In the early ‘80s, the story of Steven Stayner’s childhood abduction and rescue riveted the nation. One December afternoon in 1972, 7-year-old Steven had been walking home in Merced, California, when he was coaxed into a stranger’s car with the promise of a ride home.

Stayner was held by Kenneth Parnell, who had previously been convicted of sexually abusing a child, in Mendocino County for the next seven years, given a new name and life, and gaslit into forgetting his family. In 1980, Parnell kidnapped another child, Timothy White. Stayner escaped, hitchhiking to the police station with White. “I know my first name is Steven,” he wrote in his statement to the cops.

The rescue story thrust Stayner and his family into the spotlight. That poignant line from his statement even became the name of a blockbuster 1989 NBC TV miniseries. Then 10 years later, in one of the most improbable twists in the annals of true crime, the Stayner name made headlines again when a string of murders in Yosemite became a national mystery. The perpetrator was Cary Stayner, Steven’s older brother.

Hulu’s Captive Audience: A Real American Horror Story revisits all these events, mostly from the surviving Stayner family members’ perspectives. Director Jessica Dimmock’s three-part series doesn’t adopt the explicitly revisionary lens that has propelled most contemporary true crime productions, which often reclaim survivors’ perspectives or reveal criminal justice failures. Instead, by foregrounding the voices of the Stayner family, including Steven Stayner’s mother, son, and daughter, it hints at themes like intergenerational trauma and the distortions and consolations of storytelling. Mostly, though, it amplifies the bizarre story’s own simple power.

Stayner’s 1972 abduction was originally treated like a local news item about every parent’s worst nightmare. His mother, Kay, had been late to pick him up at school, and instead of walking safely home, he vanished. The media covered Stayner’s disappearance at the time, and occasionally revisited it on anniversaries, but as the years went by, it seemed less and less likely that he would be found.

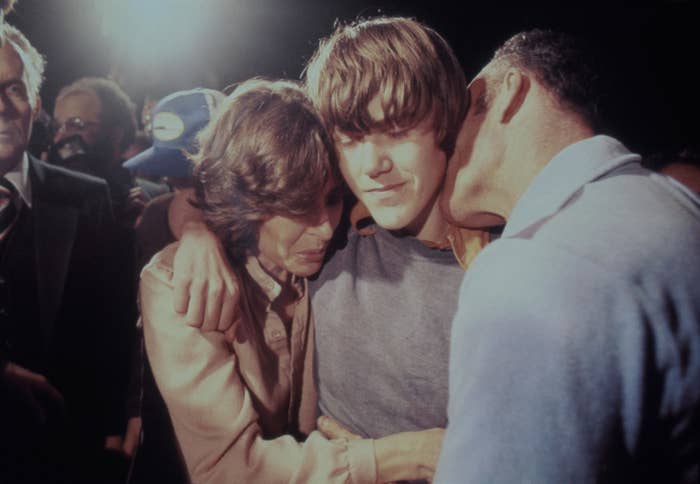

Then, after Parnell kidnapped 5-year-old Timothy White, Stayner waited until Parnell was gone one night to break out and help White avoid his same fate. When the story made the press, Stayner became a national hero. The series includes archival footage of the police press conference about White’s rescue, and of Stayner’s reunion with his family, which became heartwarming morning news content.

We don’t get Steven’s contemporary perspective on what those years were like in Mendocino; he died in a motorcycle accident in 1989. But a former classmate who attended junior high with him breaks down as she describes how he walked the halls in a hunched manner that revealed how much pain he was in. Other schoolmates recall the teenager having access to drugs and alcohol.

Without Stayner’s perspective, though, we’re mostly left to guess about what it was like being thrust into the spotlight as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. In the archival interviews we see, Stayner possesses a kind of eerie calmness. At the time, childhood sexual abuse wasn’t openly discussed in the mainstream, and Stayner’s family members also seem unable to explicitly grapple with the legacy of the abuse; for instance, Kay refers vaguely to “what happened,” and his sister, Cory Stayner, says she wished she hadn’t asked Stayner about what had happened given the gruesome nature of his descriptions.

One wonders what it was like for Stayner as local news reporters followed him around to his first day back at school after his reintegration with his family, and then covered Parnell’s trials. Still, he chose to be a consultant for I Know My First Name Is Steven. His mother says she thought it was a bad idea, but she points out that he was married by then and needed money.

The making of the NBC TV miniseries is enmeshed in both the documentary and the family’s own memories of the events. We hear tapes of the writers and director strategizing about how to tell the family’s story within the conventions of network television, and the actors who played Steven and Cary reenacting some of the scenes and transcripts with filmmakers.

