Henderson Hill and Rob Smith are the odd couple shepherding a collaborative effort to end the death penalty in America at the most significant moment for that movement in decades.

As talk of mass incarceration, racial disparities, and criminal justice legislation has permeated the public debate on both sides of the political spectrum, another effort has taken shape under the radar: the laying of the groundwork for a Supreme Court ruling that the death penalty is unconstitutional, a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishments.

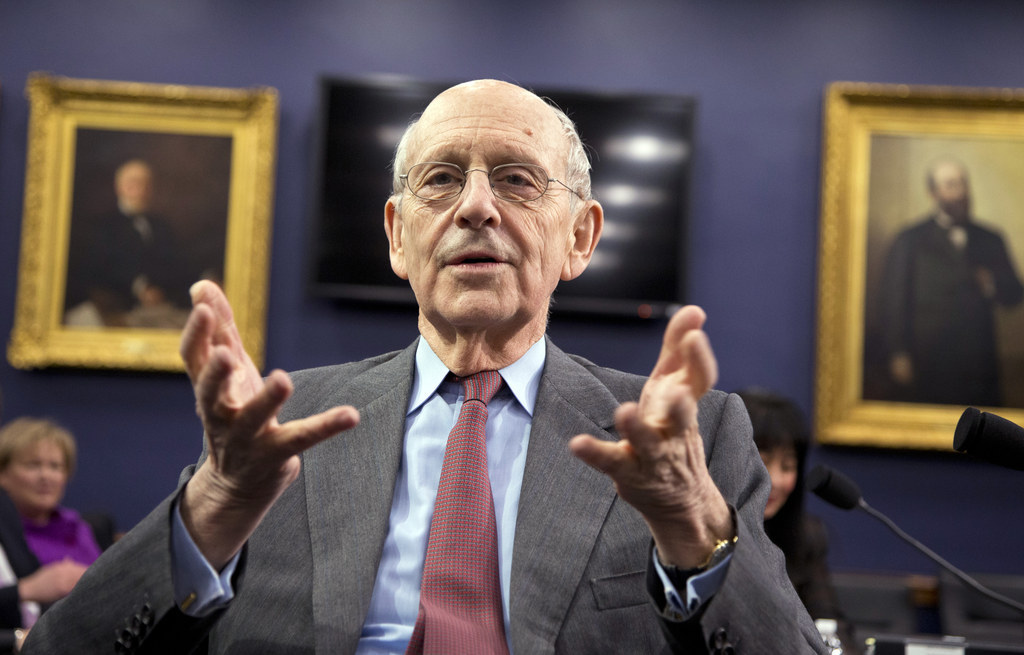

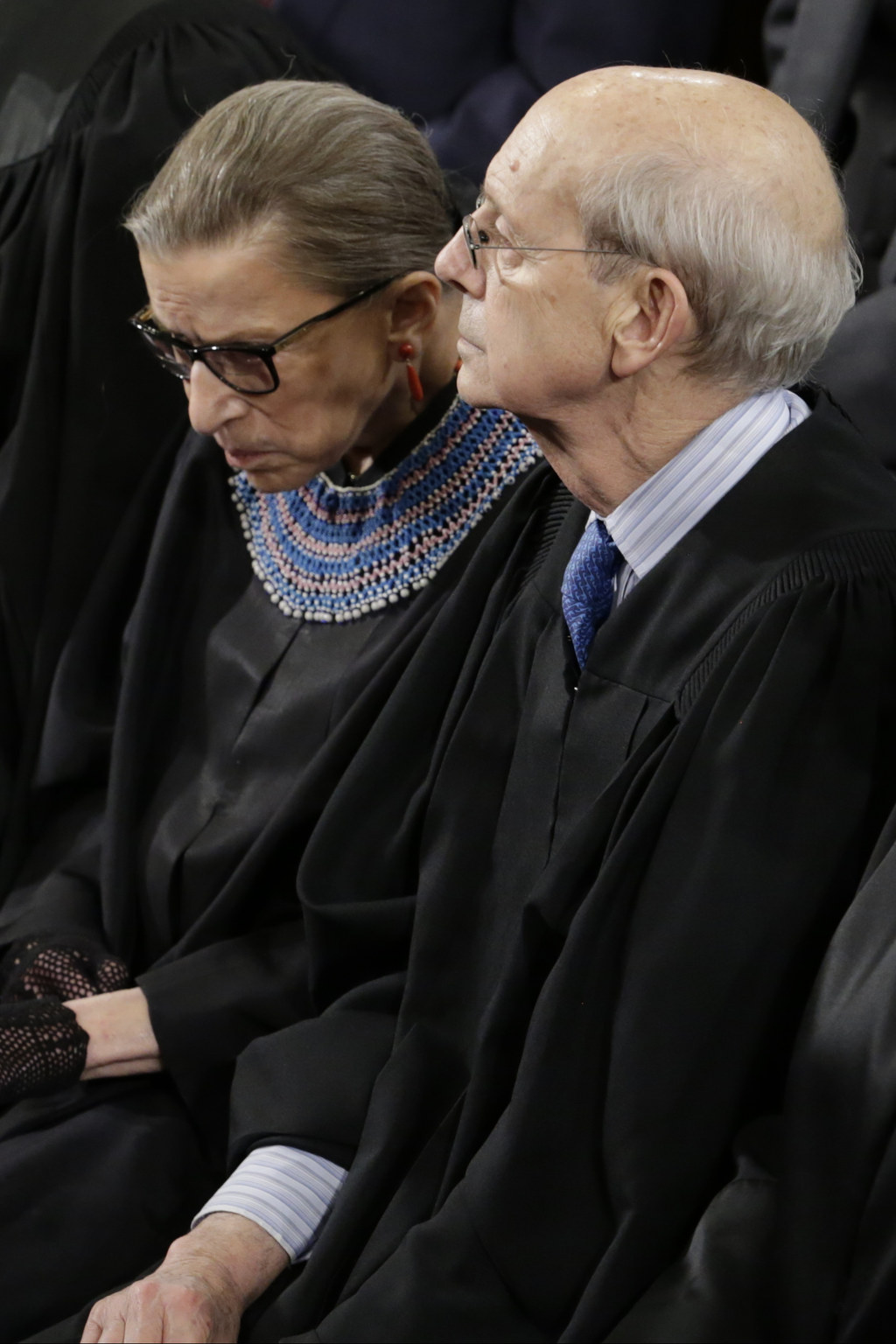

When Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, along with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, raised the prospect this June of the Supreme Court revisiting the constitutionality of the death penalty — using a key part of Smith’s work as evidence — the ground shifted overnight, and discussions went from hypothetical to hyperdrive.

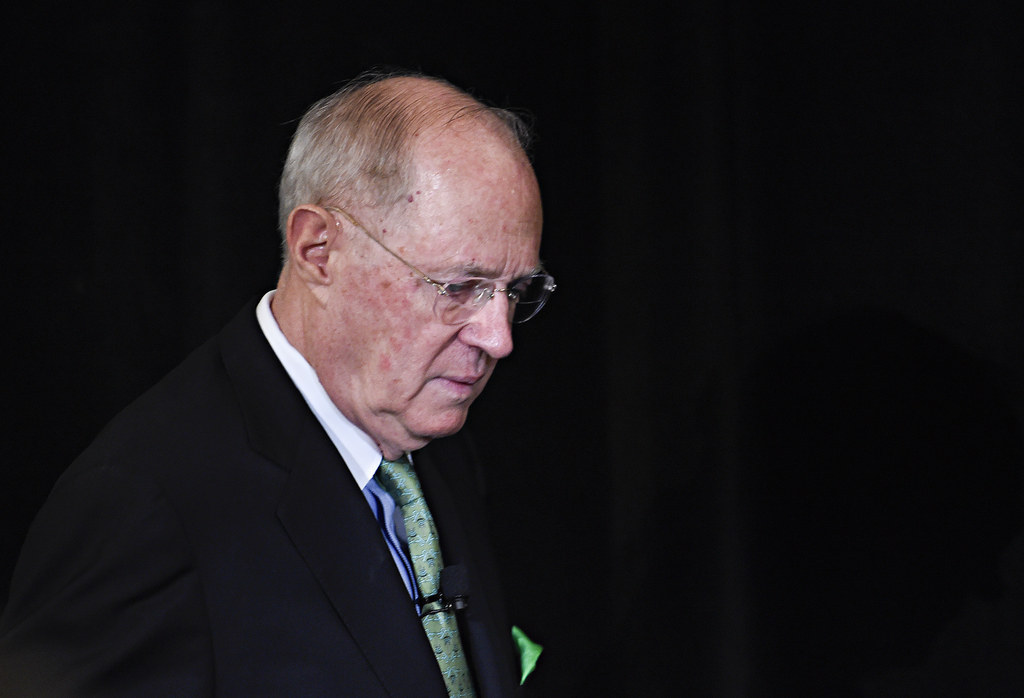

In the wake of that change, two of the death penalty’s most strident abolitionists sat down with BuzzFeed News to make their case not only for ending the death penalty in the United States — but for doing so in the next few years. The effort, as with so many focused on the Supreme Court, ultimately comes down to Justice Anthony Kennedy.

The 8th Amendment Project, which Hill and Smith run, is a centralized effort to advance death penalty abolition research, raise issues of legal system accountability, and help capital defense efforts — all with the Supreme Court in mind. It has a $1 million budget and six full-time staff members this year. It is part of a national effort backed by the Themis Fund, a donor collaborative dedicated to ending the death penalty in America, the fund’s director told BuzzFeed News. The Themis Fund was launched as an initiative of the progressive Proteus Fund in 2007, when a broad array of opponents of capital punishment — from litigators to funders — came together to figure out a way to end capital punishment in the country.

As death sentences and executions slowed down across the country — and some states got rid of it altogether — the Themis Fund donors decided to ramp up their efforts. In 2014, Hill, a 59-year-old black lawyer who began his career decades ago as a public defender, was made the head of the project, giving it its current name. He has since brought on Smith, a 34-year-old white law professor who graduated from law school in 2007, to serve as the project’s litigation director.

Hill first started defending prisoners on death row back in the 1990s. Smith left his job as a tenure-track professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill School of Law to join the project.

The first goal of the 8th Amendment Project is to solidify the foundation for a Supreme Court challenge to the constitutionality of the death penalty. It will do so, Hill explained, by focusing on providing evidence relating to three main areas: The death penalty is being imposed and implemented less and less often; the few counties that do so highlight fundamental problems with system itself; and the people who end up on death row are not “the worst of the worst” but are, instead, “the weakest of the weak.”

