For a brief moment last Tuesday after the Democratic presidential debate, past the hallways that snaked from the spin room to the exit near the back of the Gaillard Center in South Carolina, two of the candidates ended up stuck together in a small room, unable to leave.

There was a problem with the door — security needed to unlock it — and so they stood together waiting. Had chance put them there with anybody else, it might’ve been a moment of awkward silence. Amy Klobuchar and Bernie Sanders dislike plenty of people, but not each other.

The fact of their friendship, based on a little-discussed, yearslong mutual respect, is all at once entirely unexpected and intuitively obvious. As candidates, they shared a stubborn force of will and a fierce distaste for their enemies — both of them salty, but in vastly different ways. As senators, they work together all the time, but in matters of ideology and political sensibility, they agree on very little. He, for example, will hate this article — see: "political gossip," personality-driven media, etc. She already loves it.

“Hey, Bernie,” she told him in Charleston last Tuesday, flashing a little smile as they waited to leave the Gaillard Center, their respective SUVs idling outside in the dark. “BuzzFeed is writing a story about us.”

Klobuchar’s decision to drop out on the eve of Super Tuesday was a move aimed squarely at stopping Sanders’s rise — consolidating the moderate wing of the Democratic party. Sanders, meanwhile, spent Monday night in Klobuchar’s state, holding a rally with thousands in St. Paul. Klobuchar’s endorsement of Joe Biden on Monday, Sanders’ campaign suggested hours before his Minnesota event, changes nothing about their strategy.

But he is losing something rarer in this year’s presidential field: a friend.

