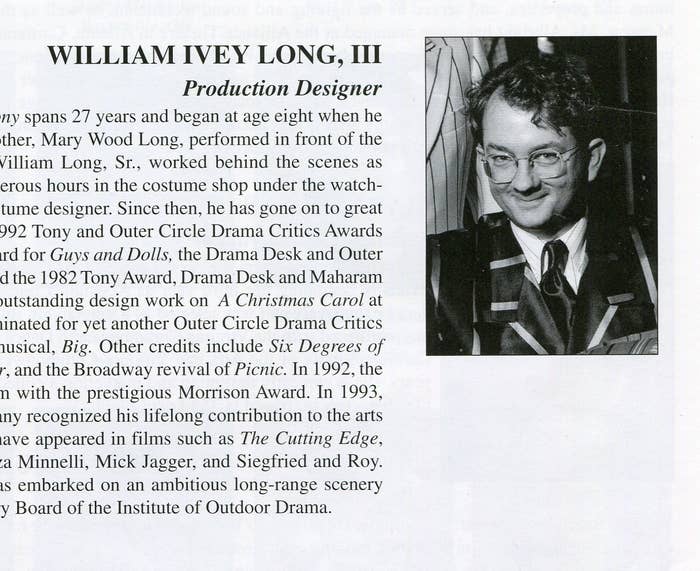

For the last three decades, if you've seen a Broadway show with costumes you adore, chances are high they were designed by William Ivey Long. He's responsible for the jazzy, slinky garments in the long-running revival of Chicago, the Weimar Republic seediness of the garb in the revivals of Cabaret, and the '50s Day-Glo pizzazz of the frocks in Hairspray. He's done gangsters (Guys and Dolls) and princesses (Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella), cartoony comedy (Seussical) and gritty realism (A Streetcar Named Desire), and con artists both earnest (The Music Man) and unscrupulous (The Producers).

He won his first Tony Award for designing the lavish and ribald costumes for the 1982 Best Musical, Nine, when he was just 34; to date, he's been nominated for 15 Tonys and won six. He's done the costumes for the live TV productions of Grease and A Christmas Story. He's been profiled by Vogue and Vanity Fair. And he recently concluded a four-year stint as the chair of the American Theatre Wing, the organization behind the Tonys.

Yet Long's largest legacy in the world of theater isn't in New York, but rather on the northernmost tip of Roanoke Island, a squat, 8-mile strip of land along the Outer Banks of North Carolina. It's where audiences have swarmed to an expansive outdoor theater to watch the same show every summer since 1937: The Lost Colony, a chronicle of the English settlement on Roanoke Island that mysteriously disappeared in the late 16th century. It's where Long's parents first met, while working on the show in the 1940s. It's where, since 1994, Long has overseen the show's production design, supervising dozens of crew members, many still in college and working their first professional job in theater.

