When Jennifer Fox was 13 years old, she entered into a sexual relationship with her running coach. He was 40. They were in love.

At least, that was the story Fox told herself in the years following the end of her time with her coach. It was so central to her life that as she began her career as a documentary filmmaker in her twenties, Fox began working on a screenplay treatment about her experience, to turn it into a movie. Something about her approach never felt right, so she set it aside. But the drive to grapple with her experience was always there, like an itch she couldn't quite scratch.

It was only when Fox was in her mid-forties, as she began working on a film that involved other women talking about their own stories of sexual abuse, that she suddenly saw her relationship with her coach through a radically different lens.

"It was just, like, this snap," Fox told BuzzFeed News in an interview at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival. "I was like, 'Oh my god, that sounds like my story. Oh my god, it's sexual abuse.'"

Fox's understanding of what happened to her might have stopped there, as she fell into an all too familiar role of a victim of child sexual abuse. Instead, Fox kept asking herself, over and over: Why hadn't she seen the relationship as abuse before? Why had she been telling herself this other story about her experience for so many years?

The ultimate answer to those questions is The Tale. Fox's searing autobiographical account of her experience debuted to a stunned and rhapsodic reception at Sundance in January, and premieres on HBO on May 26, as an uncanny (and serendipitous) addition to the country's ongoing reckoning with abusive sexual behavior in the wake of the #MeToo movement. In the film, Laura Dern plays Jenny, a lightly fictionalized version of Fox, who begins a journey of rediscovering not only how her coach — called Bill in the film and played in flashback by Jason Ritter — coaxed her into their relationship, but how her memories of that time shaped her understanding of it, and of herself.

“I don’t feel like a victim, and I’m not interested in telling that story.”

For Fox, that experience, while unmistakably scarring, was far from a tidy narrative of a sexual predator and his unwitting prey. "I don't feel like a victim, and I'm not interested in telling that story," she said. "I wanted to tell what this child created in me. She created the hero I would become just by the way she told herself what happened. That's a really mind-blowing thing."

In order to capture that kind of nuance, and so that viewers could truly understand the knotted psychology that led a 13-year-old girl to believe she was in an equal, loving relationship with an adult man, Fox understood instinctively that her approach had to be unsparing. "Sexual abuse is often just this misty [thing]," she said. "You know, they walk into a room and close the door, and you hear sounds, or it's a hand on a mouth."

Instead, Fox was determined to painstakingly recreate her experience, from Jenny's first "dates" with Bill as he groomed her with praise and attention, to the deeply upsetting reality of their sexual experiences together. "There are all these steps that are very brutal, but that's the way sexual abuse happens, in little tiny increments," she said. "It's why I can never call it rape. As far as I was concerned, even though I was a minor and couldn't technically consent, I thought I was consenting. I'm consenting here. I'm consenting there. I wanted an audience to go through that. … It was really important that we don't shy away from the truth in all its discomfort."

Having the courage of those convictions, however, presented Fox and her collaborators with a hair-raising challenge: finding a child actor capable of embodying the complex emotions coursing through the story, and then figuring out how to shoot some of the most squirm-inducing scenes between a child and an adult without traumatizing either of them.

The easiest solution to finding an actor to play the young Jenny would normally be simply to cast someone who was 18 but looked much younger. But when Fox was 13, she said, "I looked like a 9-year-old boy. … I was as far away from Lolita as possible."

Fox and her casting director kept looking younger and younger, but "even the 13-year-olds in America just weren't that immature," she said. At one point, the filmmaker thought she might have found the right actor in the young French-Canadian actor Sophie Nélisse, who had just made a powerful impression as the star of 2013's The Book Thief. But securing financing for the film took so long that by the time production was ready to start in 2015, Sophie had already aged out of the role.

Which was just as well, since, according to Sophie’s mother Pauline Belhumeur, her daughter wasn't all that keen on the part to begin with. But Fox was desperate, and she remembered that Sophie's 11-year-old sister Isabelle was also acting (she'd been in the 2013 horror film Mama). So she called Belhumeur directly and asked if Isabelle might consider the role.

