Fong’s Pizza is one of the weirdest places in Des Moines. When you walk in, the booths in the narrow room and the mural of a heron on the back wall may seem like you’ve just entered a traditional Chinese American restaurant.

But to the left, there’s a fully stocked midcentury tiki bar that serves craft beer on tap and cocktails in heavy plastic cups etched with cartoonish iconography.

Fong's — a popular restaurant that’s been featured on shows like Man v. Food and The Best Thing I Ever Ate — is a Frankenstein exercise in American fusion. The menu features Chinese cheese sticks (mozzarella cheese encased in an egg roll wrapper and served with marinara sauce) alongside crab rangoon pizza (the expected combination of cream cheese and artificial crab mixed with Asiago and mozzarella cheese, topped with a sweet chili sauce and crispy wontons). The pizza is made on a crust as thin and white as a saltine cracker.

The cultural tensions at work are illustrated in the origins of its name, chosen by a partner in the restaurant group that owns the place who also considers himself a movie buff. The “Fong” in Fong’s Pizza is an homage to Benson Fong, a Chinese American actor famous for his roles in Charlie Chan movies, a popular series of films from the mid–20th century. The films are widely considered controversial since the titular role of Charlie Chan was often played by an actor in yellowface.

Beneath all this, Fong's sits on a small piece of American history: the remodeled remains of King Ying Low, a vintage Chinese American restaurant that closed permanently in 2008 with little fanfare. At least a century old, King Ying Low was not only the oldest still-operating restaurant in Des Moines; it was one of the oldest still-operating Chinese American restaurants in the entire country. (Pekin Noodle Parlor in Butte, Montana, which opened in 1911, currently claims the title.)

Founded at a time when Chinese immigrants faced steep structural barriers in all aspects of life alongside pervasive racism, the history of King Ying Low is actually one history of Chinese Americans in the Midwest — and America. It’s a story of perseverance and survival in the face of contempt and persecution, but also a demonstration of how a small cultural minority embedded itself deep within the fabric of its community.

In a 1910 article, a reporter for the Register and Leader reported on the lack of New Year's celebration among the city’s 20 Chinese immigrants. Lee Din, the local founder of Chinese restaurant King Ying Low, was interviewed, lamenting the lack of festivities.

For Din and his fellow immigrants to Iowa, there was little to celebrate and more than enough reason for them to keep their heads down in their adopted city, which was less than welcoming.

Din had made his way to St. Paul and then Des Moines after initially immigrating from Guangzhou to San Francisco in 1880. When he opened the restaurant sometime between 1904 and 1907, Des Moines was still closer to its origins as a frontier town — a Manifest Destiny–era military settlement built upon the confluent banks of the Des Moines and Raccoon rivers — than to the insurance town filled with professionals, which the city would later become. Din and King Ying Low settled into the second floor of a building on Mulberry Street, above a saloon and below a medical school. It quickly became entrenched as one of the city’s few Chinese restaurants.

