More than four decades after it entered the lexicon, the phrase “drinking the Kool-Aid” has slowly become detached from its referent: the Jonestown Massacre of November 18, 1978. On that day, more than 900 members of a California social movement known as Peoples Temple died in a mass murder–suicide at the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project in Jonestown, Guyana. The suicides occurred shortly after armed members of the Temple ambushed a party of defectors as they attempted to board two airplanes in nearby Port Kaituma along with congressman Leo Ryan, who had gone to Jonestown to check up on some of his constituents. The hitmen killed Rep. Ryan — to date the only congressman assassinated in the line of duty — as well as one of the defectors and three members of the press. Altogether, the Jonestown Massacre was the largest loss of American civilian life on a single day until the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Many of those who took their lives in a purported act of “revolutionary suicide” — a phrase that Temple founder Jim Jones had misappropriated from Black Panther Huey Newton — did so by knowingly ingesting Flavor-Aid laced with tranquilizers and cyanide. They believed their “last stand” was a statement posterity would remember: the Temple’s final position was that it was better to die together, as socialists united to the cause of equality and freedom, than be forced to return to the racist, sexist, and classist society they had left behind in the United States. Although the stated reasons for the dramatic mass suicide are not often remembered, the method of self-annihilation certainly is: since 1978, the idiom “drinking the Kool-Aid” has been used to denote behavior that exhibits blind and unquestioning obedience to an individual or organization.

Although the Jonestown murder-suicides took place in a small Socialist country on another continent, the inescapable and indelible imagery of the tragedy — in which Americans saw hundreds of bloated bodies strewn around the Jonestown pavilion — brought an end to what had been a relatively tolerant attitude toward idiosyncratic religious movements in the United States throughout the 1970s. The Jonestown tragedy reinvigorated an otherwise flagging trend known today as the anti-cult movement (ACM). This “movement” had its roots in the traditionalist response to countercultural activity in the 1960s, and is part of a longer cycle of cult/anti-cult activity in American culture, including the seventeenth-century witchcraft panic, the nineteenth-century anti-Masonic movement, and the anti-cult movement of the 1940s.

Although the “revolutionary” suicide of Peoples Temple was a uniquely grotesque and terrifying event, the decision to die at Jonestown was consistent with aspects of Temple political ideology and what might be called its theology. Peoples Temple emerged from the long and continuous tradition of messianic communalism in the United States. Across more than 200 years of American history, schismatic Christian sects emerged in opposition to what they viewed as the apostasy of American Protestant churches that increasingly acted as handmaidens to a capitalist order based on exploitation.

As an act of purification, these groups often expressed their separation from the corrupting decadence of capitalist society by withdrawing from the formal economy altogether, or insofar as that was possible. They strove instead for communal self-sufficiency. Many of these groups described their communal societies as a return to the communism practiced by the first groups of Christians mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles, who renounced personal possessions and practiced the community of goods. The most successful and enduring Christian communalist sects were led by individuals who claimed messianic stature and a God-given mission. Messianic sects like the Shakers, the Universal Friends, the Brotherhood of the New Life, the Koreshan Unity, and the Peace Mission were a consistent feature of the progressive Left of religious culture in America. Peoples Temple was a direct descendant of this lineage, and Jim Jones conscientiously fashioned himself after the black messiah known as Father Divine.

Nevertheless, the media and the vast majority of the American public turned not to religious scholars for explanation and understanding of Peoples Temple, but to self-promoting psychologists and other “experts” affiliated with the anti-cult movement. They did so because ACM activists cast themselves as so many Cassandras who had been sounding the alarm for the entire decade that Peoples Temple amassed the majority of its followers.

Thus — and rather ironically — the truly American response to the Jonestown tragedy was characterized by a strong entrepreneurial current: A cottage industry of professionals, ranging from academic psychologists to rebranded bounty hunters calling themselves “deprogrammers,” emerged to steer Americans out of the clutches of putatively demented cult leaders. Professional deprogrammers, the term used for those who claimed to specialize in undoing the effects of brainwashing, went on Donahue and testified before congressional committees about the continuing dangers of cults hidden in the midst of Reagan’s America. The cult menace remained a national obsession until it was finally eclipsed by the emergence of global jihadism early in the twenty-first century. As a result, any group engaged in that very American activity of critique, separation, purification, and regeneration became subject to social sanction and government scrutiny.

