This is an excerpt from Please Like Me, BuzzFeed News’ newsletter about how influencers are battling for your attention. You can sign up here.

When Claude Lukyamuzi pressed send on a seemingly innocuous tweet, “I don’t Google anymore I TikTok,” he never anticipated the reaction would be so polarizing and also telling of evolving user behavior.

I don’t Google anymore I TikTok

With 5,000 comments, 25,000 retweets, and 100,000 likes, the viral post generated responses ranging from those who declared TikTok the search engine for Gen Z, and others who insisted that people agreeing with that statement showed “society is doomed.”

“The tweet was so simple, but a lot of people also agreed,” Lukyamuzi told BuzzFeed News.

Indeed, one of the thousands of likes was my own, as I routinely find myself diving into the “dancing app” in search of things like restaurant recommendations, holiday destinations, and hacks on how to maximize suitcase space before a flight.

Just like the advent of YouTube, the school of TikTok has provided a platform for academics, healthcare professionals, lawyers, construction workers, and more to lift the veil on their professions and, in doing so, share a wealth of knowledge that has been previously gatekept or isn’t always easily accessible.

Today, #tiktoktaughtme has 6.6 billion views. Under the hashtag lies a plethora of video examples of hacks and advice that, for some, have been transformative, whether that’s learning sign language, or how to deep-clean a bathroom, or why you cough when a drink goes down the wrong hole.

But there are limits to the platform — as we saw recently with constant videos and viral audios questioning Amber Heard’s testimony from her trial against Johnny Depp. The platform was recently named as being instrumental in the spread of misinformation in the run-up to last month’s presidential election in the Philippines, with Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the son of dictator Ferdinand Marcos, securing a landslide victory after a successful campaign that essentially rewrote history and glamourized the Marcos name on TikTok. At the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, fake TikTok content was a constant problem, with videos of old conflicts and pro-Putin propaganda being circulated. In mid-2021, videos of people using a debunked COVID cure, the horse dewormer drug ivermectin, were constantly spreading across the platform.

People may use TikTok as a search engine, but that doesn’t mean the information posted — particularly around breaking news, health, and politics — is always accurate or factual.

Lukyamuzi, a 24-year-old product designer from London, shared that TikTok had become his go-to place for searching for things like getting insider knowledge on the best airlines for travel hacking, but still occasionally returns to platforms including Google and YouTube to verify certain pieces of information. He said the way people respond to content on TikTok can form its own vetting service.

“I feel like I could have consumed information that has been false, but how I decide whether I can trust it is with the catalog of content people put up previously and the response from the comments,” Lukyamuzi said.

TikTok comments, however, can be just as misinformed as the content itself, as Dr. Casey Fiesler, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, pointed out in a recent Twitter thread.

“I just saw a comment on TikTok that Planned Parenthood performed 400 million abortions last year,” Fiesler tweeted. “Just presented as absolute straight-up data. That is like three times the total number of female humans in the United States.”

For years harmful misinformation spread across social media platforms has negatively impacted society. Facebook, long considered a playground of misinformation and disinformation targeting older users, has encouraged the spread of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, the proliferation of far-right lies, and the genocide of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

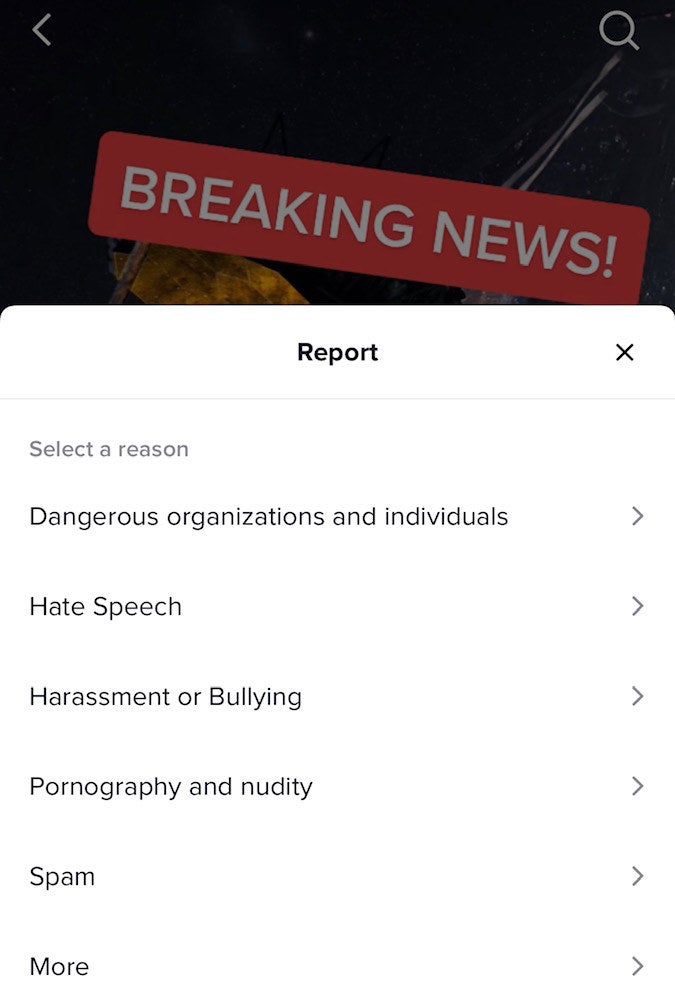

After years of outcry, both Facebook and Twitter now at least put warning labels on some posts that spread misinformation. TikTok has adopted an “unverified” flag for videos during breaking events, but it doesn’t appear as widespread as on other platforms. Comments can be flagged for hate speech, harassment, or spam, but not for being factually wrong.

TikTok’s transition to a more vlog-friendly space has led to a rise in content that is often very personal, testimonial, and to the right audience, accepted as gospel.

While it may be of value, the format where people share what they’ve been through or seen means misinformation may be in the eye of the beholder: One fact may be incorrect, but the user’s feelings and experience may be accurate. “A lot of times when people are searching for information, what they actually want is someone's personal experience,” Fiesler said.

The present conversations about TikTok becoming Google for Gen Z are not too dissimilar to early comments when YouTube gained popularity among millennials as a search engine.

“That's not something new, necessarily,” Fiesler said.

With 1 billion active monthly users, I agreed with Fiesler when she said TikTok is “as important as any other platform” when thinking about the problems with misinformation.

Snark aside, how do we navigate this growing audience of users who are getting more and more comfortable with relying on the platform as a source of valuable information when the platform itself doesn’t seem to be overly concerned with the spread of misinformation? Fiesler said TikTok users should be ready to be more critical of the information they are consuming and vet sources.

“That's not to say that everything a random person on TikTok without credentials is saying is a lie, but you just have to know the difference between knowing that this is true, and thinking, Oh, I should look that up, or Oh, I should see what other people had to say about this or, you know, that that's true, because we so often believe something immediately, just because we want to believe it,” she said. “Confirmation bias.”

As with any platform, the pivot to TikTok as a search engine has its shortcomings, and as social media companies grapple with the task of keeping platforms safe, transparent, and accurate, again the burden falls unfairly on the consumer to evaluate the content they interact with.

Learning to vet information is a skill we all need to practice — so look at what other content an account has posted, be wary of personal accounts posting breaking news, don’t automatically post something without double-checking, read the comments, and see the stitched videos to see if others have discovered something you haven’t yet.

TikTok is a great search engine for lifestyle and general life content, but let’s be skeptical of it as a news source.

In the words of rapper Fredro Starr, there is always value when you “do your googles.”