Rather than warn Isabelle about The Tale's story, Belhumeur chose to hand the script to her with zero preamble — she didn't even want her to know Sophie had also been approached about the role. Instead, she felt her daughter should be able to have her own reaction to the material, and not feel any pressure either way. "I knew she was quite mature for her age," Belhumeur said of Isabelle. "Because [the film's story] is true, because it needs to be talked about, that's why I let her even read it in the first place. I knew she could take it, because I knew her."

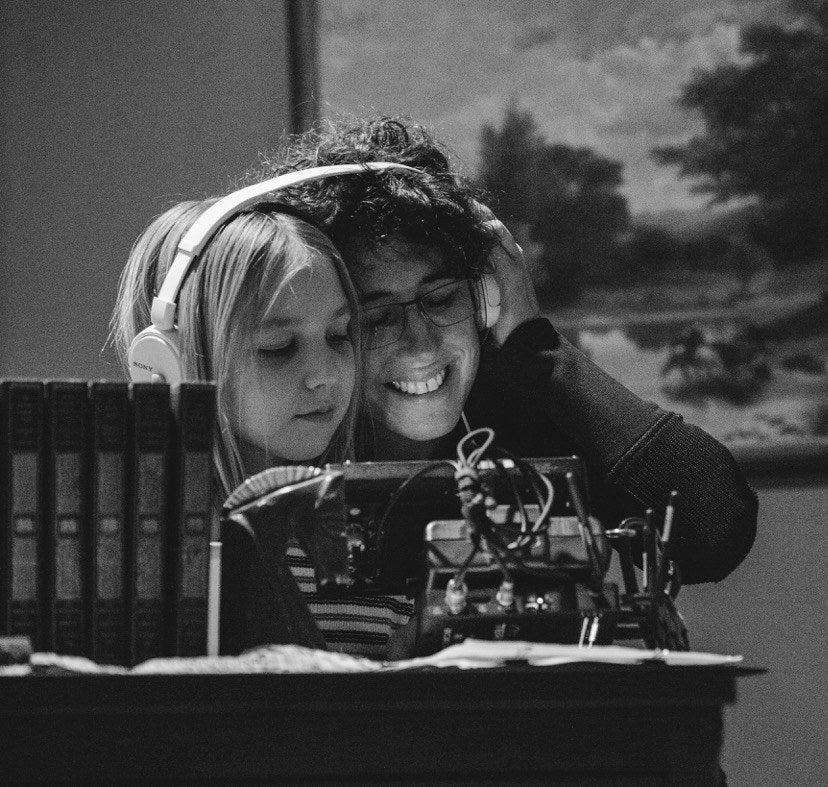

After reading the script, the younger Nélisse got on a Skype call with Fox to talk about it, and immediately, Fox understood that she already had a keen grasp of the material. "She had a million questions for me," said Fox. "'Is this really true? What was the real Bill like? Why did you do it?' Like, she really wanted to know about me, the truth, why I wanted to tell the story. She was 11. It gives me goosebumps now."

More pointedly, Nélisse also had several questions about Jenny's sex scenes with Bill. "I didn't really know how it was going to be shot," Nélisse told BuzzFeed News. "I'd never, like, done things that were like this before."

"I would never allow my kids, one, to show their own body, or two, to be touched," added Belhumeur. "If they had wanted to film her real [naked] back, or her to do these things with him, obviously I would have refused them."

“I was very clear there was no way Isabelle was going to be traumatized by this event.”

Fox assured Nélisse and Belhumeur that there wouldn't be any nudity of Jenny whatsoever in the film save for the character's naked back, and that scene, as well as any scenes of intimate physical contact between Jenny and Bill, would be shot with a body double. "Although we hadn't figured out exactly how [yet], that's what we went through," said Fox. "I was very clear there was no way Isabelle was going to be traumatized by this event. We were going to protect her in every way we knew how."

