This is an excerpt from Please Like Me, BuzzFeed News’ newsletter about how influencers are battling for your attention. You can sign up here (and you should, ’cause we just revamped it).

There was once a time when being caught wearing a knockoff designer item could tank your reputation, but fancy fakes now look and feel nearly as good as the originals, so people are wearing them with pride.

“I was so close to buying the real thing,” British blogger Georgia Maiy told her 240,000 followers on TikTok as she unwrapped a tightly bundled package to reveal a bright orange box.

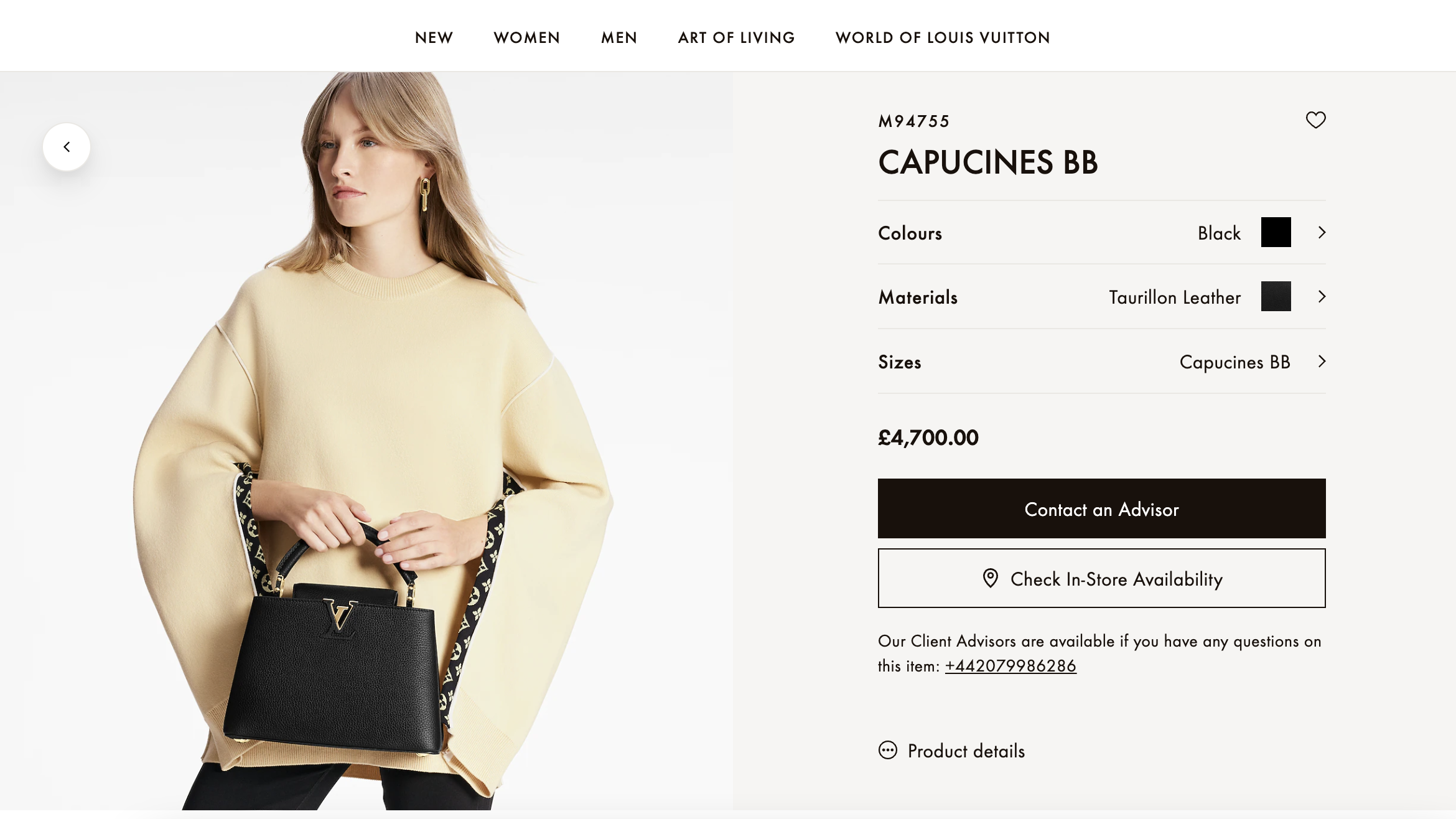

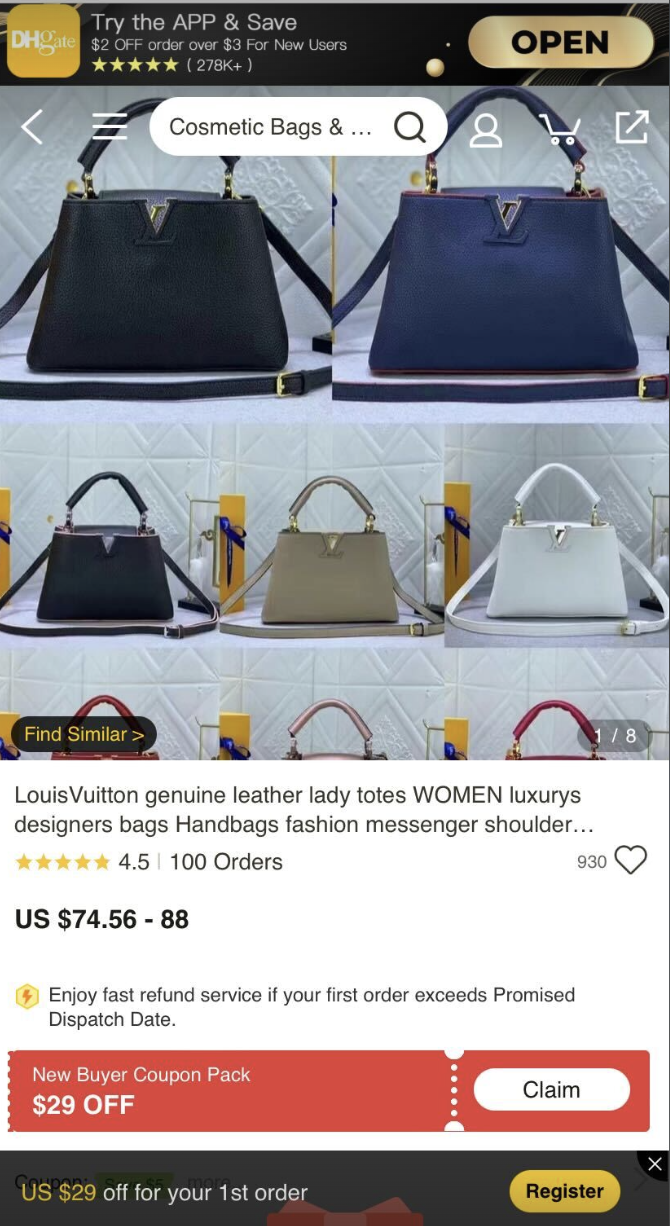

“It’s about £3,000. It’s so expensive,” she continued. The influencer beamed with pride as she showed off her $75 knockoff of Louis Vuitton’s Capucines BB handbag, which retails for $6,750.

As the economy shifts, designer replicas — not to be confused with a dupe, although regularly tagged as such — are increasingly more socially acceptable, and data from the European Union Intellectual Property Office found that members of Gen Z are big fans, with 37% of respondents intentionally buying a fake product in the last year.

A search on TikTok for content tagged #DHgate, a Chinese business-to-business marketplace and prolific destination for designer knockoffs, has 3 billion views of people flaunting their purchases that traditionally would have signaled wealth but instead cost a fraction of the retail price.

“DHgate is super notorious — you either love it or hate it,” said Jeffrey Huang, a 28-year-old luxury lifestyle and travel influencer from Boston. “It ruins luxury for influencers because we work hard to be able to purchase these items and there are people who buy dupes or fakes and claim it as authentic.”

