TIJUANA, Mexico — Viridiana Morales’ family arrived at the border in Tijuana filled with hope. They’d escaped the death threats from drug gangs in their hometown near Acapulco and would soon be safe in the US, or so they thought.

Then they got the bad news when they arrived at the San Ysidro port of entry that connects Tijuana with San Diego: They’d have to wait five to six weeks before they’d be given the chance to ask for asylum. Morales felt sick.

“It was so discouraging,” Morales told BuzzFeed News. “We were fleeing violence, didn’t know where to go, didn’t have a lot of money, and now we had to wait for weeks.”

Morales’s family is among the hundreds of asylum-seekers who are doing what the Trump administration says people like them should do — wait their turn at a port of entry instead of crossing the border illegally and then asking for refuge. On Friday, the administration enacted policies that would bar people from obtaining asylum if they cross the border anywhere other than at a port of entry. The new rule changes years of US policy that allowed a migrant to request asylum from any US border officer regardless of how they entered the country.

Immigrant advocates say the policy is inherently unfair because the wait is so long at the ports of entry, and the US is doing nothing to speed the process. Forcing asylum-seekers to apply only at ports of entry is going to make an already sluggish process even slower.

As of Friday, there were about 1,000 people waiting to ask for asylum here, and newcomers were being told they’d have to wait three to four weeks for their turn.

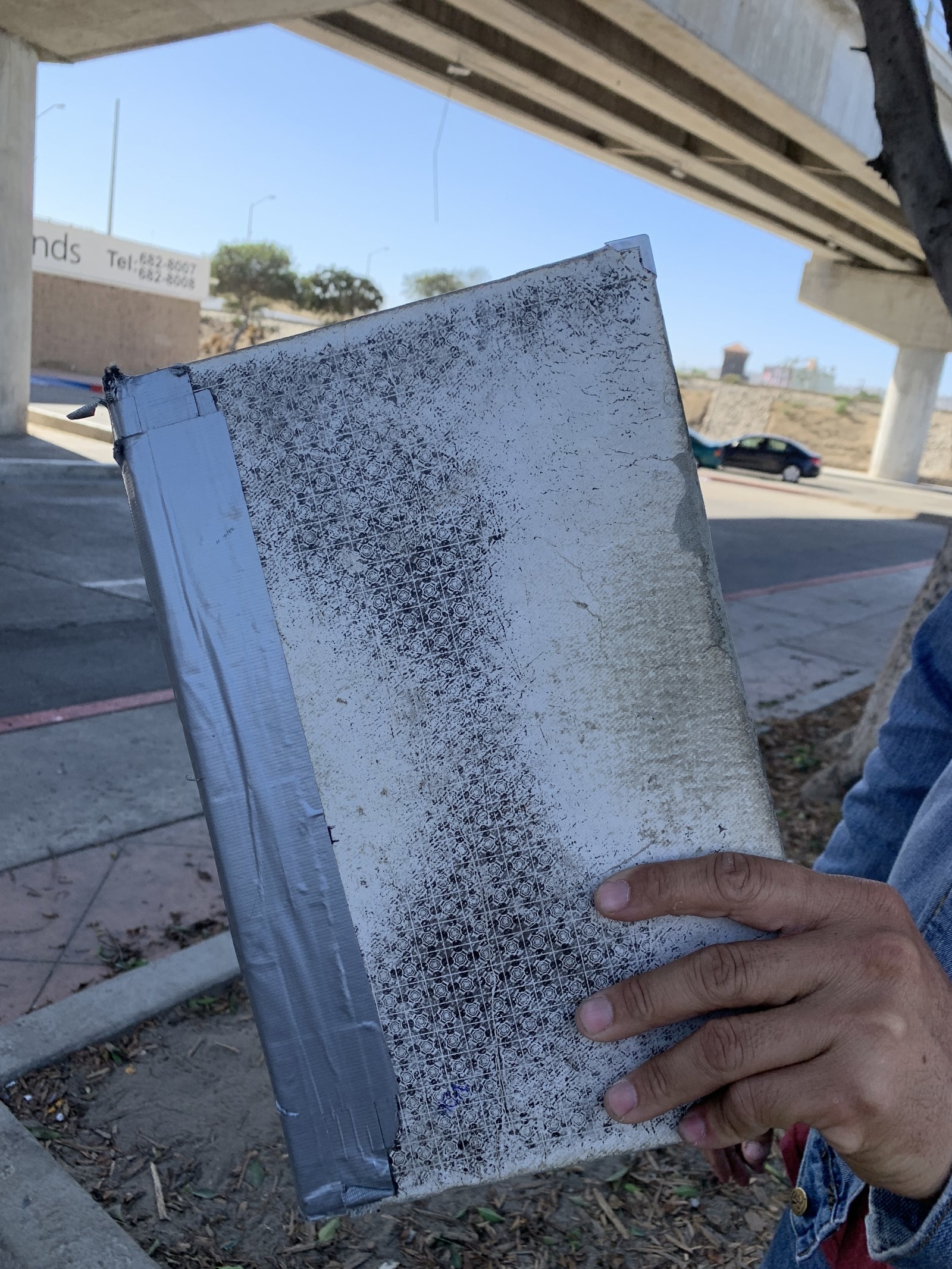

To add to the sense that the asylum application process is stretched thin, the current keeper of the waiting list is a Venezuelan who’d like to seek asylum himself. Roberto Sanchez, 33, was handed the list, which is maintained in a thick, battered white notebook with a spine that’s held together by duct tape, by another migrant whose time to apply for asylum had arrived, and when it’s his turn to meet with US border authorities, Sanchez’ll pass the responsibility to another waiting asylum-seeker. Officials from the humanitarian arm of Mexico’s immigration enforcement agency, known as Grupo Beta, will then walk Sanchez to the metal gates that mark the actual entry into the United States, where his asylum claim will be processed.