Those kinds of safeguards are far from guaranteed for child actors; Hollywood still relies heavily on parents and guardians to be the fiercest — and, too often, the only — advocates for their children’s overall welfare. And indeed, Belhumeur’s concerted involvement in how her daughter would be treated on The Tale was born from years of experience of wading through the kinds of offers that can come to a young, in-demand female actor. She recalled that after Sophie decided she wanted to take on more intense roles (like Leonardo DiCaprio in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape), “people started offering her things about rape.”

For The Tale, however, Belhumeur was confident in both the righteousness of what Fox was attempting, and that Isabelle was capable of handling what would be asked of her. But she also understood that others could question her judgment. “I know people might criticize — you know, like, ‘Why did you let your kid do this?’ But when you know how it's done, there was really nothing wrong in the doing it itself,” she said. “I've had discussions with different directors on other movies for both my girls, and sometimes — a lot of times — you don't need to see those graphic scenes. In this one, no matter how raw it is, I think they were very important.”

Before he signed on to play Bill, Jason Ritter also wanted to know exactly how Fox intended to shoot Bill's scenes with Jenny "so that we weren't traumatizing an entire new person in order to tell a story," he said. "Even though it's all acting, I feel like it's dangerous territory."

That feeling only became more acute as Ritter began researching his role, largely drawing from correspondence Fox had kept from the real Bill, as well as the memoir Tiger, Tiger by Margaux Fragoso, which chronicled the author's harrowing and complicated sexual relationship as a child with a much older man.

"It was disturbing," Ritter said with a deep sigh. "One of the things that was so upsetting about it was how normal it sounded. They appear to care about the person. They are able to give the person some kind of sense of themselves, making them feel special."

“Jennifer kept on telling me over and over again, ‘He believes this.’”

The maxim that actors cannot judge the characters they're playing was also constantly front of mind for Ritter, in part because Fox wouldn't let him forget it. "Jennifer kept on telling me over and over again, 'He believes this,'" said Ritter. "Throughout the entire experience, when I would have a question, like, 'Oh gosh, this element is so intense, are you sure?' She'd go, 'Yes. That's what happened — to me. So this is the story that we're telling.' … I had to continuously put aside my own feelings."

That imperative was especially crucial during Ritter's sexual scenes with Nélisse's body double (who has asked to remain unidentified). "I was able to just try to feel this affection and love towards her, knowing that when it cuts back, and you see Isabelle's face, that's where the horror comes in — not in me mustache-twirling and saying it in a creepy, horrible way," he said. "It makes you even more angry, because you see how this child was able to compartmentalize this, and 30 years later would be referring to it as a relationship that she had, where they were in love, and it was special."

For Nélisse's side of these scenes, Fox and her team established a system aimed at sequestering the actor from any of the harsh details of what was actually happening. First, Fox rehearsed with Nélisse in her hotel, running through generic reactions to what Jenny might be experiencing in the moment, but devoid of context.

"Jennifer said, like, 'Do, like, if a bee stings you, or if you're running like a dog,' stuff like that," said Nélisse. "That helped a lot."

Then for the actual shoot, Nélisse stood against a vertical bed, with the camera roughly six feet away and shooting with a tight zoom lens just over Ritter's shoulder as he spoke sanitized, alternate dialogue.

"She didn't hear the scene," said Belhumeur. "She had read them once in the script, but she never heard them on set. She wasn't even allowed to listen in."

Belhumeur was present for all of it, along with a representative from the actors union SAG-AFTRA, a psychiatrist, and Nélisse's on-set tutor. Once her sides had been shot, Nélisse left the set, and then the crew would shoot Ritter's coverage with the body double — often days later.

"I was really heartened by how protective everybody was on the set with Isabelle," said Ritter. "Sometimes you see that on a set, where someone's uncomfortable, and the director or someone is going, 'Oh, just go with it.' There was none of that at all on this set."

Nélisse said she never really talked with the psychiatrist except to go over the legal restrictions for any physical contact between her and Ritter. But if anything, she felt a bit annoyed by all the precautions in place for her. "It felt really kind of overprotective," she said. "I was like, 'It's really OK. There's no need to have like 100 people on set.' But it was fine."