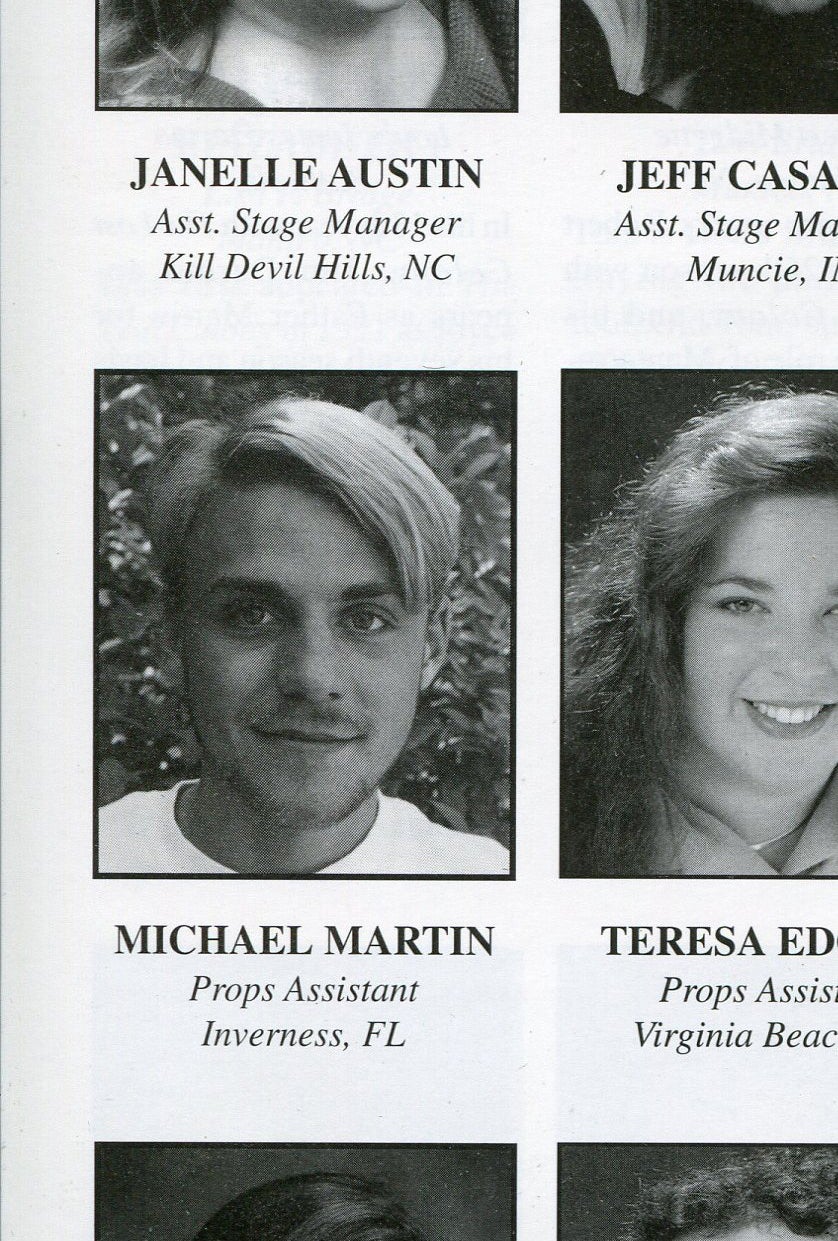

And it's where, in the summer of 1995, Long met one of them: Michael Martin.

The handsome Florida State University undergrad had aspired to life as a stage actor ever since he played the lead in Little Shop of Horrors his junior year of high school. So when he landed a job at The Lost Colony as an actor-technician — basically, a chorus member who also helps out backstage — Martin was thrilled to join a show that many regard as a noteworthy stepping-stone to standing on a Broadway stage, especially with someone of Long's rarefied pedigree involved. Martin was even more ecstatic when, returning for the following summer, he was told that Long had seen something in his artistic abilities, and he was moving to the props department.

That's when everything began to fall apart. In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Martin, now 43, alleges that over the course of the multi-week rehearsal period leading up to the opening of the show in late May 1996, Long relentlessly harassed him verbally and physically, even after Martin had made it clear he had no interest in reciprocating Long's advances. In one particularly striking moment, Martin recalled Long praising his painting work, in front of other members of the crew — to distract them while he slid his hand inside the back of Martin's underwear.

But because Long was such an icon of Broadway theater — by that point, he'd already won his second Tony — Martin believed he had to acquiesce to Long's behavior, or at least endure it. It was common knowledge on The Lost Colony that Long could help launch a person's Broadway career — or kill it.

"If someone had walked onto that show who had even been on Broadway, we would've been like, Royalty is among us," Martin said. "The fact that somebody had Tony Awards meant that you were in the presence of a god. So anything he did was fine. And anything he said was right."

“So anything he did was fine. And anything he said was right.”

Through his lawyer, Long denied ever sexually harassing Martin or touching him inappropriately, and declined requests for an interview. Bill Coleman, the CEO of the Roanoke Island Historical Association — which produces The Lost Colony — told BuzzFeed News in an emailed statement that he started his position in 2012, and as such is "unaware of any of the accusations made by Mr. Martin." He also noted that in Long's current contract with The Lost Colony as production designer, Long now visits the theater "about 5–7 days" to work with "the director and other artistic staff."

Martin's account was corroborated by Martin's parents and a longtime friend, who confirmed to BuzzFeed News that Martin shared his story with them that summer. Embedded in his story are the consequences of the hazy personal boundaries in the world of theater that still persist today, even as the #MeToo movement reshapes the conversation. The effects of crossing those boundaries can of course damage a safe and healthy workplace, but they can also reverberate for years, even decades, later. For Martin, it wasn't that Long killed his career in theater. He didn't need to. He'd already killed Martin's love for it.