The 8th Amendment Project’s “ultimate mission,” though, is to support lawyers who actually bring cases to the Supreme Court that are aimed at ending the death penalty. This second goal, moreover, is already underway. The project is providing support in potential cases out of Louisiana and Texas, BuzzFeed News has learned.

"The criminal court system happens in the dark, and most people are just not aware of it."

As Hill put it, “That's who we are: We illuminate what the death penalty looks like when you look at the system up close, and we provide support to our partners and friends who seek to end the death penalty through a victory at the Supreme Court.”

Hill and Smith come at the issue from different worlds — and with subtly different aims — but their visions come together at the singular goal of getting a Supreme Court decision, within the next few years, that ends the death penalty.

“I think there’s a lot of optimism and confidence that the court’s close to declaring the death penalty unconstitutional,” Hill said. “And, I think that excitement helps to generate support for a [project] to coordinate efforts and to support efforts that are strategic and might help things along.”

Hill doesn’t take credit for getting the movement where it is — or even for what is happening now.

“It’s a diverse community, of dozens and dozens of organizations, that have been around and in the fight for 30 years that the attention is appropriately focused on,” he said. “I’m not representing a single client — and that’s the first time I’ve been able to say that in 35 years,” adding that he credits today's focus on race and the criminal justice system to the lawyers on the ground, people working in state legislatures, and researchers who have been doing the work.

Talking at length, though, with Hill and Smith provides a good picture of an aggressive arm of the abolition movement that sees the potential to end to the death penalty in America in the near future. After toiling for decades, this group believes, the effort is reaching its moment of truth.

As David Menschel, a prominent funder of and lawyer within the movement, said, “It’s time for the movement to be thinking about how it might bring a case to the Supreme Court — to hear what Breyer was saying.”

This is the story of how the death penalty abolition movement got here, and how — from Hill and Smith’s vantage point — they plan to win.

THE PAST: “I was 15, 16 years old, I was thrown to the ground spread-eagle by a cop in a criminal investigation. I’m in a suit and tie,” said Hill, in a light sweater and jacket, over dinner in September. “If it wasn’t for some white lady that came out and said, ‘This kid had nothing to do with anything,’ I’d have a mugshot.”

It was a series of decisions — before law school, after law school, all the way back to that day when he was a teenager, thrown on the ground — that transformed Hill into one of the leading advocates fighting against the death penalty.

He became a public defender in Washington, D.C., after graduating from Harvard Law School in 1981 — taking the path of defending clients who couldn't afford a lawyer because, as he said, he had seen the “the abuse of the criminal justice system, how it’s visited on folks of color.” But he didn’t take on the crusader role he’s since assumed. Hill was just another young lawyer working in D.C. “I was not one of those public defenders who went down South to take on a habeas while I was working on my caseload. That was not me. I wrote checks, small checks.”

About 10 years into his career, though, something changed. He had watched friends, like prominent NAACP Capital Litigation Project lawyer George Kendall, wage a battle against the death penalty. In 1976, the Supreme Court had restored capital punishment in the United States in Gregg v. Georgia, following legislative changes implemented after the court ruled in 1972 that the death penalty was unconstitutional.

“I thought I was as good a trial lawyer as there was — and if it was a shortage of qualified trial lawyers that were adding to our death row, that was something I was in a position to do,” Hill said. “And the need that I saw was the need that I’d been avoiding for 10 years.”

He moved to North Carolina in 1990 when he was named director of the North Carolina Resource Center, a project funded by the federal government to help improve the quality of representation for inmates on death row. In 1995, the center became its own nonprofit, the Center for Death Penalty Litigation. After working in the state for nearly a decade, two things changed. First, two of Hill’s clients were executed in 1999. “These were men that I’d worked with since I came to the state,” he said. “They had become friends of mine.”

Second, in 1999, death penalty policy conferences were organized, in part, to get Illinois Gov. George Ryan to place a moratorium on more executions. The effort, ultimately successful, came in the wake of the exonerations of prisoners in the state who had been on death row and evidence of wrongdoing by government officials. “[L]ooking at a justice system that was just corrupt in its use of investigative procedures, its use of police procedures, I think it had an impact of shocking the conscience and taking away the confidence,” Hill said.

It was then that Hill decided to change his focus. “This is a bizarre system. Litigation isn’t and wasn’t going to answer all of these questions,” he said. “There was a political fight that had to be engaged.”

Hill’s colleague at the 8th Amendment Project also went to Harvard Law School — but chose the path of a professor, not a trial lawyer. Smith, who admits he cares about the questions involved in an “almost naive” way at points, has a more philosophical approach.

“The government is supposed to be restrained,” he said. “If punishing serves some purpose … then we need to do that, but I think the government has this obligation to everybody to do so with a minimum level of dignity.”

And that dignity, he believes, hasn’t been upheld in the current environment. Over the past two years, botched executions in 2014, increased scrutiny on the actions of prosecutors that people like Smith characterize as being out of control, ongoing questions about the role of race in jury selection, and the larger focus on the criminal justice system all come together to make this a key moment.

“People are starting to pay attention — courts and legislatures and executives and just everyday people — and saying, ‘What are we doing? It’s too harsh, it’s not serving a purpose, and it’s counterproductive?’” he said. “The people on the receiving end of that excessiveness don’t have a lot of options to go and fix those problems for themselves.”

