These are boom times for scandal recycling. From the skating world’s “bad girl” Tonya Harding to the “spoiled” parricidal Menendez brothers, it appears as if every infamous figure previously paraded across cable news and tabloids is being reconsidered and repackaged as higher-brow entertainment. Television auteur Ryan Murphy helped inaugurate this wave of prestige scandalmongering as one of the producers of 2016’s Emmy award–winning series The People v. O.J. Simpson. And since then, the visionary writer, director, and showrunner has set up a factory-like production system — “the House of Murphy” — that brings together different writers, producers, and directors to churn out these stories through the anthology series American Crime Story and Feud.

Murphy clearly has a savvy eye for picking the most sensational stories, with built-in audience recognition, for his revisitations. Forthcoming installments of the shows promise to delve into Princess Diana and Monica Lewinsky. Just the announcement that Gianni Versace’s murder would be the subject of American Crime Story became an event; the unveiling of the flamboyantly styled cast pictures — with Penélope Cruz as Donatella Versace and Ricky Martin as Versace’s partner — garnered the cover of Entertainment Weekly. The cast even presented an award at the Golden Globes.

But The Assassination of Gianni Versace, written by executive producer Tom Rob Smith, makes clear that promising casting, sumptuous visuals, and seemingly rich source material still can’t ensure compelling television. In order for these kinds of series to work, there needs to be some new interpretation or information brought to light that will create the kind of dramatic tension — or renewed stakes — necessary for revisiting an old story. For instance, in last year’s retelling of the Simpson saga, written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, the “trial of the century” was reimagined as a compelling tale about the very creation of stories in the judicial system and the media, and about the way America’s racial fantasies in particular influenced the public’s interpretations of the trial narratives and outcome.

This built-in device of a trial as a machine for meaning-making helped make the show. But last year’s Feud: Bette and Joan didn’t rise to the same level; the House of Murphy instead turned a mythical rivalry into an ultimately pat morality play about misogyny. Now, the story of Gianni Versace’s murder by Andrew Cunanan is similarly being mined for larger stakes, and framed as a kind of history lesson about anti-gay prejudice in the ‘90s. “The more I had read about it, the more I was startled by the fact that Cunanan really was only allowed to get away with it because of homophobia,” Murphy explained in an interview with EW. “I think it's really important to shine the light on the world FBI's largest failed manhunt and why that happened," executive producer Nina Jacobson told TV Guide; in an interview with Variety, she referenced “the neglect and the isolation and the ‘otherness’ in the way the police handled the deaths of gay men.”

But the police manhunt isn’t, in fact, a major or dramatic plotline throughout the eight episodes made available in advance, and despite the series’ title (and promotional campaign), Versace (played by Édgar Ramírez) — and his sister (Cruz) and partner (Martin) — are relatively minor characters in the show. The program’s most riveting presence, and the only major character across all the episodes, is Andrew Cunanan.

Darren Criss’s portrait of Cunanan, a queer antihero who became the object of intense public fantasy as one of the first openly gay serial killers, is often mesmerizing and always convincing. And Cunanan’s 1997 killing spree — which culminated with his seemingly random murder of Versace — certainly seems like a great vehicle for a television drama. The FBI manhunt occurred at the height of the 24-hour cable news cycle, and the coverage created a cascade of tabloid speculation. His spree started with people he was close to, with the grisly murders of a former navy officer friend, Jeffrey Trail, and David Madson, a former boyfriend. His next victim was Lee Miglin, a married millionaire Chicago real estate developer, whom it was speculated he might have met earlier through closeted gay circles. After killing a cemetery worker for a new car, he drove to Miami where he shot Versace, which created the publicity explosion that led to his infamy.

So much of Cunanan’s motives remained — and remain — shrouded in mystery, and in many ways, the gaps in his story and the manner in which they were filled in by the media after Versace’s murder is itself a compelling tale of sensationally phobic fantasies that the show could have addressed. For instance, rumors flew that Cunanan was an HIV-positive revenge killer; that he was obsessed with S&M fantasies of Tom Cruise and wanted to murder Nicole Kidman; that he had “killed for fame,” or, as one 20/20 documentary put it at the time, that he was “dying to be famous.”