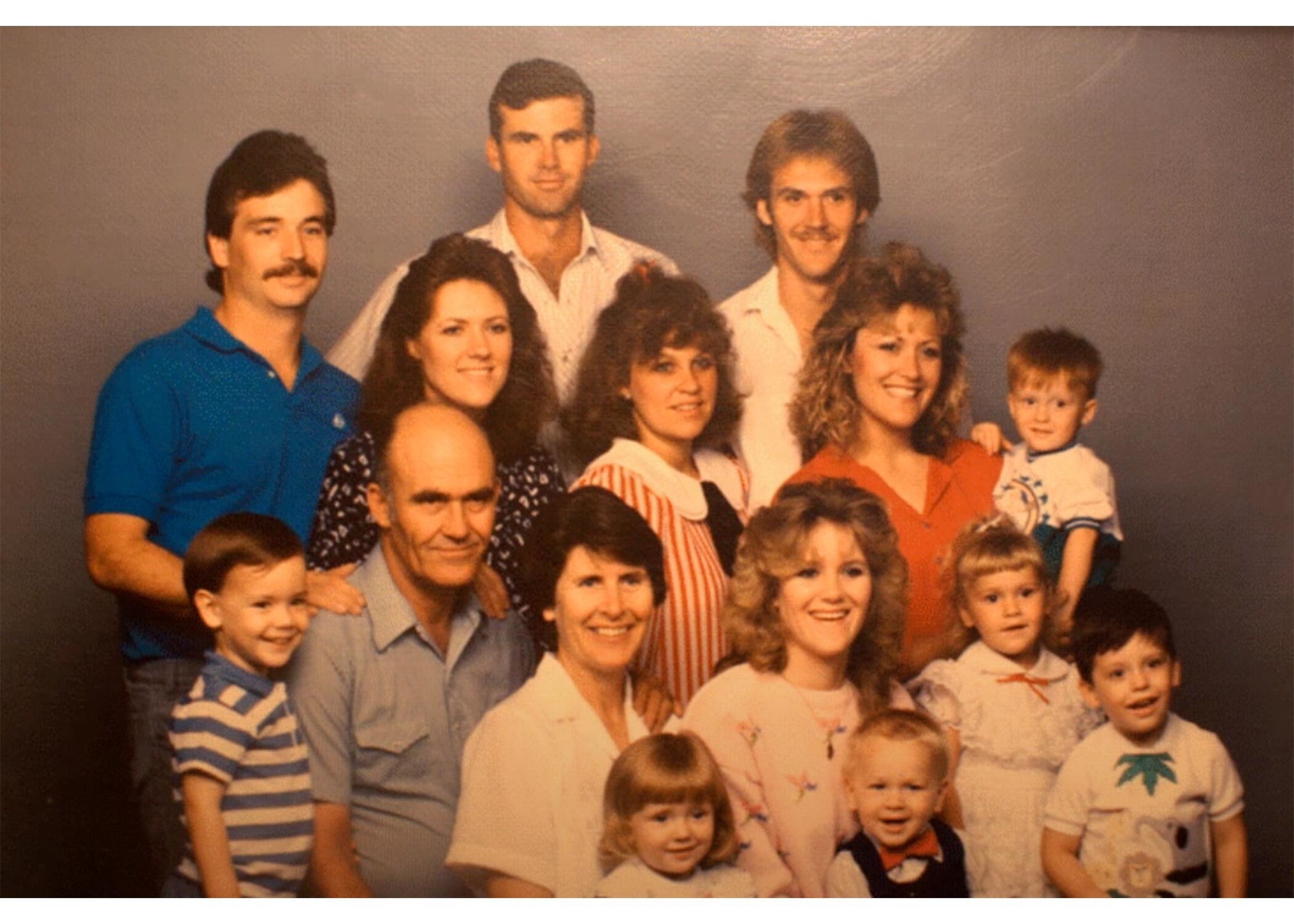

There’s a compelling quality to the actors’ renditions and the present-day reactions to the story, and the documentary’s blending of the real and the televisual highlights the artifice that went into retelling the story. Kay and Cory Stayner recall that the movie made the family more working class than they actually were, and we hear the director talk about adding drama to the story by making Stayner’s father, Del, more aloof and Kay more emotional.

The two-part series, in which Stayner himself played a cop involved in the rescue, was watched by 40 million Americans. And in the background of all this was Stayner’s older brother, Cary.

Since the advent of breakout crime podcast Serial and Ryan Murphy’s 2016 TV series The People v. O.J. Simpson, a glut of true crime content has flooded streaming platforms and podcast feeds. Captive Audience is more thoughtful than most productions. Rather than refictionalizing the Stayner family story as if it hadn’t already gotten major media coverage, grappling with their story as a media event makes for a less clichéd, more probing docuseries.

