“I was so happy he died.”

Ten years after Michael Jackson’s death, it’s bracing to hear those words spoken aloud about the pop music megastar — let alone hear an audience burst into applause in response.

On a chilly afternoon in New York City last Wednesday, a crowd of roughly 100 people spent the afternoon at TheTimesCenter watching an advance screening of Leaving Neverland, the HBO documentary alleging that Jackson maintained intimate sexual relationships with two underage boys — James Safechuck and Wade Robson — over multiple years.

In the film’s fourth and final hour, when Safechuck’s mother shared her glee upon learning Jackson had died — “Oh thank god, he can’t hurt any more children!” — the audience began clapping with sudden, almost angry passion.

The reaction likely was because the audience was filled with child sexual abuse survivors and their supporters.

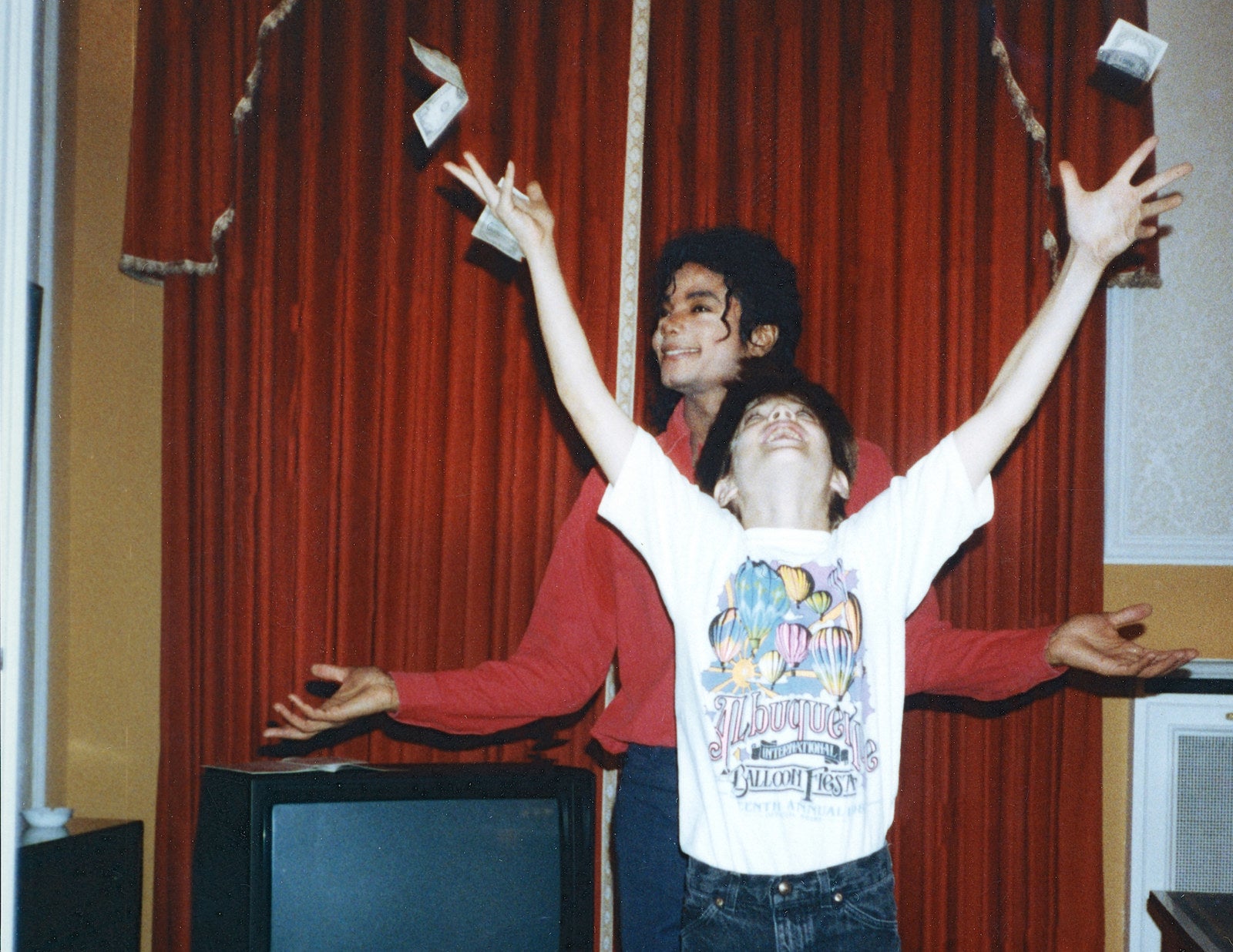

They watched Safechuck and Robson describe in painstaking and painful detail the sex acts they say Jackson made them perform with him for years, Safechuck starting when he was 10, Robson when he was 7. They watched Safechuck, Robson, and their respective mothers, Stephanie and Joy, talk about how Jackson groomed them with lavish attention, gifts, and the otherworldly perks of his stardom before, during, and even after the men say they were having sex with the pop star.

They watched Safechuck and Robson explain why they lied to defend Jackson as children during his 1993 sexual abuse scandal — and Robson explain why he defended Jackson as an adult, this time on the witness stand, during the singer’s 2005 trial for allegedly sexually abusing a 13-year-old boy. And they watched Safechuck and Robson discuss how becoming fathers plunged them into a chasm of depression as they began to recognize that what they say happened to them with Jackson was, in fact, abuse.

Once the film concluded, the audience burst into applause again, this time for Safechuck, Robson, and Leaving Neverland director Dan Reed as they stepped to the stage to talk about the film with Oprah Winfrey, perhaps the most famous child sexual abuse survivor in the world.

It was an unmistakably powerful moment for Safechuck and Robson. It was also unlike anything either man had anticipated.

“I tried to set realistic expectations, which was everybody’s going to hate us, and no one’s going to believe us,” Safechuck told BuzzFeed News in an interview with Robson at HBO’s New York City headquarters.

“If history was any indication, we would just be mowed down.”

Both men signed on to the film months before the #MeToo movement galvanized a national reckoning over sexual abuse and assault; instead, their frame of reference was only the incredulity and hatred they had received after suing the Jackson estate in 2013 and 2014, claiming it was complicit in the alleged abuse.