But is it maybe OK if luxury is ruined? Influencer culture has supercharged consumerism and promoted the idea of having a personal brand for online presentation, with expensive, high-end label items often a part of the desired look. But fake products look basically the same in photos.

From “Black girl luxury” to the “old money” aesthetic, appearing affluent is aspirational — and influencers are hacking their way into the trend with the help of counterfeit goods.

Today, the world of knockoffs has elevated beyond ticking Rolexes or Ralph Lauren polos with a donkey logo — they’re far more sophisticated and come with a cleaner finish that competes with the real deal.

The taboo of wearing counterfeit designer clothing still carries a certain weight of shame in some cultures, as Song Ji-a, an influencer and the breakout star of Netflix’s Korean dating show Single’s Inferno learned, after a few fake pieces of Chanel and Dior prompted outrage to which Ji-a responded with a handwritten apology note.

But the volume of the counterfeit designer industry is estimated to be worth between $400 billion and $600 billion by the US Intellectual Property and Counterfeit Goods Office. This has been met with the need for an authentication industry to distinguish between what’s real and what’s fake.

For advocates, who proudly flaunt their fakes, buying a counterfeit is primarily about being financially savvy, especially at a time of economic uncertainty.

Just a year before finding fame on Season 5 of Love Island, Molly-Mae Hague was another YouTube influencer directing her subscribers on where to find designer knockoffs and look “boujee on a budget.”

Young consumers want to tap into the credibility of these brands but avoid plunging themselves into debt to try and keep up appearances.

For some consumers of high-end fake designer clothing, their purchases are considered a small act of defiance against an industry that has thrived on scarcity and being exclusionary of specific demographics.

“I think it's a great opportunity for people to use it as activism and say, ‘You know what? You don't make clothes for me, but I still want to wear your stuff,’” said Brett Staniland, a model and sustainable fashion creator.

He noted that some people might say, “I don't care that this is fake because I deserve to wear clothes that look good and make me feel good and celebrated regardless of whether they're real or not.”

The normalization of counterfeit items is a point of contention for traditional luxury lifestyle influencers like Huang, whose videos include $17,000 hauls at Louis Vuitton. Unsurprisingly, he considers this counterfeit trend harmful as, he said, these fake items are now entering the secondhand retail space. A viral TikTok alleges the problem also extends to department store shop floors.

“This hurts people who can’t afford to buy authentic luxury goods brand new,” Huang said. “So they buy preowned, and these fakes end up infiltrating the used market. So people unknowingly spend their hard-earned money on fake thinking it is real.”

Similarly, Staniland expressed some concern about the ethical implications.

“Someone somewhere made these items, and they also deserve to be celebrated and make sure that they're valued, paid for living wages, and included,” he said.

The fashion advocate was also critical of the way the counterfeit industry robs designers of their intellectual property.

“It's all well and good finding things that are knockoff designer, but ultimately, some of these designers deserve to be celebrated and they don't deserve their work to be appropriated,” Staniland said.

Criticisms have long been levied against luxury lifestyle influencers, who for all intents and purposes are very clear on what their content consists of but have been accused of being out of touch with the economic realities of their audience and creating wealth porn content.

But Huang, who has over 200,000 followers on TikTok, said people look to him for aspirational videos irrespective of their income, and he was unapologetic about his love of high-end items.

“They tell me they can’t ever afford these items and they are going through financial problems, but they live vicariously through me,” he said.

“I am still creating luxury content even though we are still feeling the effects of a pandemic,” Huang added. “TikTok is living proof that there are so many people who enjoy this content.”

As fast-fashion brands like PrettyLittleThing and Boohoo attempt to pivot to a greener and allegedly sustainable era with celebrity faces attached, luxury brands continue to battle the challenge of mass-market knockoffs.

Creators stripping away the taboo of fakes in the pursuit of a luxury aesthetic will inevitably leave someone at a loss, whether that be the design houses, manufacturers, department stores, or a confused consumer. But when the content looks just as good — and with inflation over 9% in both the US and UK — it’s unsurprising that creators are prioritizing themselves over brands or the broader ethics of what they’re indulging in.

UPDATE

This piece has been updated to clarify a quote.