelchair.”

The only photo Bales has of his grandfather is of him and a 14-year-old version of his father standing outside a tent in the foothills of Los Angeles County.

It wasn’t until Bales was 21 that his father revealed he had been homeless for a significant part of his youth, clinging to his father’s neck as they jumped freight trains from Des Moines, Iowa, to California in search of work during the Depression.

The family eventually returned to Iowa, where Bales’ father was a butcher at a packing plant before taking on a job at a feed company, where he eventually became its vice president. His mother at one point worked at a portrait studio before heading up a local rescue mission’s thrift store.

After earning a master’s in teaching at Drake University, Bales held several posts — book store clerk, teacher, city bus driver, parking ramp attendant — because of a recession and high interest rates saddling his home mortgage.

"It was humbling," Bales said. "At one time, I had three full-time low paying jobs and worked 120 hours a week. My kids called me the uniform man."

Eventually he was able to transition to working in homeless ministries in Des Moines from the mid-1980s to 1999.

“The physical infirmities that he is currently dealing with today have not stopped him one bit. He just keeps going.”

He moved to Pasadena, California, in 1999 for a job at Lake Avenue Church and Foundation. For years, Bales tried to increase outreach to the city’s homeless population, but he said his concerns fell on deaf ears and eventually left him without a job when he drew the ire of city officials.

Then in 2004, when he was unemployed and sitting in his front yard, Bales got a call offering him the position of president at Union Rescue Mission, telling him it was in preparation to become the nonprofit’s chief executive.

Since then, Bales has become one of Los Angeles County’s most prominent advocates for the homeless, using the powerful pulpit of the Union Rescue Mission to push and prod elected officials for more services.

Huizar told BuzzFeed News in a statement that he admired Bales for helping thousands of transients get their lives together and offering hope to people who often have little.

“The physical infirmities that he is currently dealing with today have not stopped him one bit. He just keeps going,” Huizar said. “He’s a reminder that in order to address homelessness we are going to need a lot of persistence.”

Navigating the tents, trash, and passed out transients on Skid Row is tough enough, but doing so in a wheelchair makes it that much harder.

When the massive infection took hold, Bales had asked doctors to amputate his right foot, which he said was pockmarked with “gaping holes.” A prosthetic would at least allow him to run and swim, he thought. But his doctors declined on the grounds that his foot hadn’t deteriorated to the point where amputation was necessary.

“People say, ‘Don’t give up hope,’” Bales said. “But if they saw my foot and ankle, they’d know without a doubt that it can’t be fixed.”

Whatever the outcome for his badly damaged foot, Bales said he has every intention of carrying through with the decision he made that day on the edge of his bathtub. Skid Row may have physically battered him, but his spirit remains indomitable — although he acknowledged the emotional toll it can take, especially when it involves children.

“I cry on my way home; I get up in the morning and start brand-new,” Bales said. “It’s because of the hope that I have, and because I get to see walking miracles — I get to see lives that are transformed.”