“That was the climate we were facing when we were saying, ‘Yeah, let’s do this,’” Safechuck said. “If history was any indication, we would just be mowed down.”

Robson said he saw Reed’s film as an opportunity to speak “at length and in detail” about his experience with Jackson in a way his lawsuits — which are pending appeal — have not. But even well after saying yes to the film, Robson’s wife, Amanda, who is also interviewed in the film, wasn’t certain why they were doing it.

“She kept questioning, like, ‘We’re putting ourselves in such a vulnerable position. The length that we’re going to go into every aspect of our lives — are we sure we’re doing the right thing?’” Robson said.

Two years after their first interviews with Reed — and despite a renewed uproar of incredulity and hatred from Jackson’s fans and vociferous denials from Jackson’s family — Robson, now 36, and Safechuck, 40, agree that doing Leaving Neverland was worth it. In an emotional interview with BuzzFeed News, both men relayed the profound effect the experience of making the film had on them, and how it helped illuminate their perspective on Jackson, and themselves.

When Reed first learned of Robson’s and Safechuck’s lawsuits against the Jackson estate, he was in the middle of researching the broad subject area of the Jackson child abuse allegations, he said in an interview at the Sundance Film Festival in January, where Leaving Neverland premiered.

“I had no idea what was the truth,” he said. “It wasn’t a story that I’d followed.”

Reed had built his filmmaking career documenting war zones and terrorist attacks — his most recent was the 2016 HBO documentary Three Days of Terror: The Charlie Hebdo Attacks — and he professed he wasn’t much interested in the worlds of celebrity or entertainment. But he started looking into the Jackson case on the suggestion of an executive at Channel 4 in the UK, and he was intrigued by the fact that two adult men had claimed Jackson abused them as children — before that, all of Jackson’s accusers were still children when they’d made their allegations against the star.

After first contacting Safechuck’s and Robson’s lawyers in September 2016, Reed finally met with the men in person in February 2017, first with Robson in Hawaii, and then with Safechuck in Los Angeles. He brought his filmmaking equipment with him, and within days, both men were talking with Reed on camera.

“Dan has a nice way of making you feel comfortable,” Safechuck said with a smile. “He’s been doing this for a long time, so I’m sure he has his ways. But it’s a leap of faith. He made it very clear, ‘You will have no control over anything.’ I just have to sort of spill my guts and trust that he’ll treat it with respect. That was a big decision.”