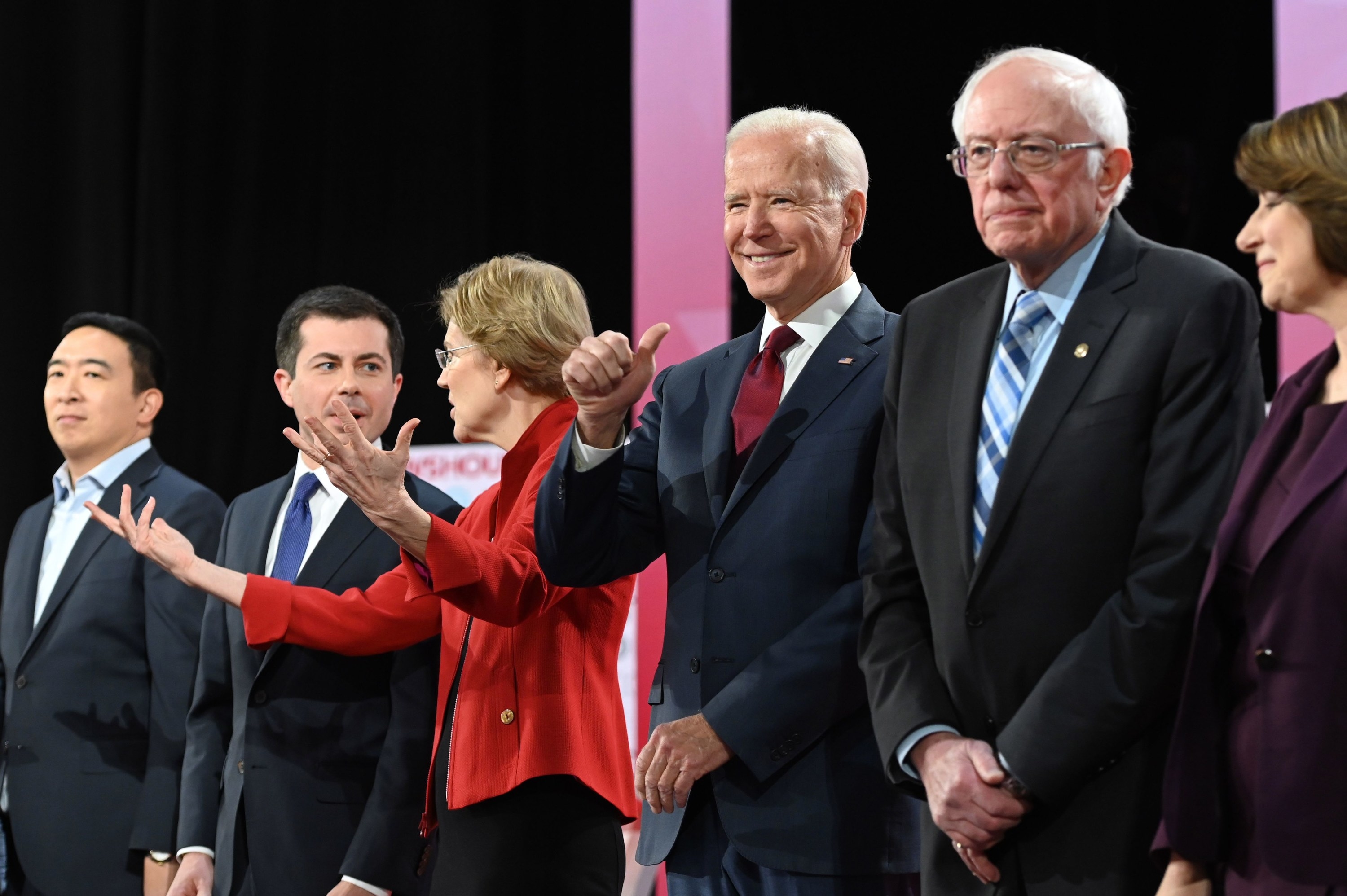

The Democratic primary drew a cumulative 28 candidates who, isolated from everyone but one another, forged unique relationships under the pressure of a unique experience. Amid the bizarre mix of personalities and political biographies on the presidential stage this year, Sanders and Klobuchar had this year’s most unlikely repartee — a puzzle of compatibility that even their own staffers can’t totally decode but cast as illuminating on both sides.

“She’s always willing to reach out to anyone,” a senior Klobuchar adviser said of the Minnesota senator’s efforts to pursue common ground across partisan lines, a fact of which they are quite proud. “But there’s a little personality match there that oddly works.”

“He likes people who are real and so does she,” a senior Sanders adviser said of the Vermont senator’s radar for political phoniness, a fact of which they are also quite proud. “Neither give a shit about putting on pretense.”

"I like Amy."

On Monday night in St. Paul, hours after she left the race, Sanders spoke about his fondness for Klobuchar. “We came into the Senate together in 2006, and she is one of the hardest workers that I know. I like Amy.”

The personality match, aides to both senators said in recent interviews, is undergirded in mutual respect in spite of their sizable disagreements. Sanders frequently talks about Klobuchar’s work ethic. (“She is always working,” he’ll say.) The moderate and progressive have partnered on multiple bills in the Senate, including one recent effort to import cheaper prescription drugs from Canada. (The amendment failed, with 13 Democrats also voting against it.)

In 2017, when CNN asked Sanders to participate in a televised debate on health care policy against Sen. Ted Cruz and another Republican, it was Sanders’s idea to invite Klobuchar to appear as his co-debater at the event. The two presented a tag team–like effect, mostly banding together over a topic that would sharply divide them in the Democratic primary a year later.

The personal relationship between Sanders and Klobuchar dates back more than a decade, when on a trip to Vermont, she and her husband, John Bessler, stopped to have dinner with Sanders and his wife, Jane, at a restaurant there.

More recently, in 2018, Sanders and Klobuchar ran into each other on a flight from Washington to Minneapolis. She was flying home. He was with three staffers, en route to campaign for candidates across the Midwest. When they got on the plane, Klobuchar moved to sit in the middle seat next to Sanders. When he had a problem with his ride to the hotel, she insisted on taking him herself. And when she walked him from the gate to baggage claim, introducing him to every Minnesotan she recognized along the way, she began by saying, “This is my friend Bernie.”

Outside, an aide was waiting in a sedan. There wasn’t enough room in the car, but without hesitation, Klobuchar put Sanders in the front seat and crammed into the backseat with his three staffers.

The two senators are both respected and influential among their Senate colleagues, but Klobuchar and Sanders also have a reputation for rubbing other Democrats the wrong way. Both can be tough on the people who work for them, though Klobuchar has been accused of harsher treatment, like throwing objects that strike staffers.