Yet given how little is known about the real Cunanan — not to mention the litigiously secretive Versace family — The Assassination of Gianni Versace is, instead, awkwardly shaped around a vacuum of missing information into a respectable, unsurprising tale about gay politics. “We have these tiny points of truth, and you try to connect the tissue between them, but I would never use the term ’embellish,'” Smith explained about the challenge of filling in blanks. The show takes an omniscient perspective and fills in gaps by reducing Cunanan’s motivations to the simplest answers, and its gay characters — Cunanan’s victims — into sometimes touching but unoriginal stories about the closet.

As the Hollywood Reporter notes in its review, the show “is mostly Cunanan's story and that's unsettling, because the archetype of the duplicitous, code-switching gay killer has long been one of Hollywood's most negative depictions.” The series could have explored that stereotype itself, and how it came to guide the American public’s understanding of a mysterious and complicated figure. But in The Assassination of Gianni Versace, Cunanan’s own motivations never move beyond the caricatures floated in the ‘90s. The series seems determined to disavow its own fascination with him and imbue a potentially random murder — the titular “assassination” — with larger meaning. In doing so, it misses the chance to do something that might have been more interesting, and more dramatically effective: to look back from our contemporary perspective to parse the way that fantasy and fact melded to create the myth of Andrew Cunanan.

Despite being the show’s main character, the writers decided against having Cunanan’s name in the title because, they told Variety, it would have been “elevating him to a place we didn’t want to put him.” This attitude seemingly also affected the show’s writing, which purports to tell at least four stories through Cunanan’s murders: about the police manhunt, about the lives of Cunanan and Versace, and about the other victims. But in following so many threads, none of them are fully developed. The season starts with Versace’s murder, and works backward to show the previous murders, culminating with Cunanan’s backstory and the aftermath of the Versace murder. The episodes themselves hop around in time as well, requiring constant date reminders to keep the chronology straight.

The series opens in grand and promising fashion, with the only episode directed by Murphy, showing Versace’s world of splendor and opulence at his landmark mansion, which is contrasted with Cunanan’s shabby hotel. Criss’s creepy but lively performance is immediately captivating, and the episode sets up a potentially interesting tension in portraying Versace and Cunanan as two gay aesthetes with a talent for self-invention. Moving back in time, Cunanan’s supposed, never substantiated meeting with Versace in 1990 is presented as complete fact, and is used to give some context to Versace’s background and Cunanan’s tendency toward flamboyant embellishment.

From there, the episode moves to the police investigation, which — rather than generating suspense or showing how the portrait of Cunanan was itself filtered through the media and law enforcement — instead comes across as a narrative teaching tool for the ways anti-gay prejudice and ignorance manifested in the ‘90s. Thus, the straight officers are confused that Versace had an open relationship with his partner, who brought other men, sometimes escorts, into their bed. This isn’t used to create a mystery — we already know Cunanan is the killer — but as part of the ongoing theme of the othering of gay men and their sexuality, which is pursued even when it lacks dramatic stakes or seems irrelevant to the story.

In the subsequent episodes, the victims’ lives are turned into saintly stories about the closet or gay identity. Jeffrey Trail is depicted as dealing with the Navy’s “don’t ask don’t tell” policies, a storyline paralleled by Versace’s public revelation of his sexuality, and architect David Madson is shown coming out to his father. Some of the Trail scenes are vivid and graphic depictions of the paranoia and panic prompted by the closet, but they seem extraneous to the larger story. Similarly, after Lee Miglin’s murder, his wife Marilyn, an HSN cosmetics diva (brilliantly played by Judith Light) successfully prevents the police from leaking information that Miglin might have been sexually involved with Cunanan. The vignette is well performed and directed, but adds little to the drama of the manhunt.