“Really, we formed a relationship of trust,” Reed said. “You have to trust me not to misrepresent what you’re saying, and I need you to tell me your story in the simplest and most direct terms possible.”

Keeping Safechuck’s and Robson’s narratives straightforward was particularly crucial to Reed’s approach. He had read their accounts of Jackson’s abuse in their legal filings, but he knew he needed both men to speak only to what they knew and experienced at the time they experienced it, rather than through the lens of what they understood about those experiences now as adults. All told, Robson’s interview took three days; Safechuck’s took two.

“You need to approach it with more or less a blank slate and just listen,” Reed said. “If you decide what the story was before you began, you’re going to try to confirm your own biases, and you’re going to try to hear things or make people say things that perhaps aren’t the right thing or aren’t what they really wanted to say. I don’t believe in doing that at all.”

Robson found that process liberating.

“There was no heads-up of, like, how the interview process was going to go. I don’t think Dan necessarily knew either. So it was kind of just jumping in and figuring it out as we went along, you know?” he said. “Doing that enabled me to re-experience it all as I told it to him, which ended up being just a whole new level of release for me. I had never quite experienced that. I’d been in a lot of therapy and I’d talked about all those things before, but not in order.”

In person, Robson is something of an interviewer’s dream: He’s measured, direct, and friendly without evincing a need to be liked. He’s also been famous in his own right for nearly 20 years, after his career as a choreographer exploded working with NSYNC and Britney Spears, so he understands what it means to talk about himself on camera.

“Because I lived through the abuse, it seems normal.”

Safechuck does not. After his time in Jackson’s orbit ended, his adult life drifted back into the unobserved pace of a private citizen. While his soft-spoken nature remains quite unguarded — his face has the kind of wide-eyed, open-book quality of someone much younger — he still struggles with how to talk about his own feelings, let alone in the painfully vulnerable terms Reed needed.

“I think Wade found it cathartic,” Safechuck said of Reed’s interview process. “I did not. It was not healing for me.”

Safechuck went into the interview thinking it would unfold in a standard question-and-answer format. Instead, when Safechuck would finish talking, Reed would often silently roll his fingers to get him to keep going. “And I’m like, Wait, where’s the next question?” Safechuck said. “I don’t talk a lot. I’m not used to that, so that was hard.”

If Robson found the act of the interviews themselves to be ultimately therapeutic, it’s been the experience of watching audiences react to the finished film that has been the most revelatory for Safechuck.

“Because I lived through the abuse, it seems normal,” he said. “So seeing other people react to it is like, ‘Oh, man. Yeah, that is — that is terrible. That is a horrible thing to do to somebody.’”

To keep the filmmaking process as simple as possible, Reed prefers to keep his crew to the absolute bare minimum. For Leaving Neverland, he set up the lights and operated the main camera himself, while his assistant producer Marguerite Gaudin operated the sound and secondary camera. And that was it.

“When you’re interviewing a guy for three days about child sexual abuse, you don’t want the room full of people shuffling their feet,” he said.

That was especially important when Reed began asking Safechuck and Robson about the explicit, physical details of their sexual experiences with Jackson, so the audience could get a complete picture of the extent of the abuse both men allege they endured. Describing the nature of the sexual acts they say Jackson engaged them in — sometimes multiple times a day — over many years was, understandably, the biggest challenge for them. It wasn’t just due to how nauseating it is to hear those details now, but also because Reed had tasked them with recounting the breadth of their experiences from the perspective of how they experienced it at the time. And at the time, as children, neither Safechuck nor Robson believed the sex was abuse; instead, they understood it as they say Jackson presented it to them: the way they expressed their love for each other.

“We’d spoken about those details a good amount in our separate therapy experiences,” said Robson. “But by the time it was time to talk about the details of the abuse, I had already surrendered to being really present in the story. Then it was like, Oh, shit. Here comes this part and now I have to try and do this in the same way.”

“By the time it was time to talk about the details of the abuse … it was like, Oh, shit. Here comes this part.”

Robson doesn’t think he fully succeeded.

“I had developed a bit of a survival mechanism of becoming disconnected and cold and almost clinical in the way I would describe the details of the abuse,” he said. “I think you still kind of see that a little bit in the way I ended up explaining it in the film. I don’t decide to do it, but it just happens.”