The anti-cult obsession had deadly consequences for the Branch Davidians, a messianic society led by Vernon Howell, a prophet who had taken the name David Koresh. Responding to allegations that the Davidians possessed illegal firearms and engaged in aberrant sexual practices, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms sent more than seventy armed agents and two Blackhawk helicopters with a warrant to search the Davidians’ complex of buildings at Mount Carmel outside Waco, Texas, in February 1993. Following a violent confrontation and the subsequent fifty-one-day siege of the property by the FBI, Attorney General Janet Reno concluded the standoff by authorizing the bureau’s plan to assault the cornered Davidians. The attacks ended up killing four agents and at least seventy-four of the Davidians, most of whom died in a fire that razed the building where they were under siege. Ironically, the use of force was publicly justified by constant appeals to the horror of Jonestown, which stoked fears that the Davidians would commit mass suicide rather than surrender. There was no evidence that the Davidians ever intended to do so—but in any case, they were murdered before anyone could know for sure. Their classification as members of a “cult” made the killings acceptable, if not inevitable, in the eyes of many Americans.

Evading the “cult” label is imperative for any minority religion that hopes to avoid a violent and tragic end. In the 21st century, a new messianic religion has so far managed it. Concentrated in Silicon Valley, the latest amalgamation of old American messianic tropes has gathered under a techno-futurist, New Age banner emblazoned with the word “Singularity.” Although the Singularity refers to an event, specifically a moment of technological rapture, it is, like all American messianic religions, more of a mindset than a coherent belief system. Adherents to the movement are growing in number, and their plans for redesigning life as we know it have become increasingly grandiose. Fortunately for these devotees, the Singularity movement has largely evaded perception as a cult-like organization. It has done so by avoiding, for the most part, the dangers of conflating human salvation with the destiny of a single individual, and by reconciling American messianic thought with its old adversary: capitalism.