Hill has been working to fix those problems for decades, and yet voices the sense of helplessness that he felt as a witness to the execution of David Junior Brown, who became known as Dawud Abdullah Muhammed, in 1999.

“The notion that I’m sitting with their families, and every last appeal has failed, and there’s nothing that you can do, and all you can do is sit in this chamber next to the people whose Brady violations and misconduct led to handcuffing the court’s opportunity to sort out facts of both guilt and the appropriateness of punishment,” he said, referring to claims that government officials withheld evidence that harmed his client’s case at trial and sentencing. “They’re sitting in the front row, and I’m sitting holding his daughter’s hand?”

THE DISSENT: Four hours away from North Carolina’s execution chamber, the nine justices of the U.S. Supreme Court hear last-minute requests to halt executions on a near-weekly basis. Earlier this year, though, the Supreme Court took up one of those cases, bringing the court’s deep dive on the issue out into the open — and creating an enormous opportunity for the 8th Amendment Project.

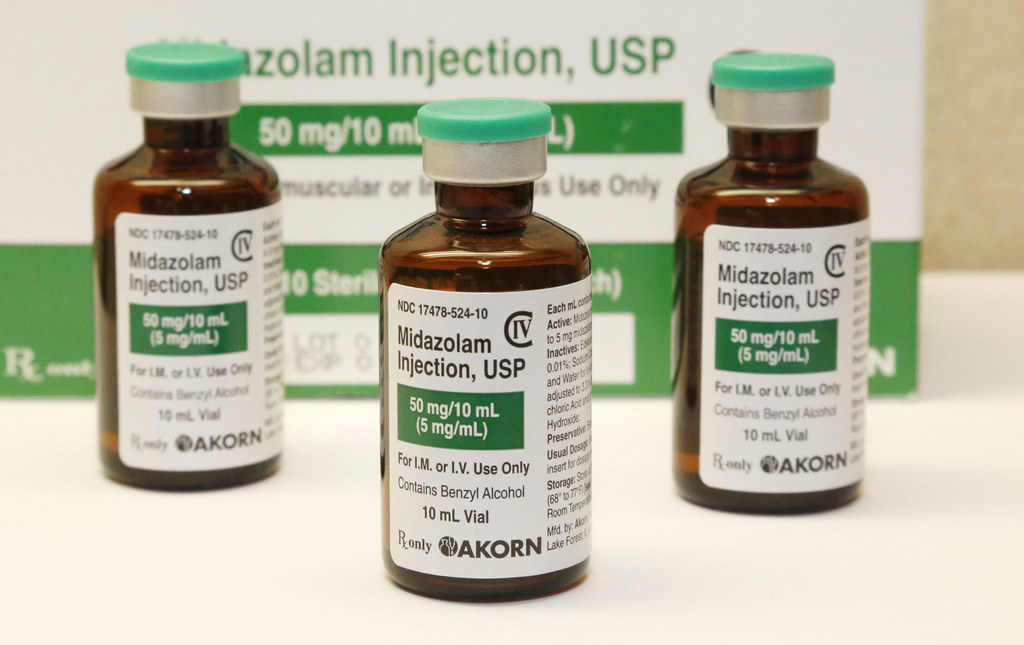

The court announced in January 2015 that it would be hearing a case brought by death row inmates in Oklahoma, challenging the state’s use of the sedative midazolam in its execution protocol. The drug had been used in the state’s botched execution of Clayton Lockett in early 2014, who sat up in the gurney and called out — after having been declared unconscious, leading the state’s director of corrections to call off the execution. Lockett died of a heart attack. Midazolam was used in two other problematic executions in 2014, one in Ohio and the other in Arizona.

The Supreme Court case turned on the specifics of the drug and whether its use created an “unacceptable risk of severe pain.” Additionally, in challenging the use of midazolam, there was an unresolved question about whether inmates needed to provide an alternative method of execution that was less likely to create such an unacceptable risk.

At the oral arguments in the case in April, and even more so when the Supreme Court’s decision came down in June, it was clear that the court is increasingly split on both the implementation of the death penalty in America and the broader question of the constitutionality of capital punishment.

During the arguments, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan aggressively questioned Oklahoma’s lawyer, but it was Justice Samuel Alito who made headlines by accusing death penalty opponents of waging a “guerrilla” war that left states unable to obtain previously used execution drugs and forced into trying new drugs like midazolam in executions.

Alito’s comments stirred up advocates like Hill, who said that while capital punishment opponents certainly are trying to figure out as many ways as possible of countering the death penalty, “[i]t just seemed way underneath the dignity of the court” to suggest that lawyers’ arguments “are not reflective of their clients’ needs or legitimate constitutional rights and are instead shills for some ‘guerrilla movement,’ some nefarious movement out there.”

Nonetheless, the Supreme Court upheld Oklahoma’s use of midazolam in June, making clear that, yes, inmates challenging a method of execution must provide an alternative means. The result in Glossip v. Gross was not a big surprise, but what was completely unexpected was the dissenting opinion written by Justice Stephen Breyer, an opinion joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“Rather than try to patch up the death penalty’s legal wounds one at a time, I would ask for full briefing on a more basic question: whether the death penalty violates the Constitution,” Breyer wrote.

