In many ways, the new feature film Pride — which is now in theaters in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco — shares its cinematic DNA with several other beloved films from the U.K. Like Billy Elliot, it's set during the fiercely contested, year-long miners strike in the mid-1980s that, for many, came to define Margaret Thatcher's tenure as prime minister. Like The Full Monty, it's about regular working-class folk banding together to buck convention and make the best of a bad situation. And like Kinky Boots, it's about the surprising results when those working-class folk find themselves relying on LGBT outsiders who can help them realize their dream.

According to screenwriter Stephen Beresford, however, there is an entirely different sort of British film that was a common reference for the filmmakers while they were making Pride: "We used to say it's the lesbian and gay Lawrence of Arabia," Beresford told BuzzFeed News during the Toronto International Film Festival earlier this month. The reason, he said, was simple: "Endless characters."

Based on a true story about a group of British LGBT activists who formed Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (or LGSM) and came to the aid of a small Welsh mining town, Pride does indeed stand as one of the few major motion pictures to be populated with more than just a small handful of LGBT characters (if any at all). All told, in fact, Beresford said there are a whopping 38 LGBT speaking roles in the film, including newcomer Ben Schnetzer (The Book Thief) as crusading activist Mark Ashton; Dominic West (The Wire) as hard living actor Jonathan Blake; Andrew Scott (Sherlock) as Jonathan's unobtrusive partner Gethin (who also owns the bookshop that serves as the group's HQ); Faye Marsay (The White Queen) as the up-for-anything Steph, one of the only lesbian members of LGSM; Joseph Gilgun (Lockout) as Mark Ashton's right-hand man Mike Jackson; and George MacKay (Defiance) as Joe, a university student inching his way out of the closet, who often serves as the audience's entry point into the larger narrative.

With so many lesbian and gay characters packed into a true story, one that was unknown to virtually every cast and crew member before they started making it, the importance of authentically capturing their queer identities became of paramount concern to the filmmaking team — and that much more complicated too.

"I was anxious about making the film, doing it justice," said director Matthew Warchus, best known for his Broadway stage productions of God of Carnage and Matilda. "As a straight man, it's not as though I can walk in to a gay club in London now and understand everything about gay politics in the 1980s — such a different world. And yet I didn't want to get anything wrong. I didn't want to make generalizations and rely on clichés at all."

Tipping into camp caricature was all too easy with a story rife with the differences between gay and straight people. "I can imagine a version of this [movie] that's like The Birdcage," said producer David Livingstone. "We always kept talking about how camp is not [automatically] gay. Camp has always had a place in the cinema, with In & Out and The Birdcage. You can do that version of it, but we were keen not to make that film. We wanted to make a film about real people."

For Warchus, however, making Pride into a fabulous campfest was a nonstarter. "I can't do camp," he said, appearing almost sheepish about his deficiency. But he also noted that because of all the particular details about the true story behind LGSM that Beresford learned in his research, the film would be better for embracing a more grounded sense of realism. "Interestingly, it's a film that requires almost no camp. That's one of the sort of noticeable things about it, I think. It's more specific than that."

Instead, to capture that sense of specificity, Warchus turned to his gay screenwriter to, he said, "police my gay and lesbian judgment."

Beresford smiled when recalling how this would work. "I was beside [Matthew] all day, every day on set," he said. "He'd go, 'Is that a bit too gay' or 'is that not gay enough' or 'should there be more?' That was actually essential." Beresford also recalled at least one instance where the crew members in charge of background extras were asked to fill a gay bar. "We'd arrive on set, and they'd have 100 extras for the scene, 50 men and 50 women, and I'd say, '50 men and 50 women in a bar is a straight bar. We need to lose 46 women or 46 men.' It just didn't even occur to them."