Safechuck also had to remind himself that Leaving Neverland was only ever going to be able to capture a snapshot of whatever understanding he currently had of his experiences with Jackson. He would tell himself, “This is where I’m at now. Don’t worry about sounding stupid. Just say how you feel and just accept that this is you now, and the truth of how you feel about it now will shine through.”

But even that sense of forward progress — of being in a moment on a longer journey — was challenged after Reed contacted Safechuck last year for a half-day of follow-up questions. By the second day of their initial interview, Safechuck felt like he’d finally gotten comfortable with the open-ended rhythm the filmmaker was looking for. So for the follow-up, Safechuck thought, “This is going to be easy-peasy.” He even mentioned to Reed that he’d found some of the jewelry he’d told Reed that Jackson had given him. “And [Dan’s] like, ‘Great, bring it.’”

When the cameras started rolling again, Reed had Safechuck pull out the jewelry and explain the story behind it. According to Safechuck, Jackson gave him most of the items as rewards for performing certain sex acts together. And then there was the ring Jackson gave him during what Safechuck characterized as a mock wedding ceremony he and Jackson had together in Jackson’s bedroom.

Safechuck had already mentioned the wedding offhand to Reed in their first interview, but talking about it again, in more detail, while actually holding the ring itself, hit Safechuck like a freight train. Safechuck’s voice began to tremble, his face went white, and his hands started shaking uncontrollably. It’s one of the most distressing moments in the entire film.

“My body just went ‘boom,’” Safechuck said. “I thought I was past it. But, obviously, I am not.”

From the start, Reed understood that he was going to have to speak with Safechuck’s and Robson’s mothers, in order to answer the question he knew everyone would have: “How the heck did your mom let you sleep with a grown man every night?”

Answering that question occupies much of the first half of Leaving Neverland, as Robson, Safechuck, and their families recount the overpowering shock of Jackson’s sudden, all-consuming attention, and how Jackson used his larger-than-life celebrity to methodically ingratiate himself into their lives.

“What is striking is how quickly the mothers trusted this man, and how quickly he became part of the families’ lives,” Reed said. “Michael was such an intense presence as a kind of star that we don’t see anymore. His charisma and the luminosity and the wealth of his world was very attractive and fascinating. Would be to anyone. One can’t blame these families for being particularly blinded by that.”

But that’s exactly what both men knew would happen to their mothers by participating in Reed’s film. They had mixed feelings about putting them up for that kind of punishing scrutiny, because they also still had mixed feelings about their mom’s role in their abuse.

“She was going to receive a certain amount of negative pushback and, you know, blame for what happened,” Robson said. “Because I felt that towards her, as well, you know?”

Safechuck ruled out asking his mother, Stephanie, directly to participate, because he knew she would say yes to anything he asked.

“She, at this point, would do anything for me,” he said. “So I tried to have it be as much of her decision as possible.”

So he invited his mom over to his house while Reed was there, and let the filmmaker make his case on his own.

“Dan has a way,” he said, laughing. “Once they built their own relationship, she was like, ‘OK, I get what he’s trying to do.’”

Robson’s mom, Joy, was trickier.

“My mother was really suspicious of Dan and this film,” Robson said. “There’s a certain amount of, uh, denial in her life. I didn’t know to what degree she had processed everything that really has happened to me, and had happened to our family. So I didn’t know to what degree she’d be able to speak in a clear way about it all. But then I also had to realize, ‘You know what? Wherever she’s at, that’s the truth.’”

After the #MeToo movement began to dominate the national conversation, Joy did agree to speak with Reed, and Robson’s intuition about his mother proved to be accurate. In the film, Joy says she doesn’t want to know the details of what her son says Jackson did with him because she’s afraid it will give her nightmares. At the film’s premiere at Sundance, however, Robson said in the post-screening Q&A that Reed had screened the documentary for his mother. So she does know all the details now?

“No,” Robson said. “She, uh, she had Dan skip over the parts about the abuse.”

He grimaced.

“That’s a little challenging for me,” he said. “It’s like, come on, mom, you’ve gotta face this whole thing.”

Robson’s disappointment likely stems from how much Leaving Neverland forced him to confront how Jackson profoundly — and perniciously — affected his relationship with his father, who killed himself in 2002.