“In 1976, the Court thought that the constitutional infirmities in the death penalty could be healed; the Court in effect delegated significant responsibility to the States to develop procedures that would protect against those constitutional problems,” he continued. “Almost 40 years of studies, surveys, and experience strongly indicate, however, that this effort has failed. Today’s administration of the death penalty involves three fundamental constitutional defects: (1) serious unreliability, (2) arbitrariness in application, and (3) unconscionably long delays that undermine the death penalty’s penological purpose. Perhaps as a result, (4) most places within the United States have abandoned its use.”

Breyer spent the next 39 pages laying out that case, concluding that “the death penalty, in and of itself, now likely constitutes a legally prohibited ‘cruel and unusual punishmen[t].’”

Advocates had not been expecting the move. Dale Baich, one of the federal public defenders who worked on the Glossip Supreme Court case, said that the dissent was surprising, in part, “because our approach to the case was to keep it very narrow. ‘This is just about midazolam.’” Yet, with Breyer’s dissent, that became the story — with even conservative Justice Antonin Scalia saying several times since June that he “wouldn’t be surprised” if the court ended up striking down capital punishment.

Death penalty opponents have seized the possibility of the moment. Capital punishment in the U.S. is “an increasingly well-documented disaster,” argues Cassandra Stubbs, the director of the American Civil Liberties Union Capital Punishment Project. And now, Breyer was on their side.

“That was about as comprehensive and deliberate a consideration of the problems that have plagued this punishment for 40 years since the reenactment,” Hill said.

Breyer’s dissent, Hill said, is nothing less than “a road map” for getting the court to end the death penalty. “It’s not like we’ve got to struggle and identify what would be sufficiently problematic to this court that it should lose confidence,” he said.

Those supporting the 8th Amendment Project say Breyer’s dissent also sent another key message, one about the possibility of getting Justice Kennedy’s vote in a challenge to the constitutionality of the death penalty itself. As a leading criminal defense lawyer, Ben Cohen with the Justice Center in Louisiana, put it: “Breyer wouldn’t have written that if he didn’t think there was a chance."

THE PROJECT: And so, taking Breyer’s lead, Hill and Smith are getting to work.

Menschel is a donor with the Vital Projects Fund — and lawyer who is prone to aggressive tweetstorms calling out politicians and journalists on criminal justice issues — who has supported the 8th Amendment Project’s work. He explained what he sees as the project’s two tracks.

One track, he said, is working on the issues that the court said it would need to address before it would find the death penalty unconstitutional — a track that he noted has been proceeding for a long time. For the 8th Amendment Project, this means providing additional evidence of those four issues detailed by Breyer: unreliability, arbitrariness, delays, and abandonment.

The second track, Menschel said, is preparing for the Supreme Court case itself. Quite simply, Menschel summarized, the 8th Amendment Project is “building a case — and also helping people improving the cases that they may be bringing.”

Hill and Smith were in New York City in September, meeting with funders over the next days seeking, as Hill put it, “the resources to conduct that kind of investigation and to bring that to life in such a way that it informs people.”

What does that actually look like, though?

Hill described their work as an effort to show that “the use of the death penalty is not an expression of the democratic process but actually can be traced either to idiosyncrasies of the elected DA or chief DA, the prosecutorial authority” within a specific county. In other counties, he continued, the evidence could show it’s part of “something broader … an oppressive justice system.”

In still other places, he said, it could show that the improper use of the death penalty “is not even just [a problem with] the justice system. It’s health care, it’s education, it’s employment, it’s every which way that the government interfaces with a certain part of the population. It’s oppressive, and the death penalty is just one of those elements.”

"That’s the power of Justice Breyer's dissent … to say, 'Tell us what this looks like here.' And we're going to tell him what it looks like."

Additionally, Smith said, the 8th Amendment Project also is looking — along with other groups like the ACLU — to see if “there states that are ready to repeal” the death penalty whether legislatively or, under state constitutions, through state courts.

Their work on the first track is focused on a tight timeline — over this next year — as Hill and Smith see the process moving quickly and likely leading to the big Supreme Court case being heard in the next two or three years.

Not everyone on their side agrees this is likely or possible or even advisable — at least not on the timeline Hill and Smith describe.

Stubbs, the ACLU lawyer, held back on giving a specific time frame, saying only that “the timeline is shortening until when we as a country will be moving away from the death penalty.” Kendall — the senior litigator involved in Supreme Court death cases for decades — is representative of an older group of litigators, skeptical of the Supreme Court’s actions on the death penalty. While writing in September that Breyer’s dissent “will command the most attention in the coming years,” his timeline put things off for quite a while — citing a nearly decade-long process within the court that led to the 1972 decision striking down states’ death penalty laws.

“It’s really scary when somebody a whole lot smarter than you says you’ve got no chance of getting Kennedy and so don’t try,” Cohen, the Louisiana defense lawyer, said of the skeptics’ voices. “One of the things I love about [Smith] is he’s just courageous. I’m going to represent my guys [in cases where I am the lawyer]. I do what I do in Louisiana. It’s sort of a no-brainer, what I do. But he’s got to step forward and say, ‘No, no, no, we are going to try.’”

Even outside of the 8th Amendment Project and lawyers they’re supporting, the fact is that last-minute requests come to the Supreme Court almost every week from people asking the justices to stop their executions — and any of the lawyers in those cases can raise this issue.