One of the biggest concerns for Beresford, however, had to do with how the LGBT characters were portrayed on screen, period. "I think most gay films are about sex, or romance, and focus on that entirely," he said. "That was the first thing I wanted to avoid. … I feel quite strongly that for a lot of young LGBT people, the only version of themselves that they see reflected back is a sexual one, and there is a sense in which we're saying to young people as they come out, 'Your only value, really, is sexual.' Certainly in the U.K. that's the case — I don't know [about] the U.S. It troubles me, because if you don't have a six-pack when you're 23, or if you're not a hot lesbian, you're [thinking], 'What am I? What's my worth? How am I valued?'"

Beresford was quick to note that Pride's LGBT characters all do have an inherent sexuality, and express it naturally over the course of the film (small SPOILERS follow). One character sneaks off to snog with another man during an LGSM fundraiser, and another finds herself suddenly making out with a woman from the Welsh mining town. (The threat of AIDS also hangs over the film, but doesn't dominate the story.) Beresford was equally clear, however, that it was important that their sexuality not be the only defining issue for the characters, and that, perhaps, it is one of the only things they have in common. "They're very different kinds of gay people," he said. "There's the younger people and their antipathy toward the older gay lib people. They sort of moan that gay people should be less flamboyant in order to fit in. All of that stuff is still alive in gay culture [now]."

And Beresford wasn't alone in that feeling, either. "I don't really see it even as playing a gay role, because this is a guy who's struggling with his nationality — he's not struggling with his sexuality," said Scott, who has himself spoken candidly (if not all that frequently) about being a gay actor. "When you've got 12 leading characters who are all gay, you can't just be playing a 'gay role,' because that's impossible. … I love the idea that these characters aren't sexualized, that they're gay people, but that the aspects of their personalities aren't to do with their sexuality, they're to do with their compassion and their solidarity, and their heroism."

At the same time, however, Beresford also said he wanted to be sure the LGBT characters captured "something queer … that otherness." To that end, Beresford also took some of the actors out to gay clubs at night, and Marcus asked him give an illustrated lecture to the cast on the LGBT rights movement in the 1980s in the U.K. "So everybody had the key understanding of what it was like at the time, and what had been happening in the decades leading up to it," said Marcus. "That was an eye-opener."