There was only one scene in The Tale in which Ritter had any appreciable physical contact with Nélisse, a brief sequence where they hold hands while they wait in line to see a movie.

"That was more unsettling than I had anticipated," said Ritter. "I've held kids' hands before. It's felt always totally normal and protective and great. To do these scenes knowing what I knew, and holding Isabelle’s hand, all of a sudden, it felt tainted for me. It's another disturbing visual: You see this man holding this girl's hand, and you assume, daughter, niece, you know? No one looks twice." Ritter sighed. "Isabelle was fine with it. She just grabbed my hand like everything was normal. I was the one who was like, I have to put this aside."

While the production went out of its way to insulate Nélisse, there were no such emotional safeguards for the adult actors, who had to improvise their own coping methods. Beyond generally acting as goofy and easygoing as possible, Ritter made sure to spend a great deal of time with Nélisse and her mother off the set, visiting a local amusement park and science museum, along with his costar Elizabeth Debicki, who plays Jenny’s riding instructor and the person who first introduced her to Bill.

“I needed to make sure that, for my own sake, Isabelle knew me and trusted me.”

"It was equally important for me, I felt like, as it was for Isabelle and her mom," said Ritter. "I needed to make sure that, for my own sake, Isabelle knew me and trusted me."

For Nélisse's part, Ritter's efforts certainly worked. "Even though Jason is like 30 years older than me, or something like that, we were really close," she said. "He's such an amazing person. … He's the kind of guy that would never hurt anybody."

But as much as Ritter strived to remain lighthearted during the shoot, "there was a moment where my little survival mechanisms all broke down at the same moment," he said. "We were running lines, and I just looked at her face, and I just saw that she had grown to trust me, and we liked each other. The idea that such a beautiful thing about children, that they can inherently trust people…" He paused, and took in a deep breath. "The idea that someone could exploit that — I stopped in the middle of running lines. I was just like, 'I just have to sit down for a minute.' And it all just kind of poured out of me for 10 minutes."

"He had huge tears," Nélisse said. "He was like, 'How can a person do that?'"

According to Fox, it wasn't the only time Ritter broke down, either. "He cried many times, actually, when he was even shooting with the body double, when he had to really face what he was doing," she said quietly. "He's a very special person."

Fox completed The Tale by August 2017, two months before the stories containing multiple allegations of sexual harassment and assault against indie film titan Harvey Weinstein plunged the entertainment industry and the country at large into the most extraordinary conversation about sexual misconduct and abuse in a generation. The timing could not have been more fortuitous for Fox's film, and no one recognized that more acutely than she did.

"I absolutely feel if we had been at Sundance a year ago, I don't think people would have had the stomach for it," she said. "I think it's only because of this conversation that this now can be something that people can actually accept, that this is not only true but important to look at. If it had been last year, people would have just said, 'I can't take it. It's too much. Why did she do it? Let's just turn away.'"

This is not to say that The Tale still wasn't regarded as one of the most intense films ever to play at the festival — just that it also benefited from debuting in a particularly intense moment in history. "When I first read the script, it felt like a sledgehammer of information hitting me in the head," said Ritter with a mordant chuckle. "But you had already been punched in the face several times by the point you saw the movie, so a sledgehammer didn't feel as shocking. There was a level of talking about trauma in a way that it's very hard to talk about, but the more you talk about it, the easier it is.”

“We have to start talking about this honestly,” Fox said. She recalled the moment, just days after The Tale premiered at Sundance, when an old friend stopped her on the street and proceeded to share a story about abuse that she’d said she hadn’t told anyone, including her family. It confirmed for Fox her greatest hope for The Tale, that it could both help its audience understand the vast well of unspoken sexual mistreatment, exploitation, and abuse that has only started bubbling to the surface, and provide those with their own untidy story to tell with a new model for how to start sharing it with their friends and family.

Or a total stranger. "There was this actress that came up to me, and she's like, 'Hi. I just wanted to tell you that I'm really impressed with your performance, and that's exactly how it happened to me. I'm really happy that you were brave to do this movie,'" said Nélisse. "It made me feel so, so good." ●