United States border authorities limit the number of asylum-seekers they’ll let through the gates through a process called metering, citing a lack of space for the number of people at their doors. A government report made public in October found that the practice of turning away asylum-seekers and making them wait in Mexico likely forces people to cross illegally.

For the last five weeks, Morales’s family has found refuge at a nearby migrant shelter, waiting for their number to be called. Of all the families in the shelter, they’re among those who’ve been waiting the longest, and they’re expecting to cross into the US on Saturday.

The family fled the Mexican state of Guerrero because a gang member told Morales’s husband he had to join their crew. He was told to present himself at a gas station on Oct. 6 or the entire family would be killed. Instead, they fled with the clothes on their back and two backpacks for the Tijuana border before dawn two days before the deadline, and eventually found themselves at the shelter.

On Friday afternoon, groups of families sat around a table playing a Latin American card game that's similar to bingo, while a group of girls played with each other’s hair nearby. All of them were waiting for their turn.

Morales doesn’t want to get her hopes up. Just last week, the family thought they were going to be called, and instead were told by other asylum-seekers at the San Ysidro port of entry that the doors had been shut indefinitely. It wasn’t true — US Customs and Border Protection just didn’t have enough space — but Morales was devastated.

“I started to cry, because you go thinking it’s your turn and it’s not,” Morales said. “You’re recounting all the bad things that happened to you in your head; you feel so close. It’s just a great sadness.”

The mother of two kids, a 12-year-old son and an 11-year-old daughter, said she can see how desperate parents leave ports of entry and pay smugglers to get them into the US undetected.

Nicole Ramos, the Tijuana-based director of the border rights project for Al Otro Lado and who focuses on refugees seeking asylum in the US, was at the Tijuana–San Diego port of entry on Friday morning, meeting with newly arrived families.

She’s concerned that potential asylum-seekers won’t know that they won’t be able to ask for refuge if they cross the US–Mexico border illegally, and that the wait times at ports of entry could double if more people come.

“The US will probably stop admitting everyone or slow it down to an absolute trickle,” Ramos told BuzzFeed News. “People here waiting are sitting ducks for organized crime. I’ve spoken to many women fleeing domestic violence and families fleeing cartel violence who receive messages from their abusers saying they know they’re in Tijuana.”

Nearly 400,000 people were apprehended between ports of entry at the southwest border in the last year, according to figures from CBP. US officials have made that figure sound dire this week, but the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) found that it was actually the fifth lowest since 1973.

But the number of apprehended migrants traveling with children has hit a record high, WOLA said, accounting for 40% of apprehensions in the last year; in 2012, families made up only 10% of apprehensions.

It’s those families that end up seeking out Border Patrol agents once they cross into the US illegally to press an asylum claim.

An analysis from WOLA also found that following former attorney general Jeff Sessions’ “zero tolerance” policy, which attempted to prosecute every migrant who crossed illegally and push them into ports of entry, border agents “notably slowed” their reception of asylum-seekers.

“During March, April, and May 2018, more than 6,000 children and families reported to ports of entry as what CBP calls ‘inadmissibles,’” the analysis said. “Every month since June, however, the number of children and families at the ports has held mysteriously steady at 4,000 per month, even as ‘zero tolerance’ was encouraging them to approach the official crossings.”

The Trump administration has blamed a spike in recent border apprehensions, though historically low, on migrants taking advantage of the immigration system and filing unfounded asylum claims. Officials like Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen have said that the threshold for getting a positive determination during a credible fear interview, a crucial first step in the asylum process where people express a fear of persecution if they’re returned home, is too low.

In announcing the new regulation for asylum-seekers, US officials said that of 11,307 people from the Northern Triangle countries — El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala — who passed their credible fear interview and completed their cases in fiscal year 2018, only 17% ultimately were granted asylum by immigration judges.

Carlos Yee, program coordinator at Casa del Migrante, a shelter in Tijuana for migrants, said the wait times can be especially discouraging for Central Americans who traversed all of Mexico thinking their struggles would end once they reached the US border.

“The emotional impact of being turned away is strong,” Yee said. “People feel hopeless.”

Yee said the lack of capacity at ports of entry is only a problem because the United States doesn’t want to make more space available to meet the demand of asylum-seekers.

The proclamation Trump signed Friday directs the secretary of homeland security to commit “additional resources” to ports of entry along the border, but asked about that on a call with reporters, DHS and Justice Department officials didn’t provide details. An official said there were “ongoing” discussions.

Morales was unaware of the changes expected to take place at the border at 12:01 a.m. ET Saturday, but hoped it wouldn’t affect her chances.

“I’m not going to risk my kid’s lives crossing the desert, so our only option is to wait for our number to be called,” Morales said. “There’s a better future waiting for us if we ask for asylum with the permission that only God and the United States can give us.”