Former aides said Klobuchar could become obsessive about getting credit, particularly for bills that she sponsored, sometimes holding up other offices to ensure she got credit. In Senate tradition, the lead lawmaker on a bill has their name listed first; Klobuchar’s communications staffers are known for frequently emailing reporters who incorrectly list the order of names to correct the record, noting that their boss, not a different senator, is the lead on the bill.

In the New Hampshire debate that propelled Klobuchar to a surprising third-place finish in the state, Klobuchar was asked about Hillary Clinton’s biting assertion about Bernie in a January interview: “Nobody likes him. Nobody wants to work with him. He got nothing done.”

"I like Bernie just fine."

“I like Bernie just fine,” Klobuchar said onstage, referencing their work on the 2017 pharmaceutical amendment.

“We actually had a vote late at night one time, the Klobuchar–Sanders amendment to—”

Sanders interrupted, leaning over to look at Klobuchar at the podium next to him.

He broke into a grin.

“I thought it was Sanders–Klobuchar? No?” he said.

“Nope, nope, nope, it was not. It was not,” Klobuchar said.

The field of departed candidates now vastly outnumbers the five remaining trying to make it to the White House. But all of them learned for themselves that running for president is a strange and lonely business. People can watch up close — staffers and advisers, friends and partners, reporters and volunteers — but only those who have done it know the singular experience.

Months before he ended his campaign, after a day of long drives and small crowds across Iowa, Rep. Eric Swalwell returned to his hotel in Des Moines around midnight, ordered a plate of deviled eggs for dinner from the lobby bar, and talked with reporters about how much he missed his 6-month-old kid at home in California. Elizabeth Warren told NBC News the experience “can be thrilling but also very lonely.” And Andrew Yang, the entrepreneur who dropped out of the race last month, recalled the slog of early party dinners in Iowa and New Hampshire.

“Frankly it was a lot of the other second-tier candidates — and those events were kind of lonesome,” he said in an interview. “You show up and people are very polite, but a lot of them are just being courteous. Some of them don’t even know who you are. Then you go out there and you do your thing and you hope they like it. There’s a lot of putting yourself out there, so you naturally empathize with the other people who are putting themselves out there in that setting too.”

“There is a real bonding experience and kinship that comes with this process,” Yang said.

At party dinners, debates, and parades over the last 14 months, against the super-serious backdrop of a race to unseat Donald Trump, genuine relationships flourished between certain candidates with small gestures.

Yang remembered agreeing to switch time slots at a town hall–style event with Klobuchar. “From there I think Amy and I had a better connection,” he said.

Pete Buttigieg tried setting up a series of “get-to-know-you” calls with candidates he didn’t know well, such as Kamala Harris, according to three of his former staffers.

Tom Steyer, the California billionaire who dropped out of the race last weekend, made it a habit to methodically say “goodnight” to the candidates at the end of every debate, including once when he famously interrupted Sanders and Warren in the middle of a heated confrontation in Des Moines.

“The stakes are amazingly serious. It can’t be any more serious. So could we please have some joy as we go about life in the meantime and treat each other well?” Steyer said, laughing in an interview before he left the race.

“Are you kidding me? What a cast!” he said.

Klobuchar and Sanders, two of the most serious and stubborn candidates to run in the last year, didn’t exactly find “joy” in one another. But they did find common admiration for their work.

At the debate in New Hampshire, Klobuchar went on to talk about her own “receipts” — her bipartisan bills, her victories in Republican districts in Minnesota, and her large number of newspaper endorsements, another particular obsession of Klobuchar’s.

She listed all three of the New Hampshire papers that had endorsed her.

“I must confess, I don’t get too many newspapers’ editorial support,” Sanders said when she was finished. “Must confess that.”

“What do you mean — you got the Conway endorsement,” Klobuchar interrupted, turning to Sanders — a reference to the Conway Daily Sun, another local newspaper in New Hampshire.

“I did. We’re very proud of that.”

Klobuchar gestured to him, satisfied, and turned back to the audience. “There we go.”