The lack of mystery might have been leavened by wider insights or witty writing. But the characters’ conversations often serve as unoriginal exposition of motives that might have been better hinted at. “You loved him, but he figured you out in the end. He finally saw the real you, and you killed him for it,” Madson tells Cunanan, about why he murdered Jeff Trail. In one of Cunanan’s dreams, seemingly meant to illustrate his feelings about Versace, he says to the designer that despite Versace’s fame and money, the only difference between them is that Versace got lucky. “That’s not the only difference,” Versace replies. “I’m loved.” With this kind of pat dialogue, the show often reduces the most complex and mysterious aspects of its story to the most simplistic answers.

In contrast, during a moment when David Madson is trying to run away from Cunanan before being shot, the scene suddenly becomes a fantasy sequence in which Madson is back in the safety of his father’s home. There is a touching quality to that moment, and it suggests that if the show had leaned into that kind of acknowledged fantasy more — not using a literal dream to fill in information gaps, but to emphasize the dreamlike qualities of the story itself — it might have better matched a story for which so much is unknown.

Undoubtedly, some of the strongest writing comes at the end, when the series moves to Cunanan’s own backstory and we see him outside the context of his victims or the police investigation. Episodes that depict the gay world Cunanan moved in in La Jolla, California, are an interesting counterpoint to the usual depictions of gay men in New York or San Francisco.

In a scene from his high school years, one repeated in books and reports about his story, he sashays into a party in a red leather jumpsuit dancing to “Whip it!” He befriends an older woman supervising the party. “Can I tell you a secret?” she asks. “I’m an imposter.” He replies, “all the best people are,” demonstrating a savvy self-knowledge. There is finally an energy to the scene, freed from didactic instruction.