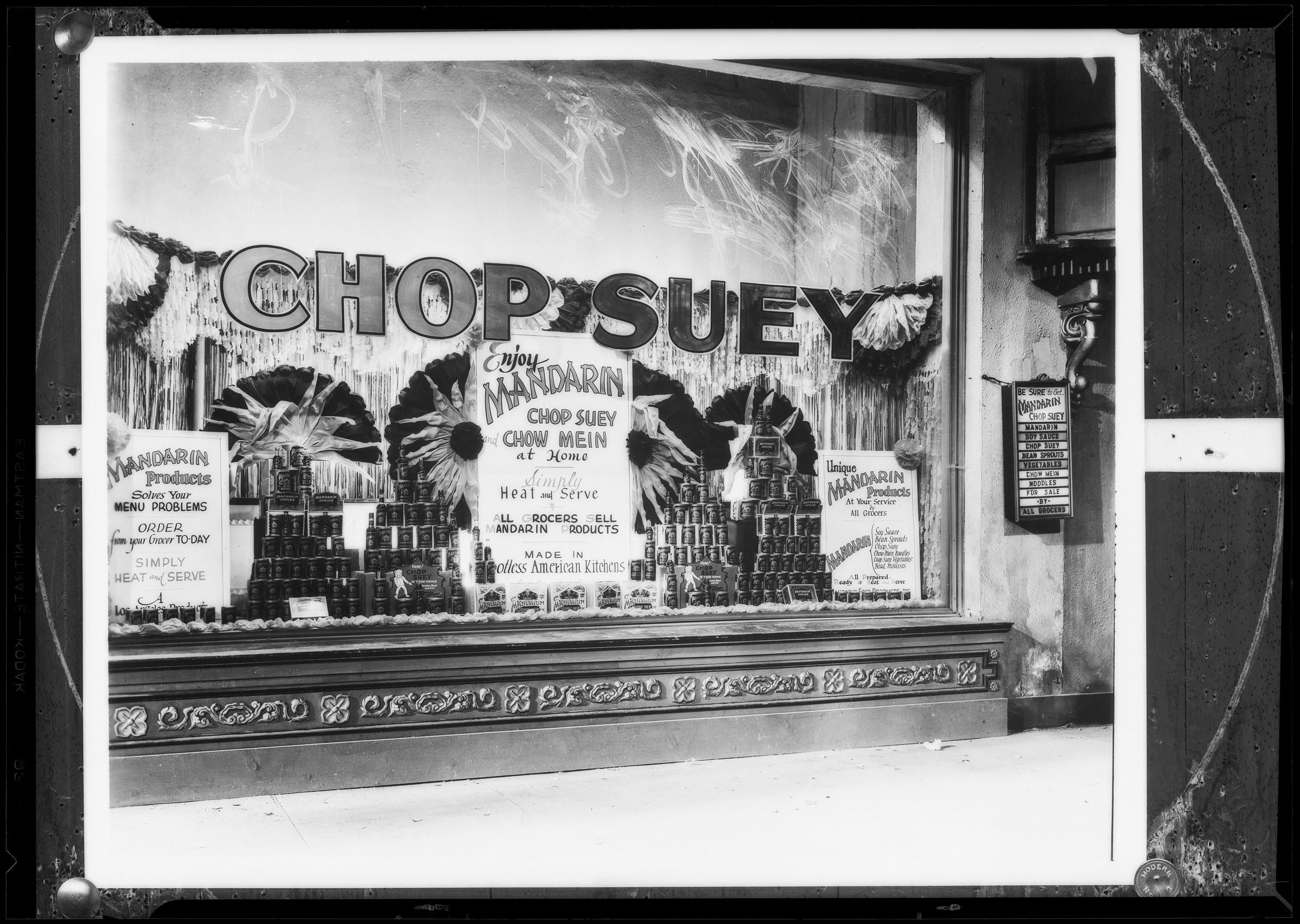

King Ying Low offered a limited menu in its early days and was largely organized around chop suey, a bland collection of meat, vegetables, and rice in a starchy sauce that has little in common with traditional Cantonese dishes but became immensely popular across America in the early 19th century, so ubiquitous that Chinese restaurants were mostly referred to as chop suey houses.

Mob violence and intense prejudice toward Chinese American communities plagued coastal cities in the years after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882. But the community in Des Moines, governed and policed by almost exclusively white settlers, presented its own problems to the success of his fledgling restaurant.

Immediately upon King Ying Low’s opening, the restaurant became an integral part of the heart of downtown Des Moines, then an area of never-closing saloons and pool halls that were home to the region’s most diverse, marginalized, and often criminalized populations. Almost as soon as he arrived, Din had to fight not just to ensure the survival of his own restaurant but for the survival of the small community of Chinese Americans who called Des Moines home.

The expansion of Chinese restaurants in America at the turn of the 19th century was an almost direct result of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Due to the restrictions imposed by the law and subsequently limited jobs available, these restaurants functioned as sustainable sources of income and ideal vehicles through which to sponsor the immigration of Chinese workers to America. King Ying Low was no different. Din was even arrested and fined in 1919 after he was accused of attempting to bribe an immigration officer by slipping a $100 bill in his pocket; the officer had found a problem with the papers of one of the restaurant’s employees.

Din's first appearance in the public record was in 1905, when he appeared in court on charges of keeping a “disorderly house” — essentially an accusation that he allowed prostitution at King Ying Low, after he was arrested with six women. Later, in 1911, he had to appeal a ruling by local law enforcement that barred women from visiting King Ying Low after a similar arrest by arguing that it was “no crime to feed women.”

The chop suey houses of downtown Des Moines, rather than the nearby saloons and dance halls, drew the particular ire of law enforcement throughout the first decade of King Ying Low’s existence. “The chop suey restaurant is the worst place left in Des Moines and it has to go,” proclaimed a Des Moines police chief in 1909 after a young woman from a well-to-do family was arrested in one.

The subsequent crackdown resulted in further raids and more arrests. Chinese American restaurant owners found themselves consistently brought up on charges of prostitution and indecency. A fellow downtown Chinese restaurateur named George Wee, who came to Des Moines in an attempt to expand Chicago’s chop suey tradition, was arrested and harangued by law enforcement so frequently that he was eventually forced to close his restaurant and was nearly deported. A pause in arrests in the spring of 1910 was so noticeable that it was remarked upon in the local paper. “The police must be pretty busy these days,” the comment reads. “They haven’t found time to raid the Chop Suey joint in over a week.”