Stubbs acknowledged as much, saying, “I think what we know for sure is that Justice Breyer and Justice Ginsburg have real questions about the death penalty, that they have invited people to file those claims, so we can expect that people will file those claims."

THE COUNTIES: Until the court takes a case, though, the overwhelming focus of the 8th Amendment Project is on counties.

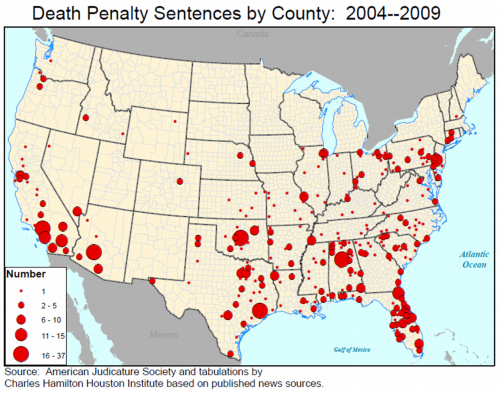

The strategy came about because Smith and others, including the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, concluded after significant research that many of the problems in the death penalty system were happening not throughout entire states — but within individual counties.

The research itself began when a lawyer in Louisiana found that death penalty sentences weren’t proportionally distributed through the state. Quite the opposite, in fact.

“There’s at least 38 parishes in Louisiana that have never returned a death sentence, and there’s some parishes that used to return lots of death sentences and don’t anymore — and it’s not for want of murders,” said Cohen, the defense lawyer in Louisiana. “There isn’t a state policy on the death penalty. These are the last bastions.”

After discovering that, Cohen wondered, “Is that a particular function of Louisiana?” Cohen had assumed that other states like Florida and Texas were producing death sentences regularly and proportionately, so he talked with Smith and others about the matter. Smith’s research, however, revealed that death sentences — in Louisiana, Texas, Florida, and everywhere still sentencing people to death — were now coming from just a few places.

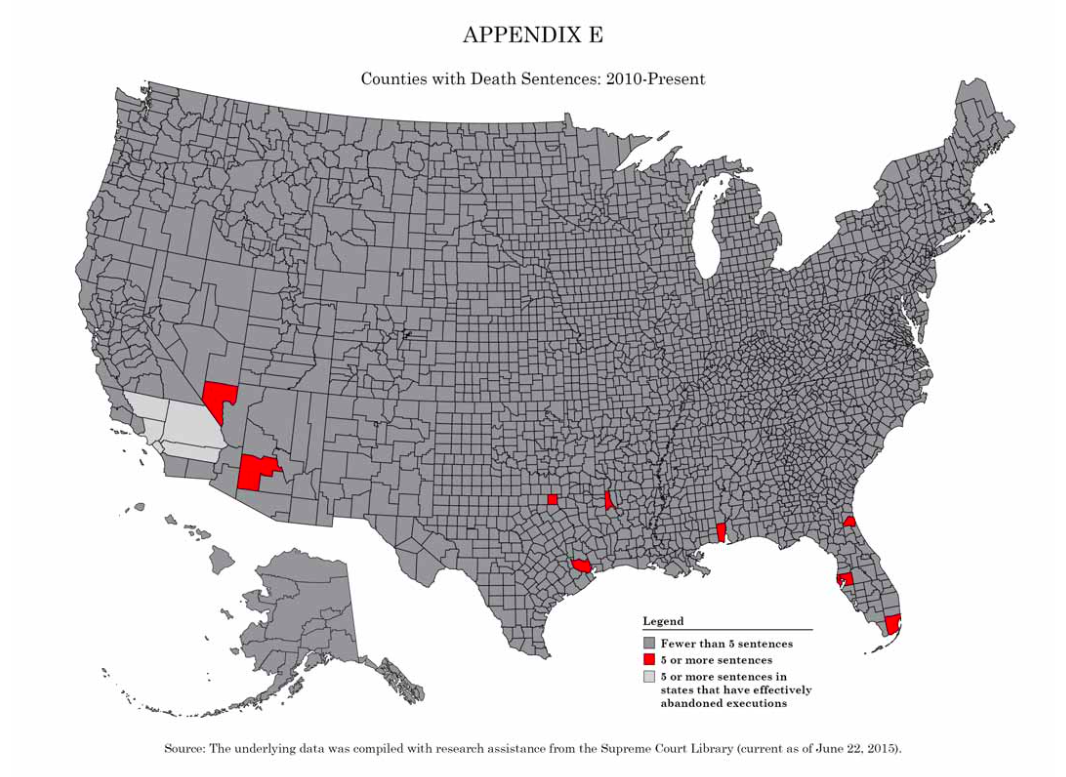

Smith published his findings in 2012 in the Boston University Law Review. He explained the importance of the findings for abolitionists, writing, “this clustering of death sentences around an isolated few counties provides the opportunity for targeted doctrinal, litigation, and advocacy strategies.” The paper included maps, showing the rarity of the death penalty when examined by county.

Cohen, who still works closely with Smith and now the 8th Amendment Project, said the research “changed the way we think about the death penalty.”

There are signs that’s not an understatement. “We work in the fields of the death penalty in Texas, and the county strategy is our life,” said Kathryn Kase, the executive director of Texas Defender Service, whose aim is not abolition but rather legal reform. Kase noted that while Texas has 254 counties, most of its death sentences come from a few, urban counties — a function, she said, of the way Texas funds its criminal justice system.