During his first summer working on The Lost Colony in 1995, the longest time Martin thinks he spent with Long was for a fitting for the loincloth Martin wore to play one of the Native Americans in the show. Martin isn't even sure if Long was all that aware of him. But Martin certainly had plenty of time to observe Long from afar, and how he would upbraid those working directly with him, sometimes vehemently.

"I thought he was a scary man," said Martin. "I couldn't figure out how somebody who treated people so poorly — who would berate their staff in front of everyone — I couldn't figure out how that person got two Tony Awards."

“I thought he was a scary man.”

This wasn't an uncommon reaction. A friend of Martin's who was present that summer, and said Martin confided in them about Long's inappropriate behavior, told BuzzFeed News they found the verbally contentious atmosphere Long engendered to be "rather abusive." Another participant during the 1996 season said that when he first arrived, veterans of the show warned him about Long. "People said he was temperamental, he was rude, he was bossy, he was mean," said this participant, adding that "you were not to question [Long's] authority" and that "if you didn't do what he wanted, he could wreck your career." And a performer who worked multiple seasons on The Lost Colony put it more bluntly: If he was ever contradicted, Long could be "an evil troll." (All three sources requested anonymity to protect their professional reputations.)

Still, Long was a phenomenal designer, meticulous with the kind of ornate details and painstaking craft that elevated The Lost Colony from a summer stock show to a crown jewel of independent theater in the South, leading it to win a special Tony Honor for Excellence in 2013. Those working on the show faced a troubling, all-too-common bargain: If weathering Long's volatile temper and harsh temperament for a few weeks every summer was the price of his brilliance, then so be it.

Martin's appreciation of this bargain is why, when he landed the props job for the following season in 1996, he thought he understood what working with Long would be like — even after people pulled him aside to remind him that Long could be "difficult."

"I was like, 'I know, I know, I've got this. Don't worry,'" he said.

What Martin wasn't prepared for, however, was how sexually forward Long would be, practically from the start. Twenty-two years later, Martin cannot recall precisely when Long made his first advance that summer — but that's also due to the carefully incremental nature of how those advances occurred, he said.

"It's: hand on the shoulder, hand on the shoulder slips," Martin said, holding his hand in the air on an imaginary person's shoulder, then sliding it onto their upper back. "Then it's: hand on the shoulder slips and stays. Then it's: hand on the shoulder slips and stays and goes to the small of the back. Now touching the very little part of my underwear band. Now there's a finger hooked in there. Now I'm moving the hand."

Martin swept his hand in the air, as if carefully nudging someone else away. "Maybe that happens on Tuesday, and then on Wednesday, the finger goes a little deeper," he continued. "And now I move the hand, or maybe I start moving away, and he changes tactics. Maybe it's a smack on the ass as I'm running by trying to do something else."

“It was always paired with … ‘You really must come for dinner.’ It wasn't like, ‘Oh, if you feel like it.’ It was, ‘You must.’”

Martin said these kinds of encounters with Long would often happen in relative privacy, tucked away in one of the many cramped spaces on The Lost Colony. But not always. "[He had] an ability to kind of creep up behind you, slide his hand down your pants, and then light his face up while he's pointing at something good that you did and making everyone look at that, and then squeeze and dig around in there," he said. "Grabbing your ass and digging in your crack, and it seems like he's fishing for your butthole. And he's smiling and he's pointing at work that you did, and your seven or eight assistants that you have assigned for that day are oohing and aahing. Literally his left hand doesn't know what his right hand is doing."

Throughout the preproduction period, Martin estimated that Long inappropriately touched him about 10 times. He felt trapped by the enormous authority he perceived Long to have not just over him professionally, but over The Lost Colony as a whole. "At one point, [Long] argued with a piece of the direction that the director was giving an actor, and the director let him have his way with how the actor was presenting a line," Martin said. "I've never seen that happen, before or since." The director that year, Fred Chappell, did not respond to multiple requests to comment for this story, and Long, through a lawyer, denied he had the power to overrule the director.

For Martin, the overtures were never just physical, either. "It was trying to cop a feel, and it was always paired with, 'You've gotta come to the hotel for dinner.'" Martin said. "And it was that phraseology: 'You really must come for dinner.' It wasn't like, 'Oh, if you feel like it.' It was, 'You must.'" Long's attorney said that Long "would invite groups of the Lost Colony cast and crew to dinner," but that "Mr. Martin's suggestion of an improper motive behind these group interactions is simply fabricated."