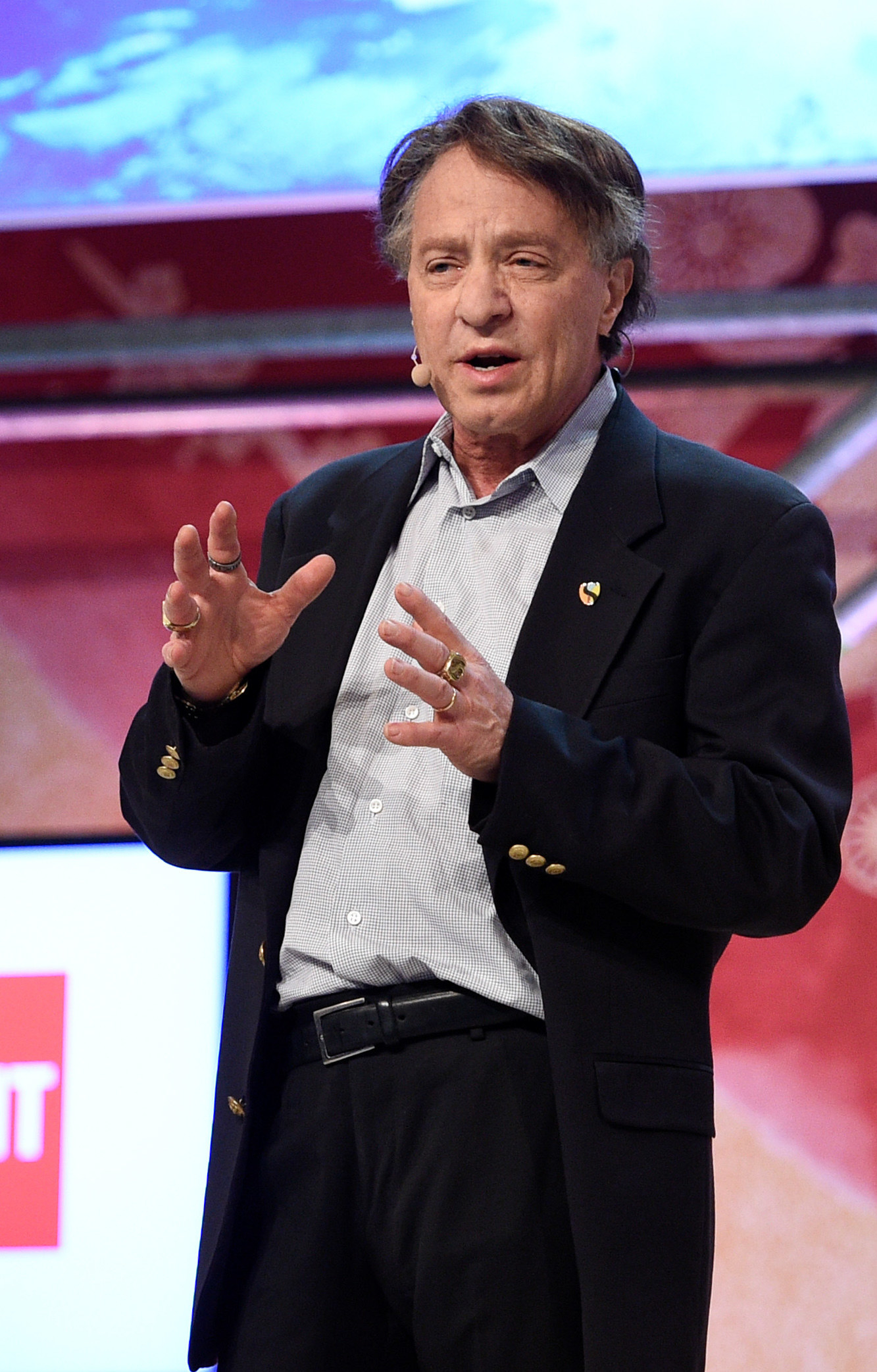

Adherents to the movement are students of the work of Ray Kurzweil, a septuagenarian futurist and entrepreneur. Kurzweil believes that within his lifetime, a historical achievement known as the Singularity will allow humankind to ascend to the next level of evolutionary existence: its inseparable union with artificial intelligence. In fact, the Singularity will render the distinction between human and artificial intelligence largely irrelevant, as they will become increasingly imbricated and difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish. In Kurzweil’s view, intractable problems like climate change, resource scarcity, sickness, and even death will be eliminated by the Singularity, not least because it will liberate humankind from the organic prison of carbon-based bodies.

In his book The Age of Spiritual Machines (1999), Kurzweil claims that humans will “become software.” As a consequence, he writes, “there won’t be mortality by the end of the twenty-first century.” Kurzweil likes to describe the advances enabled by the Singularity as a logarithmic upturn on the evolutionary curve. He believes that his work is hastening the evolutionary development of the human species into something that can no longer be called strictly human. Like Thomas Lake Harris and Cyrus Teed, two of his forebears in American messianic thought, he sees a new race evolving to supplant the old “corruptible,” decadent, miserable humanity. His evolutionary, deo-morphic theology is not unlike theirs; nor is plugging into the Singularity all that dissimilar from the attunement to Abundance extolled by Father Divine, or the mission to become as gods on Earth under the holy regime of apostolic socialism proclaimed by Rev. Jim Jones. But unlike his predecessors, Kurzweil believes that capitalism is not the engine of damnation, but of salvation.

Enthusiasts of the Singularity believe the unfettered free market, particularly the one in Silicon Valley, will bring about the quantum rapture they eagerly await. Opponents of the movement decry its uncritical embrace of AI as naïve boosterism for corporate prerogatives. I decided to look into things myself.

In August 2017, I jumped security and made it into the Singularity University Global Summit at the San Francisco Hilton. It was no easy task: The convention is very well staffed, and black-suited convention employees kept an eye out for convention registration badges at the doorway to every ballroom lecture hall and breakout-session dining room. The enormous badges, proudly emblazoned with the name of each attendee and that of his or her employer, were to be worn from a lanyard printed with the phrase “Be Exponential.” The absence of one around my neck was noted in glances directed at my midsection. I’d already been bounced from the expo hall once, and my ploy to acquire a press pass, recommended by a friend who’d crashed the party the year before, had failed. The Global Summit isn’t a secret, invitation-only convention. But admission is priced north of $2,000, so I couldn’t afford to be exponential. As indicated by the badges I studied as I wandered between sessions, large multinational corporations like Deloitte and Procter & Gamble send mid-level executives to the summit to do reconnaissance on technological innovations in established and emerging markets.

The steep entry fee is is part of the high-gloss veneer of selectivity favored by the organization. Most attendees believe their presence at the summit confers a special stature on their intellect and an illustrious destiny on whatever entrepreneurial endeavor has brought them there. Alumni of Singularity University receive “enhanced” clearance, which provides access to private lunches and sessions where the most elite futurists gather to discuss questions related to the future of human civilization. Attendees were overwhelmingly young, male, and poorly shaven.

The enormous badges, proudly emblazoned with the name of each attendee and that of his or her employer, were to be worn from a lanyard printed with the phrase “Be Exponential.”

I spent the afternoon in Hilton Grand Ballrooms A and B, where plenary talks were held. There I listened as innovators and “disruptors” were invited one after the next to take the stage and share with those assembled whatever TED-talk platitudes they’d rehearsed in hotel bathroom mirrors the night before. As a resident of San Francisco, I was accustomed to their techno-futurist cheerleading and unaffected by the customary flattery of libertarian entrepreneurialism steeped in Objectivist self-regard: a “small group of people,” one speaker informed the audience, was now capable of doing things that no nation-state can do. The obvious inference was that some of those people were in the building.

As the afternoon wore on, I heard about RNA sequencing and was instructed that “as a species we have changed the ways we think about the world around us.” I learned that through interplanetary colonization, explorers might acquire resources from other planets, such as a small quantity of helium 3, which could meet all human energy needs on Earth. I was told that we should make every person “the CEO of his own health.” And I listened as one speaker claimed that there was one thing that no one fights over, and that it was oxygen. What if energy or food, the speaker asked, were to become the “next oxygen?”—the abundance would lead to world peace. I glanced at the Shell employee seated beside me, to see if he, too, had registered the unintended irony. He had not.