In June, Justice Breyer picked up the county data and ran with it in his dissenting opinion in Glossip. Throughout his dissent, he focused in on the county-by-county differences in death penalty, citing Smith’s study repeatedly and writing that “the imposition of the death penalty heavily depends on the county in which a defendant is tried.”

Breyer even expanded upon the maps created by Smith and his colleagues, creating new maps provided in the appendix to his dissent, including one showing that “between 2010 and 2015 (as of June 22), only 15 counties imposed five or more death sentences.”

Echoing concerns about prosecutors, defense counsel, judges, and more, Breyer wrote that “[t]he research strongly suggests that the death penalty is imposed arbitrarily.”

Now, for the 8th Amendment Project, the plan is to go through those counties — the red counties on Breyer’s charts — and figure out what’s actually leading to those death sentences. Primarily, the aim is to show how and why those counties are unusual. At the same time, Smith also hopes that by drawing attention to what’s happening in those counties, that could, itself, lead to changes within those counties.

The micro-attention on the counties, however, is never far removed from the primary goal of preparing to make this argument to the Supreme Court — a task made all the more difficult because the timing of that argument is unknown.

THE ARGUMENT: In the absence of a timeline, then, the 8th Amendment Project is working quickly, digging into the counties identified by Smith’s research and highlighted in Breyer’s dissent — places like Caddo Parish in Louisiana — to make the case against the death penalty.

In addition to sending the messages about arbitrariness and consensus to the courts — two of the four areas explored in Breyer’s dissent — Smith said this work also enables the project “to send that message back down to the local prosecutors.”

Caddo is the parish that’s made news because the current district attorney, Dale Cox, famously said earlier this year that the state should “kill more people.”

“We want to be able to show the Supreme Court how convincing this consensus is on the ground,” Smith said, “but we also want to be able to reflect back down and say, ‘You know, do you know how out of step you are with other prosecutors in your state and the country?’”

Cohen, who often represents clients sentenced to death in Caddo Parish, said that he’s reached the conclusion that the problems are inherent in the punishment itself.

“There’s something about seeking somebody else’s death that corrupts people … not financially, but corrupts their soul,” he said. “Prosecutors, to get up the courage and anger, it’s what makes [the death penalty] different. When you have death come in, it just becomes vicious. Part of that may be defense lawyers, scared for their client’s life, but part of that, I think, is prosecutors and judges getting up the anger that you need to kill somebody.”

Regardless of the reason for the actions taken by someone like Cox, Smith said, he hopes the attention he and others are placing on prosecutors leads to changes.

“Prosecutors are not used to people paying attention to what they’re doing,” Smith said. Their aim, he continued, is “to be able to say is, ‘This is Dale Cox, this is why he’s terrible, and this is what he’s done.’”

For his part, Hill connects the arguments raised about prosecutors to the earlier arguments from the late ’90s that helped lead him to his advocacy role.

“There seemed to be something about the death penalty itself that put these strange incentives, that put these bizarre political pressures on law enforcement and the district attorneys,” he said, “and these pressures impacted their fidelity to investigative process or to prosecutorial decisions.”

"Prosecutors, to get up the courage and anger, it's what makes [the death penalty] different. When you have death come in, it just becomes vicious."

Kase, with the Texas Defender Service, said concerns about innocence have changed the public perception about the death penalty in Texas.

“I think that what you’re seeing in Texas is this increasing realization that people are unsettled by the innocence cases. We had our 13th guy taken off death row this year, and the state dropped the charges against him” — a reference to Alfred Dewayne Brown, who was freed in June. “The case was reversed because the state coerced a grand jury witness into dropping her alibi for him and the state had failed to produce phone records showing that he was on a phone call with his girlfriend at the time he supposedly was killing this cop.”

Such concerns about innocence, Kase said, have led to a “huge drop in usage [of the death penalty], even in the urban counties” where the death penalty has been more prevalent in the state. The first death sentence in Texas this year wasn’t handed down until October.

Some of these problems, though, come about not because of overzealous prosecutors or police misconduct, Smith said, but because of “how terrible the representation systems are in a lot of those places that still use” the death penalty.

Smith said that, while the 8th Amendment Project and other efforts can’t flood the counties with “hundreds of millions of dollars to do that state’s job for them with their public defender systems,” they can try to stem the tide of death sentences.

“[I]f we put some effort … can we just keep the sentences low?” Smith said. “You want to be able to show that when you provide minimally adequate legal representation, that death sentences and executions stay low, and it furthers this consensus narrative.”

As with the benefit he sees in calling out prosecutors, Smith believes the same standard should go for defense attorneys, too. “If you’re not going to file any motions, and if you’re going to roll over on your clients,” he said, “people should know who it is that’s causing these major problems at these locations.”

Work over the past 15 years exposing and making the case about problems on all these fronts — from prosecutors and police to defense lawyers to innocence claims — has changed the criminal justice system, Hill asserts, in a way that has made their work at this moment possible.

Before all of this, he said, the criminal justice system had been operating behind the scenes — and he is passionate about the fact that he sees himself and the project as playing a role in changing that.

“The criminal court system happens in the dark, and most people are just not aware of it. To the extent we can sort of lift the cover off it in the 15 [counties with the] highest use of capital cases, we can begin to do that in the non-capital cases where these abuses really happen every single day,” he said. “Mass incarceration doesn’t start with federal court and these mandatory minimums. The federal court is the last stage of it.”