Martin never did attend a dinner with Long.

At some point during rehearsal, Martin noticed that Long had started treating him differently. Long would scold him for missing deadlines in front of his crew. He would reprimand Martin for talking too much, and then snidely add that he liked his work better the day before, when Martin had his shirt off. During one particularly contentious argument over a basket of fake ears of corn, Martin recalled Long snatching a clump of the offending plastic props and throwing it at him in frustration. One person who worked on The Lost Colony during the 1996 season confirmed witnessing Long reprimanding others on the show, and Martin specifically. Two other people who have worked with Long on The Lost Colony said that while they did not have a memory of these specific incidents, they believed Long was capable of this kind of behavior.

Long's attorney said, "Though Mr. Long may be known as somewhat of a taskmaster, and while missing deadlines and talking too much does sound like extremely annoying and problematic behavior which would actually justify a reprimand, Mr. Long would have left the scolding to the Technical Director and would not have scolded Mr. Martin in front of everyone, and certainly not for the purpose of any retaliation as alleged. The allegation that Mr. Long threw props at anyone, much less Mr. Martin, is preposterous."

I asked Martin to put himself as much as he could back in his 21-year-old head, and explain what he thought Long wanted from him. He took a long time to answer.

"Can we say what I hoped he wanted?" he said. "I thought maybe he thought I was smart and realized that I was a good storyteller and a talented actor and really good at production design and set painting and props painting. I thought maybe he was taking a shine to me and was going to mentor me in New York. And I thought maybe…"

He trailed off, his voice catching. "I don't know… Maybe, maybe, maybe there's more to life than just the gross animal instincts. That you see possibility of brilliance and you can foster that."

Martin would catch moments with Long where that possibility seemed within reach, but they were brutally short-lived. He recalled a day when Long visited him at the props shed to tell him the show's director was en route to take a look at a series of wooden toys that Martin and his team had created — gifts the Native children would've given to the colonists' children.

"He took the opportunity to praise me quietly, tell me how I'd gotten the contrast just right, and how I didn't use the high-reflective paint, I used the flat paint, which would pick up the light differently and make it seem like the past," Martin said. "I was swelling up with pride, and the hand came down the waistband again, into my buttcrack." He took a deep breath. "I just turned in that moment, and I looked at him. I don't think I even said anything. In my mind, I decided, If I survive this, I don't know that I'll ever be able to have joy in theater again. I begged him in 10,000 different ways to take me seriously — if not as an artist, at least as a craftsman; or not as a craftsman, at least as an employee."

It's a widespread but still under-discussed part of the #MeToo movement, how this kind of harassment can deeply warp a person's sense of their own value, and inject a persistent, nagging suspicion about why anyone with authority would give them attention and praise. And yet it was hard not to learn some valuable professional lessons from someone as accomplished and knowledgeable as Long. He would hold optional master classes about the craft of theater and buy pizza for everyone after a long day. It was confusing and wearying for Martin, trying to untangle these complicated and contradictory feelings while also putting together a massive theatrical production in the summer heat on a shoestring budget. And it didn't help that while Martin recalled some people on The Lost Colony telling him they "felt bad" for what he was going through, he found that others were much less sympathetic.

"There was a couple of times that I complained at parties," he said. "People were like, 'Oh, the handsome young guy is having a rough time with the older gentleman who thinks he's cute. Oh no! Let me get my violin.'"

“‘That’s how gay people were. There wasn’t a thing called sexual harassment. That was for women.’”

Martin did find more compassion from a friend he confided in through this period, who better grasped the deeply dispiriting understanding Martin was coming to. "It was that first confrontation with the reality that in order to make it in a career, you would have to have your boundaries crossed, or tolerate abuse, or sleep with someone," the friend said. Still, the specific nature of Martin's experience also left his friend unsure about where to place it: "I wondered, Is this the world of the theater? [Or] is this a world of gay men?"

It's a question Martin also had to confront one night when he tried talking with a gay man who was working on the show that season about what was happening with Long. When Martin used the words "sexual harassment," the man shut him down.

"He was like, 'We don't have that, Michael, we don't have that,'" Martin said. It's an attitude he still encounters today when he shares what happened to him that summer: "'Well, Michael, that was just the time. It was how we did things then. That's how gay people were. There wasn't a thing called sexual harassment. That was for women.'"