“[I was] realizing all sorts of connections I had never made before, connections to the ways Michael drove wedges between me and my father.”

“[I was] realizing all sorts of connections I had never made before, connections to the ways Michael drove wedges between me and my father,” he said. “[I was] also having more sadness and more regret because I was so drawn into Michael’s…what seemed like light at the time — that it was because of Michael, I understand now, that I was pushing my father away. Then me being a father now and imagining that, and how much that would break my heart. And how powerless my father must have felt at times.”

At this point, Robson paused, and shifted slightly in his seat. In Leaving Neverland, it’s never entirely clear what Robson’s father made of the attention Jackson was lavishing on his son, especially after the family, then based in Australia, left the 7-year-old Robson to stay with Jackson alone at Neverland Ranch while everyone else traveled on a planned vacation to the Grand Canyon. Robson says in Leaving Neverland that he and Jackson had sex multiple times during that period, establishing a pattern with Jackson that would persist off and on in Robson’s life for seven years.

But in his interview with BuzzFeed News, Robson made clear that his father’s relationship to his abuse is even more complicated than it appears in the film.

“I’ve learned in the last few years that he was also sexually abused, as a kid,” he said. “I never knew that when he was alive.”

Robson shifted again. He brought up the family’s first trip to Jackson’s Neverland Ranch when he says the abuse began.

“I learned this within the last, you know, whatever, five or six years,” he said. “My mother told me that my father said to my mother when he got on the plane to go back to Australia, ‘Let’s not tell everyone that Wade was sleeping in the room with Michael. People wouldn’t understand.’”

Safechuck’s already wide eyes went wider. “What to make of that?” he said.

Robson shook his head. “I don’t know what to do with that.”

Once Reed concluded his interviews with Safechuck and Robson, he began a monthslong corroboration process to confirm as much as possible about his subjects’ allegations. Reed also interviewed the investigators and prosecutors behind the 1993 sexual abuse case that Jackson settled for a reported $20 million out of court, and the 2005 sexual abuse trial for which the pop star was acquitted on all charges, although they don’t appear in the film.

“We found nothing contradicted Wade or James’ story, and we found quite a lot that also corroborated it,” he said. “For instance, James says he was first abused in Paris on the Bad tour. He was 10. He doesn’t remember the date. He stayed in a hotel, so we found out which hotel it was, and when Jackson stayed there, and what the tour dates were. We didn’t come across anything that would undermine or challenge James’ account.”

Reed also pointed to his approach to Safechuck’s and Robson’s interviews — including pressing them on why they say now they lied to support and protect Jackson — as another way he could test their truthfulness.

“That chronological, careful, detailed telling of a story over several days — that gave me great confidence,” he said. “I didn’t see any of the signs that I have picked up on in the past when people were being disingenuous or trying to shape the story. I’ve done so many interviews, I find myself being able to form a mental picture of what people are talking about. And if there is any part of that missing, then I’ll go back and say, ‘But hang on, you said this, and then later on you described it as this.’ … I found James’ and Wade’s accounts to be really internally consistent. Their whole manner was very open.”

Reed’s steadfast and full-throated belief that Safechuck’s and Robson’s accounts are credible and corroborated, however, has not stopped lawyers for the Jackson estate, and members of Jackson’s family, from repeatedly attacking Safechuck and Wade as mendacious opportunists out for their own monetary gain.

“It’s always been about money,” Taj Jackson, Michael’s nephew, said in an interview with CBS This Morning on Feb. 27. “I hate to say it. When it’s my uncle, it’s almost like they see a blank check.”

Robson’s and Safechuck’s lawsuits against Jackson’s estate and businesses are pending appeal after being dismissed on technical grounds unrelated to whether the claims of abuse are credible. But beyond whatever comes of the suits, the lasting impact Leaving Neverland could have on Michael Jackson’s legacy is difficult to measure — and the financial stakes for his estate and family could scarcely be higher. Billboard has estimated that Jackson’s music was streamed more than 1 billion times in 2017 alone; that Jackson’s recordings generate $20 million to $25 million a year worldwide; and that since his death in 2009, the estate has earned over $2 billion.