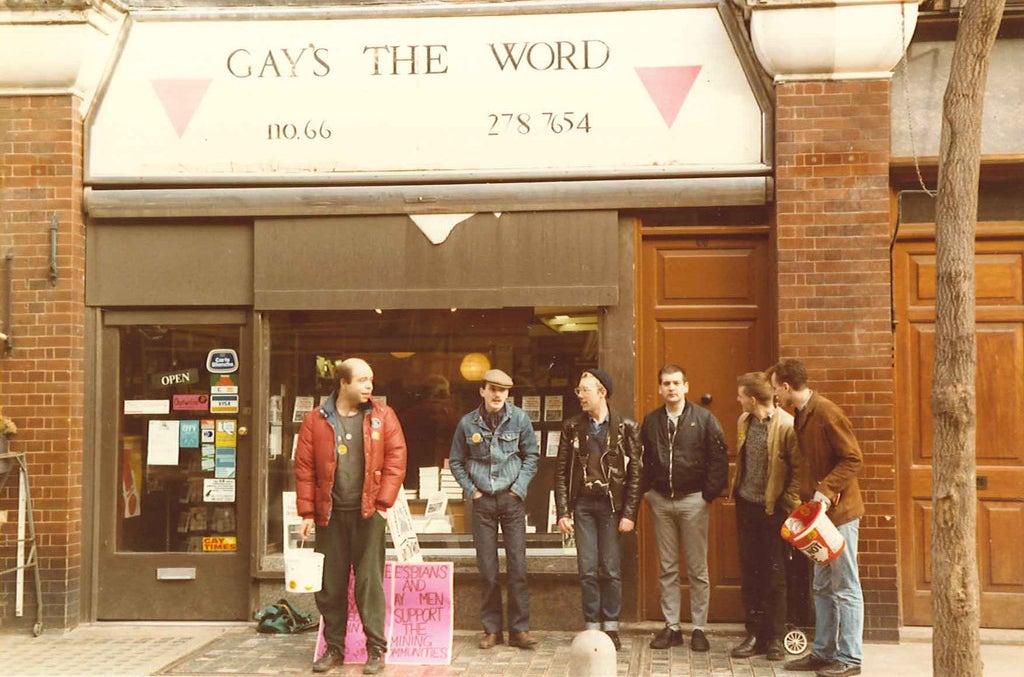

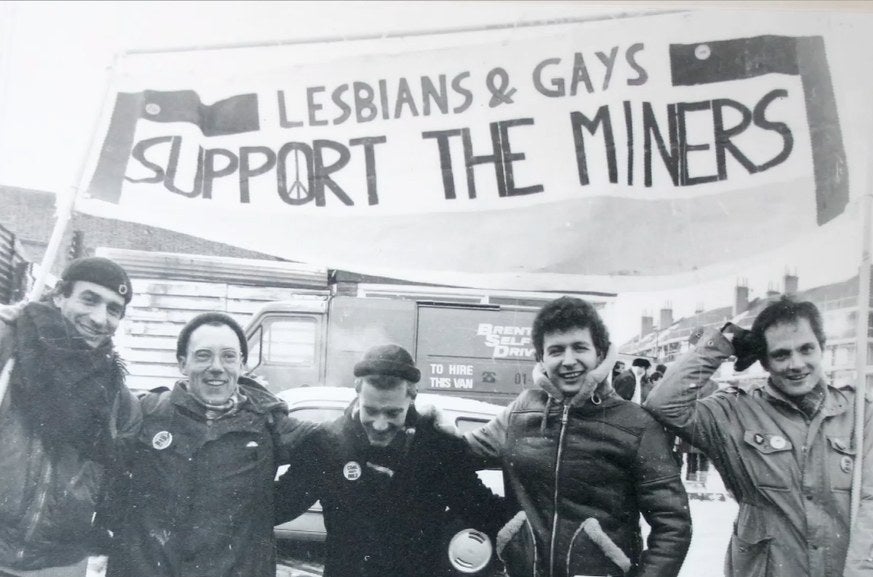

Archival photos of the real LGSM during the 1984–85 miners strike in the U.K.

Of course, had the cast consisted mostly of gay actors, some of this LGBT education may not have been as necessary — a concern that occurred to Warchus during the casting process. "In my state of worrying about everything and getting it right," he said, "I did say at one point when four or five people had been cast, 'You know, I don't think we've got any actual gay people in the movie yet,' to [David] and Stephen. And they said, 'Yeah, I don't think we've got any actual miners, either.'"

Indeed, everyone BuzzFeed News spoke with from the film ultimately felt that it was not necessary for LGBT actors to play these LGBT roles. "The nature of being an actor is you should be able to act, and you should be able to pretend to be things that you're not," said Livingstone. "The difficulty you have is, you can't say, 'OK, let's just look up all the gay actors, and let's choose amongst them.' Because the truth is 9 out of 10 times they're not available, or they don't want to do it, or they don't want to be typecast. You can't start with that premise."

Scott was even more direct. "You don't see George Clooney and Sandra Bullock in Gravity and think, Oh my god, are they actually in space?" he said. "The only question should be, to my mind, is whether the person is proficient at playing the part. And when somebody is good at playing the part, it doesn't matter."

For as much as the filmmakers strove to create an authentic re-creation of gay London in the 1980s — not to mention a working class Welsh mining town — the irony is that the drive for credibility was ultimately in the service of both queer and straight audiences connecting with the commonalities between the characters, and not their differences.

"The film's saying, 'You don't have to be gay to care about gay rights, you don't have to be a woman to care about women's rights, you don't have to be an ethnic minority to care about racial equality,'" said Warchus. "I find reassurance in the fact that we were a team of people who were gathered there to tell a story, and the story would do the work."