Martin found this mentality difficult to shake. He was out in high school, and theater had been a sanctuary, a place where he could be as gay as he wanted. But now his sexuality felt like a liability, like it made him open for abuse and left him wondering if older gay men could be genuinely interested in him for other reasons. "The damage that keeps following me is when an older man approaches me and wants something, and I smell that he's LGBTQ, I immediately assume he wants to have sex with me," he said. "I have to see danger around every corner now, and it fucking sucks."

Back in 1996, the final straw for Martin came the day the programs for the show were released. He vividly remembered being told at the outset of the show that his title would be "property master," but when he saw the printed programs, he discovered that his job title was "props assistant." After all his hard work, after stomaching Long's unwanted groping and suffering through his temper, he couldn't even walk away with the credit he felt he'd more than earned. Furious, Martin found Long alone in the costume shop and confronted him.

"I told him to keep his hands off me, or I'd own the place," said Martin — by which he meant he'd sue The Lost Colony for sexual harassment. Martin explained that while he certainly appreciated the opportunity to work with Long and oversee a vital part of the show, the job of keeping track of around 500 props each night was pressure enough without having to contend with Long constantly pushing well past his boundaries.

Long remained pretty much silent throughout, until someone else entered the room. "I said everything I wanted to say, and he was like" — Martin took on an annoyed tone — "'All right. All I heard is that you're stressed out and you have work you're not doing.' That was the validation I got: Get back to work." Long's attorney did not specifically respond to a request for comment about this interaction, but did stress that Long never promoted Martin to property master, and noted that "the [production] designer does not interfere with those selections or hires."

Instead, Martin said he went to see the production stage manager on The Lost Colony, explained everything that was going on with Long, and requested to file a formal complaint. (Martin's friend told BuzzFeed News that Martin had confided the nature of this conversation with them at the time.) He said he was greeted with sympathy and understanding, and told that his pain was seen and his story was believed. With that support, however, came a warning: Long was a powerful man, and if Martin did file a complaint, there was no way to control how others — including Long — would respond.

It was at once realistic and chilling advice, and Martin chose to heed it. "The times were different," he said. "She did exactly what she could at that time … and I respect her for that."

In a letter to BuzzFeed News, Long's attorney said, "We have spoken with the Production Stage Manager at the Lost Colony from the years cited and she has no recollection or record of any complaints against Mr. Long." While the production stage manager for this season did not respond to multiple requests from BuzzFeed News for an interview, a person close to the production stage manager told BuzzFeed News that she has not been contacted by anyone associated with Long or The Lost Colony with regard to this story.

There were other discrepancies in Long's representations to BuzzFeed News concerning this story, as well. On July 25, Long's attorney told BuzzFeed News that "the National Park Service also has complete daily records from the year 1996 at the Lost Colony, and we have requested copies of those records to confirm the absence of any complaint ever made against Mr. Long" and that "the Lost Colony keeps productions records from each day in the theater and is pulling those records to confirm the absence for any such claim." Two days later, Long's attorney said they had successfully obtained "detailed payroll records" from the "National Park Service/Lost Colony office" that proved Martin had not received a promotion to property master.

But the current CEO of The Lost Colony and two officials for the National Park Service told BuzzFeed News that they have no knowledge of any request for documents from the 1995 and 1996 seasons from Long or his attorney. According to the public information officer and the business manager for the Park Service for the Outer Banks, they would not keep payroll records for The Lost Colony participants since they are not employed by the Park Service.

When informed of these discrepancies, Long's attorney said on Aug. 6, "We have been working with the people responsible for compiling the documentation when it was generated at the time, and who also maintain those records now." On Aug. 7, the attorney shared a copy of a payroll document from 1996 for Martin, in which it appears that Martin did receive a raise from his 1995 wages; there is no notation as to Martin's job title. To date, it is the only documentation — beyond a copy of a page from the 1996 program — Long's representatives have sent BuzzFeed News.

Soon after Martin's confrontation with Long, The Lost Colony opened, Long flew back to New York, and Martin settled into the rhythm of the production. But the damage had been done. When his parents came to visit him and see the show, they could already tell that something was different about their son. He had told them excitedly about his new props job at the outset of rehearsal, but as his father, John Martin, told BuzzFeed News, "It seemed like at some point the shine went off the apple."

