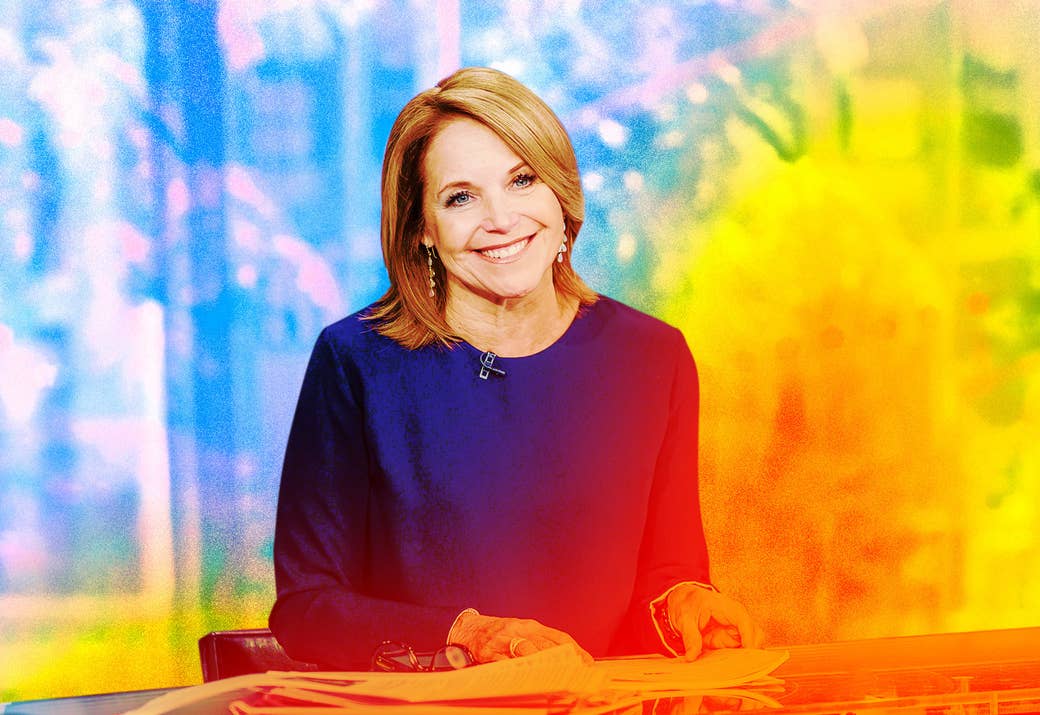

Morning shows have always been the crown jewels (and cash cows) of network television, bringing in massive advertising dollars with their high-low mix of sit-downs with world leaders and often wacky cooking segments. Even when the news business was less hospitable to women, the format helped launch the careers of broadcasters like Barbara Walters, Joan Lunden, and Jane Pauley. Arguably, though, no one became as successful and synonymous with the genre as the Today show’s Katie Couric.

As Couric puts it in her revealing new memoir, Going There, morning TV was the place where she could “comfortably converse with the Senate majority leader and the Teletubbies on the same morning.” Her willingness to share aspects of her personal life with viewers, from her two pregnancies progressing onscreen to allowing cameras into her colon after her husband’s death from cancer, helped her transcend simply being a news anchor: She became America’s morning show sweetheart in the ’90s. (And, later, a tabloid target.) But, in a surprising move at the time, she left morning television to slide into the CBS Evening News anchor chair in the aughts and later helmed her own daytime talk show, both less successful ventures she examines self-critically in her memoir.

The book has already made headlines for her candid writing about the media business; some outlets highlighted her thoughts about now-disgraced coanchor Matt Lauer and former colleague Deborah Norville, deeming the memoir vendetta-driven and misogynistic. But her memoir is actually an often-thoughtful look at the now-64-year-old Couric’s decadeslong career, tackling the ways she — and women of her generation — felt boxed in by gendered demands for relatability, even as she benefited from being able to meet that demand.

It was Couric’s relationship with her father — a journalist turned frustrated public relations man — who inspired her love of journalism. She admits that it was as much for him as for herself that she initially pursued her career, even though she eventually came to love the adrenaline of pursuing stories.

Her first job was in Miami local news, then a mecca for “if it bleeds it leads” crime stories, and then she transitioned to a reporter in the early days of CNN, where she struggled with the basics of teleprompters. She moved to Pentagon coverage at NBC after being warned not to become one of those “cute girls who does features.”

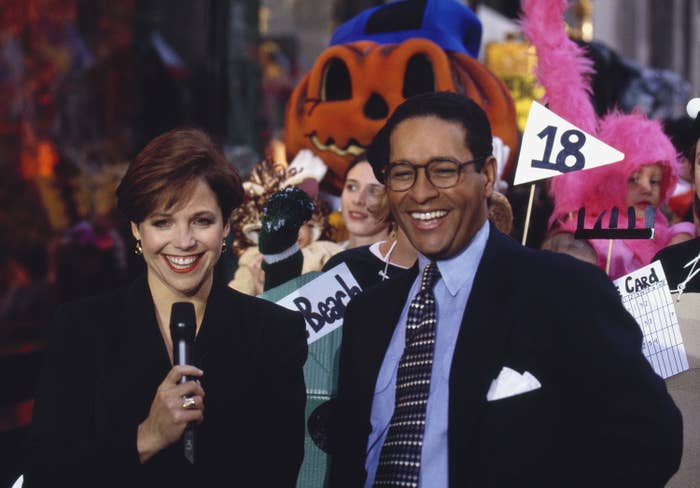

It was in the jump to Today in 1989 that Couric began to find her footing as a combination news anchor and hammy host. Taking over for Norville, Couric also started figuring out how to navigate being a public figure and the gendered media coverage that came with it. In her move, Couric had stepped into the ongoing controversy surrounding Norville’s replacement of Today coanchor Jane Pauley. Norville, with her glamorous blonde looks and former pageant-winning air, was seen as chief villain against spurned everywoman Pauley. And whether in response to the backlash against Norville or not, Couric cultivated a nonthreatening sensibility for her turn as anchor.