The racist campaign to characterize chop suey restaurants as illicit and criminal didn’t go unanswered by Din. He donated large sums of money to local charities to address problems of poverty. When his son graduated from medical school back in Guangzhou, Din had his picture printed along with an announcement of his graduation in the paper for everyone in the community to see. When a union of Iowa laundry workers threatened a community of Chinese business owners in Des Moines in 1916, he stood against them as the community’s spokesperson.

As World War I erupted in Europe, Din became the vocal leader of a small minority of Chinese Americans in the Des Moines and weighed in on foreign policy. In multiple instances, he correctly predicted publicly that Japan’s power and empire expansion would continue to grow and entreated the United States to ally with China, something the country wouldn’t do until World War II. Though Din and his fellow Chinese American immigrants were not allowed citizenship and therefore could not be drafted, they all donated to the Red Cross.

As King Ying Low entered its second decade in Des Moines in 1924, Lee Din announced his intent to return to his native Guangzhou. His son was now a practicing doctor, and he hadn’t seen his wife in 20 years. By this time, his restaurant was already considered the “oldest chop suey house in Des Moines.”

In 1932, only a few years after taking over management of the restaurant, Charles Chong died of pneumonia, which he contracted while returning from San Francisco, where he was compelled to testify in the immigration trial of a former King Ying Low employee. His partner, Sun Leong, had barely taken sole ownership of the business when he too was subpoenaed to testify in yet another immigration trial in San Francisco.

His son, Louis Leong, stepped in to take full control of the restaurant. Like Din before him, Leong was called upon to represent his home country in his new community. As conflict with Japan began to seem more inevitable and the Second Sino-Japanese War loomed, the owner of King Ying Low, at 26, declared publicly that he would fight for China if he hadn’t immigrated to America.

During the lead-up to WWII and after the US entered the war, Leong led public charity drives to raise money for the Chinese relief. During and immediately after the war, the restaurant hosted several events held by the Iowa Socialist Party, including a speech on “America’s Role in Asia” by a writer who had also spoken out against Japanese internment during the war and dinner with a leading representative of Saskatchewan’s democratic socialist party.

By the end of the decade, King Ying Low had established itself on the ground floor of the Elliott Hotel, where it would remain until its closure. After an alliance with China during WWII finally prompted the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943 and King Ying Low had established its position as a pillar of Des Moines’ culinary scene under the steady hand of Leong, the restaurant settled into a long period of stability.

Despite the easing of immigration restrictions after WWII, Leong continued the King Ying Low tradition of using the restaurant to facilitate Chinese American immigration, this time within the context of the Cold War.

King Ying Low itself was a longtime staging ground for the progressive political movements that would make dramatic and lasting changes in Iowa during the ’60s and ’70s. Park Rinard — a liberal power broker who worked with painter Grant Wood before to orchestrate the campaigns, policy issues, and speeches that would successfully propel Democratic governors and members of Congress to victory — often used the restaurant as a base of operations for his wheeling and dealing in Des Moines.

The 1970s also brought an influx of restaurants to the Midwest. When Leong retired in 1975, his successors were a group of Chinese immigrant chefs. The chefs brought a new range of cuisine to the old chop suey house, led by Ludwig Young, a charismatic chef who chose the moniker for himself. (He claimed that Beethoven’s 5th Symphony was the first piece of Western music he’d ever heard, but he thought Bach was better.) A profile of King Ying Low’s new guard called the restaurant’s revamped cuisine “short on American chop suey and long on the sophisticated Mandarin school of Chinese cookery, with Szechuan specialties also, as well as the more familiar Cantonese.”

In stark relief to its early history, King Ying Low found itself being written about and judged on the authenticity of its Chinese food, decor, and service, as opposed to its ability to assimilate and survive in a community largely opposed to its existence.

Two reviews in the late ’70s highlighted this change, both by the same food critic. The first slammed the authenticity of King Ying Low and blamed the bad dining experience on the “occidental” waitress and the poor service she provided. A revision that came just a few years later remarked upon the “authentic” quality of the food and that many Asian Americans seemed to be eating at the restaurant.

In 1980, as the ownership of King Ying Low settled in and only 60 years after a reporter remarked upon the absence of Chinese New Year celebrations in Des Moines, the Register profiled Young and his family in honor of the same holiday, an article in which Young discussed Chinese cultural traditions and his own opinions on his home country.

Young and his family ran the restaurant, and they planned another (closer to the suburbs where many families continued to migrate). He began to choose textbooks and help develop a curriculum for the first Chinese-language classes offered in Des Moines Public Schools that, with a special permit, he planned to teach as well.