Martin told his parents about Long's abusive behavior, the inappropriate touching, and the person who had believed his story and warned him about the likely consequences of filing a formal complaint. "She had made a comment to him that she would gladly make his complaint and take it up the ladder, but his career on Broadway might end right there," said John.

It was, of course, upsetting that Long had mistreated their son. "I said, 'Where is this guy?'" John Martin said of Long. "'I want to talk to him nose-to-nose.' I probably would have beat the crap out of him, and you can put that on the record, I don't care. I'll give him my address. He can come and visit me."

“I probably would have beat the crap out of him, and you can put that on the record, I don’t care.”

What was more distressing, however, is what happened after the summer ended, and Martin returned to FSU. An academic achiever his whole life, Martin stopped going to classes. He became despondent and depressed. And he left FSU without completing his senior year.

"This was a kid with endless energy," said John Martin. "He was the captain of the swim team. He was the class president. He was not only in the school's plays, he was the star in the community theater."

"He had a portfolio [for acting] when he was 5!" said his mother, Donna Martin. "He used to beg me to take him on commercial auditions. This was a passion. … It was really disappointing to see him lose his spark."

Long returned to The Lost Colony one more time that summer to check up on the production, and he and Martin had another confrontation, this time about a one-man musical revue Martin had mounted during his spare time that featured a song called "The Casting Couch" — a not-exactly-veiled reference to his experiences with Long.

"I said something like, 'You know what, I gave up a summer onstage, and I did it because you are brilliant and because everybody says you're this brilliant guy,'" Martin said. "'And as soon as you realized you weren't getting what you wanted out of me, you stopped mentoring me, you stopped paying any attention to me, and you started just being a dick.'"

Long's response surprised Martin. "He was like, 'Writers are the true artists of the theater,'" Martin said.

It's something that has stayed with Martin to this day. "Because processing this thing has been super complicated, and has taken my entire life, I must find some sort of good in the bad things that happen to me," he said. "It clicked with me right then. He's right. Writers are the true artists, and not only are they the true artists, they get to decide what history is — they get to decide the stories." Long's attorney said that while Long has said "Writers are the true artists of the theater" many times, Long denied ever saying it directly to Martin.

Martin moved to New York and fell into the improv and stand-up comedy scene, where he could write his own material and control his own story. In 2009, he started writing a blog, which he maintains to this day, that earned him a modest but noticeable bloom of celebrity when he started posting photos of himself baking pies while wearing an apron — and nothing else. Even Long caught wind of it.

“I must find some sort of good in the bad things that happen to me.”

"He approached me in a Barnes & Noble, and was like, 'Look at this. Our young writer's finally blossomed. And all you had to do was take your pants off.'" Martin rolled his eyes. "I was like, 'Well, as you know, William, I am in control of my body, and I control who gets to see it, and when, and how.' … He said something about a porn star that is a concert pianist as well. And that was it. He just, like, wandered off." Long's lawyer said these claims were "accurate, though misconstrued." The lawyer conveyed that Long's recollection is receiving an invitation to an event 10 years ago, and he attended to "support all of his Lost Colony alumni." At that event, he said, "Mr. Martin did draw attention to his own attempts to make a successful career by appearing naked on his blog (as he still does), and Mr. Long did comment on that fact, drawing comparisons to the Naked Chef. Such a comparison was made, in jest, to an adult."

Today, Martin lives in Los Angeles and has cobbled together a tapestry of disparate employment — from tending bar to IT consulting to social work with young kids — when he's not working on his own creative endeavors. But what happened to him on The Lost Colony still lingers.

"If it bothers me so much that somebody 20 years ago took advantage of his position and I'm losing sleep, that is still unfair," he said. "That is still them having power over me, and I refuse it." Emboldened by the #MeToo movement, Martin decided to talk publicly about his experience on The Lost Colony for the first time. He posted on Facebook about his experience with Long in May, and then ultimately connected with BuzzFeed News. "I thought to myself, Good lord, can we actually speak truth to power? Because if we can, I've got a lot of truth, and there's a lot of power I resent."

He thinks about the profusion of enthusiastic young people who funnel through The Lost Colony — and Long's purview — every summer, including this one. He thinks about how what they do and how they're treated there will shape how they see themselves and the world. And he thinks about how his experience there led him to cut short a life in the theater before he'd even really started it.

"I'm very careful with what I say to young people because I don't want to do what he did to them," Martin said. "I don't want the world for them that was the world I had. I want better. I want better for us." •