Perhaps that’s why, after sending a 10-page letter outlining a series of claims meant to discredit Safechuck’s and Robson’s credibility, the estate filed a $100 million lawsuit against HBO on the grounds that the documentary violates a nondisparagement clause in a 1992 contract between Jackson and the pay-cable network.

It’s also why two of the lawyers for Safechuck and Robson, as well as Reed and a publicist for the film, were present for their interview with BuzzFeed News. The only time the lawyers interrupted the interview was to note that the HBO letter was crafted by the estate’s attorneys and not the Jackson family, and to note that while Robson’s and Safechuck’s accounts are remarkably similar — establishing an alleged pattern of predatory behavior by Jackson — they aren’t completely the same. Reed, however, spoke up several times.

First, Reed explained why, even though he did ask Robson and Safechuck about their lawsuits, he didn’t use that portion of the interview in the film, and only devotes a few minutes to the suits in total.

“In order to put that aspect of the story in any kind of context, you have to explain what the court case is,” Reed said. “That’s a whole dimension that would’ve added a lot of time to the film.”

Then Reed jumped in to defend Robson and Safechuck against claims in the estate’s letter to HBO, which, among other things, cites examples of when the estate alleges the two men were untruthful in their litigation.

“It’s a nasty attempt, clutching at straws, to discredit something that they know is true.”

“Everything that’s in that 10-page letter just disintegrates under scrutiny,” Reed said. “There’s nothing that holds water in that.”

Robson and Safechuck also responded to some of the estate’s claims, mostly with confusion, such as that the men might have “aligned their stories” with their attorneys’ help when they met in 2014. “Both of our detailed claims were already written” before he and Safechuck met, Robson said.

The Jackson estate has also claimed that the mental breakdowns Robson had in 2011 and 2012 — which he says were caused by Jackson’s abuse, and led to him finally recognizing it as such — were actually the result of his family history of severe depression, specifically citing the suicide of Robson’s father, and the suicide of a paternal cousin in 2012.

Asked about this claim, Robson’s face hardened, and his lower lip began to shake with emotion.

“What the estate and the Jacksons are trying to do — with obviously no boundaries and no human limit in what they’ll do to protect the image [of] Michael Jackson, the cash cow — is maybe a slightly heightened example of what so many survivors go through,” Robson said. “In so many survivors’ cases, they’re not believed. They’re discredited, they’re shamed, by the perpetrator or people surrounding the perpetrator. And they’re revictimized over and over again. This is what the estate and the Jacksons are doing. They’re doing it to me, they’re doing it to James, but more importantly, they’re doing it to all survivors by these actions that they’re taking.”

He took a deep breath. “It’s a nasty attempt, clutching at straws, to discredit something that they know is true,” he said. “They’ve been hiding it and paying people off and shaming victims and terrifying victims of Michael’s for years. The thing is, I’m not going anywhere, James is not going anywhere. No matter what happens, I will never be silent again.”

Hours after the interview, Robson and Safechuck were seated before an audience filled with child sexual abuse survivors, and they were experiencing a much different reception. One man stood up, and, after first thanking Oprah for all her work for survivors, turned to Robson and Safechuck, and was suddenly overcome with emotion.

“Thank you,” he said. “God, from the bottom of my heart, thank you.”

Other high-profile survivors, like actor Anthony Edwards and retired pro football player Al Chesley, discussed their experiences, and Oprah hammered again and again at how predatory pedophiles ingratiate themselves into families to make themselves seem innocuous and indispensable.

At one point, Oprah asked Robson and Safechuck about their expectations for doing the documentary, and they repeated that they expected to be “mowed over,” as Robson put it.

“Other survivors — that was my audience,” Safechuck said. “Honestly, this moment, being with survivors, this is why you do the movie. This moment is why.”

Once the Oprah interview appeared to be over, and the audience had all stood up in a final round of applause, Robson took a half step to the front of the stage.

“I just wanted to say one thing to you guys,” he said quietly, his hands clasped together. “As so many of you know, being a survivor is so isolating — at least it is for a very long time. So to be in this space, with you guys, brothers and sisters in trauma and in triumph … I’m just so grateful.”

As the crowd applauded again, a few yelling out “We love you,” Robson turned back to Safechuck, and they wrapped their arms around each other. ●

Part 1 of Leaving Neverland premieres Sunday, March 3 at 8 p.m. ET on HBO, and Part 2 airs the next night, March 4, at the same time.