From her short hair (termed a “defiant mop” by columnists) to a wardrobe featuring accessible brands like Gap and Ann Taylor, Couric seemingly worked hard to make sure the audience identified with her. As she developed her relationship with “cock of the walk” cohost Bryant Gumbel, who respected her background covering the Pentagon, and later Matt Lauer, with whom she developed winning onscreen chemistry, she came off as one of the boys, joking with them on camera. But while she seems to be somewhat aware of why the corporate structure deemed her the “right” kind of woman, it’s still unclear how she really feels about those parameters.

Still, she writes with sensitivity — and a little PSA-ish earnestness — about the way her mother passed on her disordered eating onto her and about her experience with postpartum depression. Her sense for titillating detail, particularly about puffed-up masculine egos, never fails, from Les Moonves’ bad breath to Tom Cruise's too-tight black shirt and her encounters with men like Neil Simon and Larry King.

Couric also doesn’t shy away from discussing her personal life, including how her marriage to Jay Monahan devolved — before his death of colon cancer — as she became a household name and bigger star than her husband. She candidly details how fraught it was between the couple when he left corporate law to provide TV commentary for big true crime stories, seemingly moving into her turf.

Couric is also willing to grapple with the failures of ’90s media, giving us a peek into the morning TV melodrama sausage factory, including moments she thought went a little far. During an interview with a Black father and a white sibling of the 1999 Columbine shooting victims, producer Jeff Zucker asked for shots of their hands together in what she calls an unnecessarily exploitative moment. She expresses regret for the show’s framing of the 1992 LA riots; rather than contextualizing the anger of Black protesters, they focused on Reginald Denny, the white truck driver who was beaten up. She also apologizes for the cluelessly invasive questions she asked on Katie about Carmen Carrera's and Laverne Cox’s bodies.

Couric tracks how, as her professional trajectory soared, public opinion of her soured. By the early aughts, her salary was $65 million; she was battling for guest bookings with Diane Sawyer, losing relatability, and being dismissed in the tabloids and press as a “diva.”

She frames her time in the CBS Evening News anchor chair from 2006 to 2011 as a culture clash between her and the CBS “boys club,” saying that Les Moonves brought her in without properly introducing her to the power holders. But she doesn’t necessarily contextualize her own trajectory within the broader, changing news landscape — for instance, that evening news was in some ways losing ratings and relevance in the internet age. While she had ridden the wave of morning shows’ peak, she got to the party too late for evening news to matter (despite her big moment exposing Sarah Palin’s lack of expertise during the 2008 presidential election). And in the Daily Show era, her perspective wasn’t that specific or fresh beyond fiddling with the aesthetics of the old-school nightly news format, like standing up from behind the desk and addressing the viewers as “everyone.”

Her other misfire, the 2012 daytime talk show Katie, is a case study in how big budgets and market research pushed her from being, as she puts it, a journalist with a personality to a TV personality. “The music, the mood, my face, my voice are all so relentlessly chirpy — watching it now makes me cringe,” she writes of that era. And her efforts fell flat because, yet again, her timing was off: She was too early to catch the daytime talk show revival spearheaded by celebrity women like Drew Barrymore and Kelly Clarkson, who successfully leaned into their celebrity personas to attract viewers.

Couric seems to have struggled with an internalized distinction between “serious” news and human-interest fare, a gendered dichotomy that has since lessened its grip on the news landscape. She admits she was losing touch with popular culture by the time she segued into trying to help revive Yahoo News, and that coming from a local news background made her feel estranged from young colleagues who came up solely online. But now through her newsletter, Wake-Up Call, and the social media landscape, she says she gets to unite her strengths and interests and be herself again. “Sometimes I’m Katherine, sometimes I’m Katie,” she writes about the push and pull between her lighthearted and hard-news sides. “Now my work allows me to be both.” Her memoir successfully achieves this balance too.

Perhaps one of the most anticipated topics she addresses is her relationship with Lauer and how it devolved after his #MeToo downfall. Her retelling is a compelling anatomy of the way powerful men relate to women they consider peers while hiding a predatory side. She includes text messages to illustrate how their collegial work relationship quietly fell apart in the aftermath of the allegations against Lauer.

As she ponders why she never saw that side of him, she never quite hits on the fact that she became a powerful white woman at the network, and she didn’t see certain things precisely because of her positioning. And while she can now acknowledge the Today show’s white-centric melodramatic racial politics, Gumbel’s tawdry jokes about other women, and the gender politics of Norville’s sidelining, noting those things at the time and calling them out would have made her seem troublesome and affected her own career. The memoir could have been even stronger if it had explored the stakes around these issues even more.

Toward the end of Going There, Couric laments with self-awareness that it’s sad not to be the It girl anymore. But the insights in her memoir illustrate how the ways in which she saw the world — including the limitations — allowed her to hold that position for so many people for so long. ●