But as it turns from Steven Stayner’s story to Cary’s murders, it becomes less exploratory about existing narratives and settles into a more straightforward true crime tale.

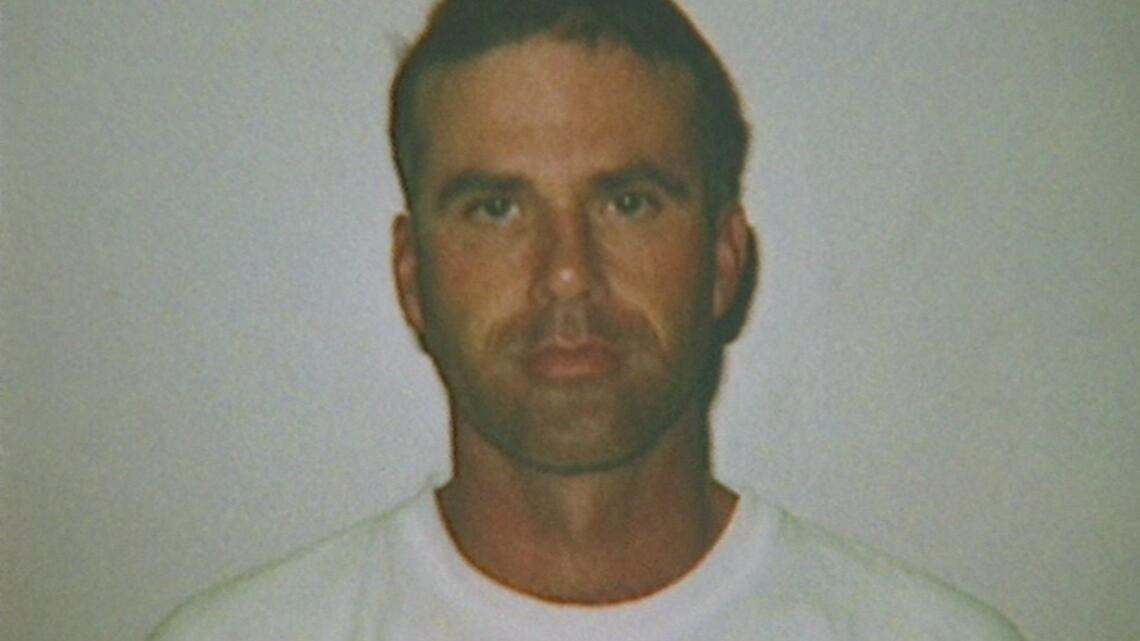

The 1999 murders of four women near Yosemite National Park were already a big story before Cary Stayner confessed in an FBI interview. The series tries to connect Cary’s story thematically to the role of media, emphasizing a reporter’s claim that Cary’s motive for the murders was wanting his own movie of the week.

Captive Audience highlights how Cary had violent fantasies about women from a very early age and includes FBI footage of Cary confessing to his crimes. Crime host John Walsh appears in TV footage talking about how serial killers might seem charming or harmless but says that “they’re very bizarre people.”

That foregrounding of individual psychopathology in explaining criminal acts is the more typical, sensationalist true crime avenue. A mitigation specialist, tasked with contextualizing Cary’s life for his defense at trial, argues that Cary was painfully shy and experienced mental health struggles. He explains that he had a record of compulsive hair pulling, nervous breakdowns, and seeking help and getting none.

Cory gets emotional as she describes how he fell through the cracks of familial or institutional care. “Cary was off — anybody and everybody who met him will tell you that,” she says. “Cary was unwell…since he was a toddler, as far as I know.” Through the more clinical emphasis on Cary’s mental health, the documentary unintentionally comments on how humdrum structural issues, like a societal lack of understanding of mental health issues or the scarcity of healthcare coverage, can often be at the root of criminal behavior.

In an onscreen exchange, Kay Stayner refuses to talk about Cary at all. In some ways, this story about the stories a family tells itself to survive gets more complicated than the documentary’s neat packaging can withstand. There was an alleged history of molestation in the Stayner family that the filmmakers don’t really touch on, which is perhaps unsurprising given the family’s extensive participation. Still, the three episodes are compellingly bound together by the emphasis on the family’s remembrances, and their experiences living in the shadow of the family lore around Steven’s story.

And in the end, it’s not so much the crimes that resonate, but Kay Stayner’s words and haunting stoicism. “I try very hard to remember the way it happened,” she says toward the end, hinting at how media stories and real life blend into each other. “I lose track,” she says. “You’re always living it, you’re always reliving it. Life takes a turn and that’s it.” ●