All these plans were cut abruptly short when Young died of cancer in 1987. The following year, Young’s predecessor, Louis Leong, also died of cancer at 77.

After decades as a Des Moines institution, King Ying Low entered the ’90s in crisis, especially as the city’s downtown completed its long transformation into a neighborhood where people worked but did not live. King Ying Low coasted through several decades of atrophy and cultural neglect that perfectly mirrored the status of its longtime neighborhood. (A final review in the Des Moines Register in 2005 rated the food as average, the atmosphere shabby, and the history not worth the hype.)

And so, in 2008, after a century of the restaurant's existence, generations of Chinese American immigrants, and decades spent as a cornerstone of Chinese American culture in the city where its pioneering founder had made his home, the final owner, Tony Wong, quietly announced King Ying Low’s permanent closure as the result of particularly damaging kitchen fire.

It's a complicated time for the traditional Chinese American restaurant. Retiring older owners have given way to restaurant closures. A younger generation of owners has brought more regionalized Chinese cuisines to the US, where a more diverse and globalized palette has made for a receptive audience. This, in turn, has sparked fraught debates about what authentic food really is: Generations of Chinese American restaurateurs have defended their approach to food as an authentic American style.

Placing Fong’s Pizza in that wider landscape is a difficult task. Within a year of King Ying Low’s closure, Full Court Press — one of two restaurant groups that own the majority of restaurants in downtown Des Moines, an area known for its kitschy, popular bars — bought the space. Originally, the plan was for a traditional late-night pizza joint. But the concept for the restaurant changed when the new owners surveyed the ruins.

“Seeing the pieces from this restaurant and, honestly, the history of it all, what a sad thing to have laid that to bed. We were inspired by them,” Gwen Page, co-owner and manager of Fong’s Pizza for the past decade, told BuzzFeed News.

The original concept for a tiki bar that served pizza expanded to accommodate the influence of this history, and Fong’s was born. Other than peeling away layers of wallpaper and adding a bar, the former King Ying Low’s layout remained mostly unchanged, with parts of the old decor directly incorporated into the new restaurant. A framed King Ying Low menu sits above the sticker-covered bar, anonymous among the multitude of bric-a-brac.

Without the purchase, the restaurant might have been completely gutted and changed into something completely different, the decor and history lost. In the wake of the catastrophic fire that destroyed 85,000 pieces at the Museum of Chinese in America in New York’s Chinatown, the preservation of this history feels especially urgent.

The concept of Chinese American pizza, simultaneously radical and broadly appealing to the takeout preferences forged through decades of culinary evolution and tradition in the 20th century, has also been met with its fair share of skepticism. Early customers walked out after discovering there was no traditional Chinese American food being served. An early review in the Register dismissed the restaurant as “King Ying Kitsch.” (Since then, the restaurant has been featured on the Travel Channel series Man v. Food. It recently made a personal fan out of Alton Brown, which resulted in a feature on his Food Network show and personal praise on Twitter. It has also expanded, with three other locations in the state, the most of any Full Court Press brand.)

Page, a blonde mother of two who plays in a jam band in her spare time, said addressing concerns about cultural appropriation is just part of the modern restaurant world. But, she said, it's a complaint they seldom hear.

"Every once in a while, we'll get a comment that somebody is offended,” she said. “I think that goes with a lot of things. You have to be pretty sensitive anymore these days, which I am. That's something I'm very careful about. I think, early on, when we were still learning and growing, there may have been more opportunity to do that. We've evolved and streamlined, and the best way to be successful in business is to interact with your guests and get that feedback — and if you do hear a sort of comment that someone is caught off-guard or just not feeling that, I honor that and I take that very seriously. But I haven't really. The biggest complaints we get here are about waiting.”

For those looking to experience Des Moines’ Chinese American culinary history in its original form, direct descendants of the King Ying Low tradition can still be found in the city, just in a different neighborhood.

When Louis Leong retired and sold his restaurant in 1975, his son, Frank Lee, took up ownership of the restaurant Rice Bowl in Beaverdale, a tranquil, family-oriented neighborhood in the northwestern reaches of the city. The traditional Chinese American restaurant opened in 1966, and Lee brought his family recipes from King Ying Low when he took the helm.

Rice Bowl still stands today, just as it has for decades, now run by Kenny Lee, the grandson of Louis Leong. (The Lee family declined an interview.) Despite a national trend that sees the younger generation leaving multigenerational Chinese American restaurants for other careers, Rice Bowl remains a family affair with the 65-year-old Lee at the helm and his daughter, Jenna, assisting him. ●

Aaron Calvin is a writer living in Iowa.