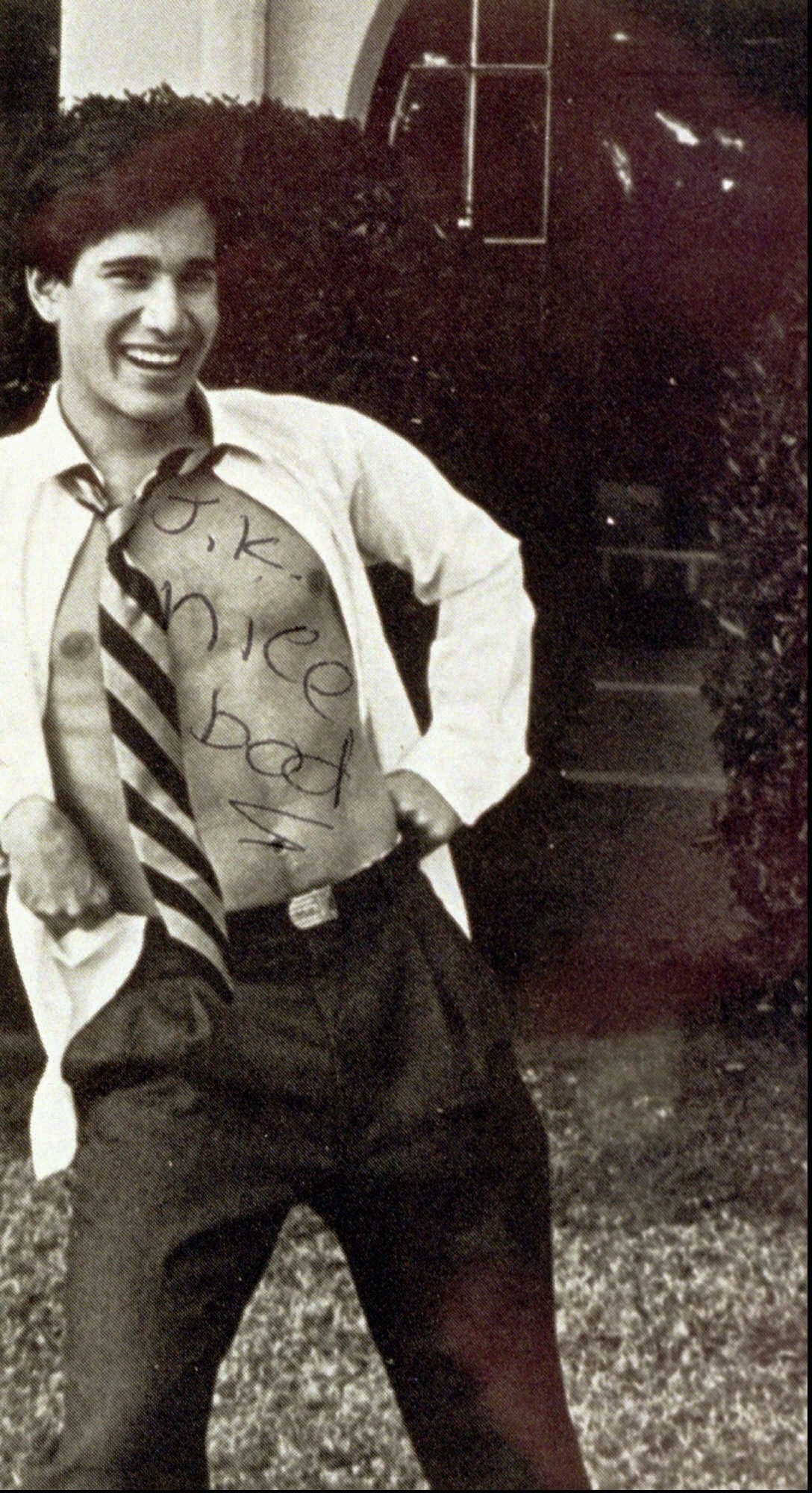

In the same episode, he takes the famous yearbook picture — reproduced in every tabloid — in which his open shirt reveals toned abs (he was voted “Most Likely to be Remembered”). It also shows his yearbook caption, "Après moi, le déluge,” (“after me, the flood”), a statement that, in real life, was retrospectively imbued with meaning about Cunanan’s self-destructiveness by a media and public hungry for narratives.

Perhaps part of the problem is that the show’s source material comes from that same hungry ‘90s media. The script is based on Maureen Orth’s 1999 book, Vulgar Favors: Andrew Cunanan, Gianni Versace, and the Largest Failed Manhunt in U.S. History, an account criticized even at the time for its lack of new insight or information, and for Orth’s own sensationalizing portrayal of the gay world Cunanan moved in, particularly the role of drugs and S&M. Much of the meaning of her reporting was better contextualized and dramatized in queer author Gary Indiana’s widely praised Three Month Fever, published the same year.

In his study of Cunanan, Indiana critiques how his life was transformed “from the somewhat poignant and depressing but fairly ordinary thing it was into a narrative overripe with tabloid evil.” And Murphy’s series might have been stronger if it had followed suit, starting with Cunanan and showing how he was reduced to that narrative. Paradoxically, though Cunanan was — as the show points out — uncomfortable about his racial identity as half Filipino and his lower-middle-class standing, he seemed by all accounts publicly untroubled by his queerness, despite growing up in the ‘70s and ‘80s. He doesn't easily fit into the larger moral lesson the series seems determined to teach, but that interesting dissonance is never fully explored.

Jacobson recently told EW that the subjects of the American Crime Story franchise must always have larger implications: “What we’re interested in is what makes this an American crime, a crime America is guilty of — not just the characters we’re exploring.” But in this case, the creators have missed their target, turning a complex narrative and character into an oversimplified vehicle for telling their viewers something most might already know. There is none of the groundbreaking genre mixing and inventive storytelling characteristic of Murphy’s greatest work.

"The most ironic thing of all," House of Murphy writer Alexis Martin Woodall said of Cunanan in an interview, "is that he wanted to be remembered and nobody remembers who he was. Everybody thinks fame is the answer and for most people, fame is totally destructive." But it’s more likely that this show will renew the wave of fascination that first turned Cunanan into the subject of books, movies, and documentaries. Perhaps it was an understandable caution of avoiding toxic stereotypes (given the dearth of thoughtful queer representation on TV), or a reluctance to romanticize a murderer, that steered the show’s writing toward a safe and respectable route. But if anything, Cunanan’s is a queer and cautionary tale about the way fame often doesn’t follow conventional morality or standards of good and evil. For that matter, neither does good television. ●