The hyperpositivism on display in Kurzweil’s writings was everywhere to be seen at the Singularity University Global Summit. But so were the trappings of American messianic discourse. While seated in those hotel ballrooms, lit by the blue glow of smartphones and the massive projections of each speaker’s PowerPoint presentation, I was able to experience something that years of research on religious enthusiasm could never conjure: I got to feel what it was like to be surrounded by true believers in a cause that was only valued by an in-crowd, an ascendant elect. Circulating among them, I sensed the presence of that spirit that presides whenever so many ardent believers come together in its name. I could feel the souls uplifted. And yet my afternoon ended with a bruising fall from that levitation.

During one of the final keynote addresses, Will Weisman, a high-ranking dignitary from Singularity University, sat to interview a woman about her company, which uses blockchain technology to simplify the process of paying royalties to recording artists. Her clients included the heartthrob singer-songwriter John Legend, who had recently been visiting prisons to perform for the downtrodden and forgotten. “It’s so nice to see the social impact being woven into what you’re doing and the people you’re working with,” Weisman told the blockchain entrepreneur. “And it would be amazing to get some of those folks here and have them drink some of the Singularity Kool- Aid—although I’m sure you’re passing that on!” She assured him that she was.

Needless to say, Weisman was unaware that jokes about drinking the Kool-Aid are supposed to be made by an organization’s detractors—not its adherents or evangelists. Apparently nobody in the audience knew this either: a ripple of polite laughter washed over the auditorium. The tone-deafness of making a Kool-Aid joke in San Francisco was lost on everyone present. Forty years on, the lives of hundreds of activists who died hoping to make the world a better place were trivialized into a meme divorced from its referent and clumsily deployed to wrap up an interview at a corporate conference.

What seldom emerges in conversations with techno-futurists is the realization that there is already enough material abundance on Earth to keep everyone alive and happy.

What seldom emerges in conversations with techno-futurists is the realization that there is already enough material abundance on Earth to keep everyone alive and happy. Only greed comes between basic resources and the hungry, sick, and homeless people who need them. That conversations about limitless abundance would occur in one of the richest cities in human history is hardly surprising. But the fact that more than 7,000 people go to sleep on that city’s pavements each night is a problem that cannot be solved by quantum computing, algorithms, or mobile apps—to say nothing of multinational banks, fancy consulting firms, and fossil-fuel companies. It is an abuse of power that exploits the weak and vulnerable in the interest of making a profit. Correcting such a miscarriage of justice requires not technological disruption, but the compassion of a human heart.

The American messianic impulse is based on a fundamentally irrefutable truth first observed by the Puritans: The injustices of capitalist culture cannot be reformed from within. They are symptoms of the system’s health, not its disease. As Peoples Temple survivor Bryan Kravitz reminded me four decades after Jim Jones issued his last warning about the fascist conspiracy to confine African Americans to concentration camps, private corporations run prisons whose inmates are disproportionately gathered from the sort of poor black and brown communities where Jones concentrated his outreach. Jones’s prophecy was correct, but for one detail: Americans did not require a fascist regime to jail more than 2 million people. It was a conspiracy conducted in the open, with the support of presidents of both major political parties and the broad approval of most American evangelicals.

America’s messianic societies were not perfect: In their quest to tame the vices of hypertrophied American individualism, some of America’s messiahs engaged in forms of repression and control that most would consider authoritarian, if not abusive. Particularly in its final years, Peoples Temple exploited human tendencies for religious zealotry and set them to work toward a violent extremism that previous messianic societies lacked.

By and large, however, American messianic experiments in apostolic socialism appealed to converts’ highest ideals: they stood for equal access to jobs and education, gender parity, racial justice, and more dignified human labor. By joining together in communal bonds of solidarity, adherents often staked everything they had — all their material wealth, as well as their affective energies — on the survival of the group. These sects were strange to outsiders — as strange, perhaps, as the apostolic communes were to the pagans of the Roman Empire. That they appear irrelevant to American historians, aberrant to contemporary evangelicals, and abhorrent to the average consumerist is a signature of the victory capitalism has achieved over the American religious imagination, and a sign of how far American Christians have strayed from the values their Messiah held most dear. ●

This essay is adapted from American Messiahs: False Prophets of a Damned Nation (Liveright, W.W. Norton).

Adam Morris is a writer and literary translator whose work has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, the Believer, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Salon, and elsewhere. He lives in San Francisco. His book American Messiahs: False Prophets of a Damned Nation is available March 26.