Summing their work up, Smith said, “So much of it has been so bad for so long, just nobody has been paying attention to it. That’s the power of Justice Breyer’s dissent … to say, ‘Tell us what this looks like here.’ And we’re going to tell him what it looks like.”

THE COURT: All of this leads eventually to that U.S. Supreme Court case challenging the constitutionality of the death penalty — a case that, almost certainly, would require the vote of Justice Anthony Kennedy in order to succeed.

While advocates disagree on the timeline for bringing a case to the Supreme Court — and the justices themselves have the ultimate say over whether they’ll take a case — it is clear that advocates see a key moment to be seized.

In some ways, the moment is already here. Lawyers out of several states already have raised the issue of the constitutionality of the death penalty to the justices in last-minute requests to halt upcoming executions — although the court has not yet taken up any of those requests.

In cases making their way to the court, the 8th Amendment Project has been providing support to lawyers behind potential cases out of Texas, with a legal team led by Neal Katyal of Hogan Lovells, and Louisiana, led by Cohen. Still other cases also are in the pipeline — including a case out of Pennsylvania, where a filing is expected at the Supreme Court by the federal defender's office this month.

In addition to lawyers bringing the claim in death penalty appeals, Menschel added, there also is the possibility that “the Supreme Court [could] grant cert in a death penalty case and add this question. It only takes four justices to do that.”

Much of the talk this summer was on the actions of the four justices who could do that: Breyer’s dissent; Ginsburg’s decision to join him; and the two other justices very skeptical of the punishment at oral arguments, Sotomayor and Kagan.

The real questions, however, have been aimed — as so many are — toward Kennedy.

Smith pointed to the fact that several key death penalty or related rulings in recent years have been decisions Kennedy wrote or joined.

He and others point, primarily, to Kennedy’s 2010 opinion for the court ending sentences of life without the possibility of parole for juveniles in non-murder cases. Kennedy earlier had written the majority decision ending the death penalty for juveniles, but, in the 2010 decision, Kennedy laid out a view that advocates find particularly helpful to their cause on how one shows a national consensus against a punishment.

Describing not only statutory bans on the punishment at issue, Kennedy also examined the use of the sentence in other states, finding that, in fact, only 12 jurisdictions actually sentenced juveniles to life without parole in non-murder cases. Kennedy wrote that such evidence shows that “[t]he sentencing practice now under consideration is exceedingly rare” and subsequently struck it down.

Smith and others also point to Kennedy’s decision for the court this past year striking down Florida’s statute setting a bright-line 70-IQ-point threshold, above which a person could not seek to be excluded from the death penalty because of intellectual disability. (Kennedy had joined the 2002 decision ending the death penalty for those with intellectual disabilities.)

In striking down the threshold provision, Kennedy wrote in part, “To enforce the Constitution’s protection of human dignity, this Court looks to the ‘evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.’” Again examining consensus of practice, in addition to law, Kennedy concluded there was “strong evidence of consensus that our society does not regard this strict cutoff as proper or humane.”

“It’s really scary when somebody a whole lot smarter than you says you’ve got no chance of getting [Justice] Kennedy and so don’t try.”

For Smith, this is the aim and the value of the 8th Amendment Project’s county work, as well as any statewide successes: “It’s a way of showing a consensus.”

He also sees these cases as providing insight, alongside Breyer’s dissent, that real change is afoot within the court. “[H]ere’s a court that has a jurisprudence that’s fluid, and they’re really starting to pay attention as it develops to the things that actually matter,” Smith said. “And it has five votes, including Justice Kennedy. You see it in a number of death penalty cases, and then you see it with juvenile life without parole, and you have Justice Kennedy talking about solitary confinement,” Smith said, referring to comments Kennedy has made over the course of this year about solitary confinement.

Baich said that, in light of those votes, he was watching Kennedy closely this April at the arguments over Glossip’s challenge to Oklahoma’s use of midazolam.

“I don’t know if you had a good view of Justice Kennedy during the argument in Glossip, but he looked to be very troubled. And, he asked really one question, and he was very gruff in the way that he asked it, but I saw him sort of sitting there with his hand holding his head up, and he just looked very troubled,” Baich said.

While he’s only speculating, Baich also said he had a reason for watching: “What we hear from his former clerks is that he takes death penalty cases very seriously, and that he’s troubled by them.”

This issue is, Smith said, a key role of the Supreme Court, and one where Kennedy’s vote — and philosophy — is key. “[T]he Eighth Amendment specifically tells them, uniquely, on excessive punishments, ‘Hey, there are going to be times where people’s retributive impulse is just too much, where they act too quick or they don’t have all the information,’” Smith said. “And the role of the courts is to be a restraining principle, and it really never has.”

Smith, Hill, and the 8th Amendment Project — along with other lawyers, advocates, and many others around the country — believe their work, and Kennedy’s views, could be leading to a change.

“Justice Kennedy and the court has to be thinking this is a chance to really make that promise from so long ago at the beginning of this country real in a sustained and permanent way,” Smith said, “I think [that] would just be an incredibly powerful thing to do. And given what they’re doing — not just the hope, but what they’ve been doing and saying — you have to imagine that it looks like we’re going in that direction.”