More than 20 years ago, President Donald Trump’s nominee for the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh, wrote a memo that included an argument that the president likely would have to testify before a grand jury if subpoenaed to do so.

“Why should the President be different from anyone else for purposes of responding to a grand jury subpoena ad testificandum?” Kavanaugh wrote, using the formal legal term for the subpoena calling a person to testify.

The paragraph was part of a Jan. 25, 1995, memo to independent counsel Ken Starr and others about whether sworn statements made by then-president Bill Clinton and then-first lady Hillary Clinton were protected from disclosure under grand jury secrecy rules.

Kavanaugh, currently a federal appeals court judge, wrote then that he was providing “a brief written outline of the issue, as well as my views on it,” in advance of a scheduled meeting.

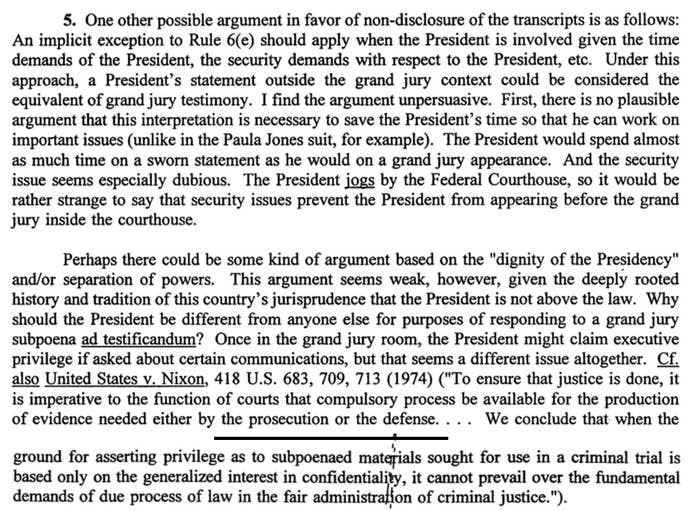

In concluding that the rule on grand jury secrecy wouldn’t apply to the statements, which were not made to the grand jury or compelled by a subpoena, Kavanaugh also considered whether there might be some “implicit exception ... when the President is involved,” due to time and security demands on the president being such that statements made outside of the grand jury should be treated as if they were before the grand jury. “I find the argument unpersuasive,” Kavanaugh wrote, detailing his reasons for discounting both rationales.

Then, he looked more broadly, writing, “Perhaps there could be some kind of argument based on the ‘dignity of the Presidency’ and/or separation of powers.”

Not so, he answered: “This argument seems weak, however, given the deeply rooted history and tradition of this country’s jurisprudence that the President is not above the law.” Kavanaugh then went on to pose that rhetorical question: “Why should the President be different from anyone else for purposes of responding to a grand jury subpoena ad testificandum?”

If “anyone else” were to refuse a grand jury subpoena to testify, they could be found to be in contempt — as happened Friday with a witness called to testify before the grand jury being used in special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation.

That did not, however, mean that Kavanaugh thought there were no limits.

“Once in the grand jury room, the President might claim executive privilege if asked about certain communications, but that seems a different issue altogether,” Kavanaugh wrote.

The document was one of several — 4,714 pages — made public by the Senate Judiciary Committee and the National Archives on Friday. The Archives is reviewing documents related to Kavanaugh’s federal government jobs as part of his nomination to the Supreme Court.

Kavanaugh’s views on executive powers have been a topic of discussion in his meetings with senators over the summer, given his work for the independent counsel in the 1990s, two law review articles he wrote, and the current special counsel’s investigation.