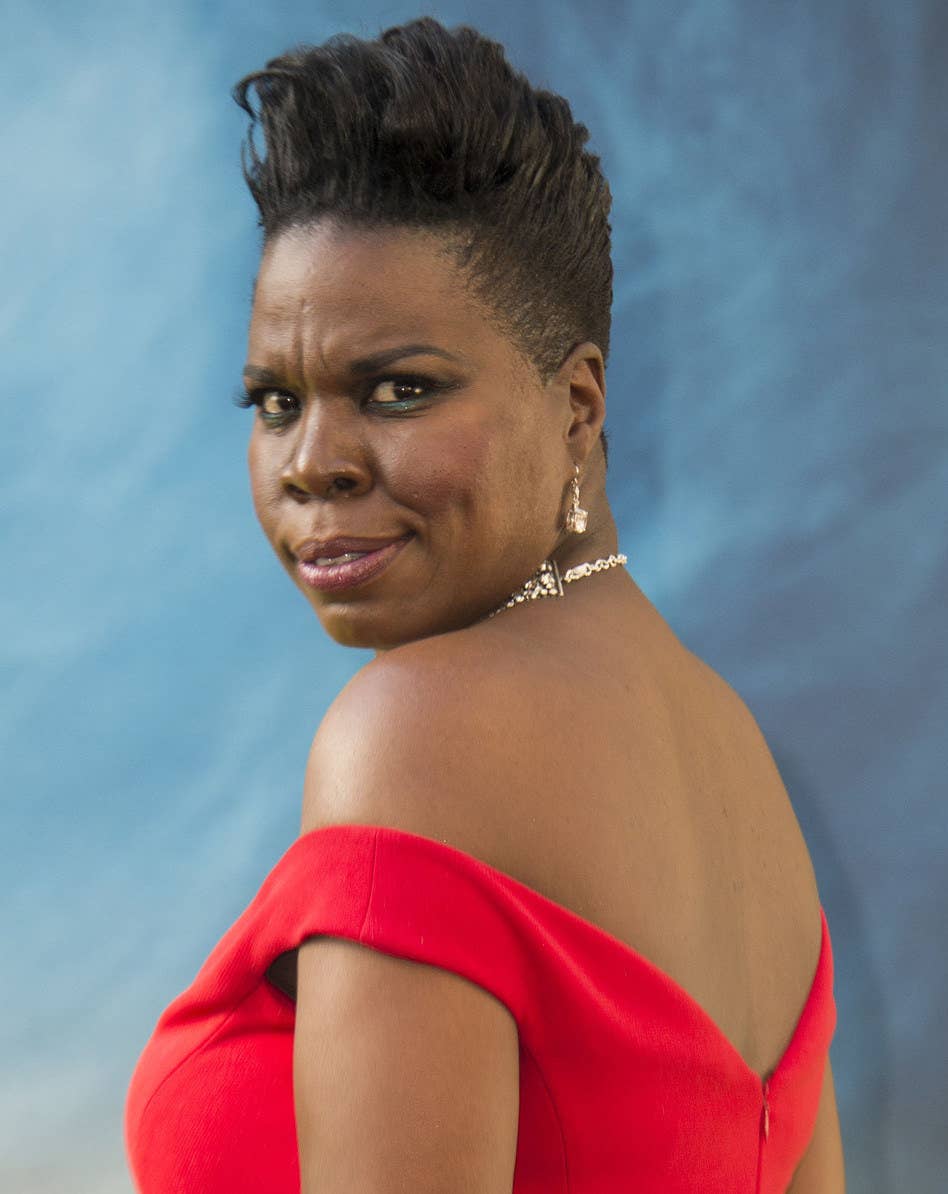

This summer was supposed to be Leslie Jones’ coronation.

Her year started fortuitously enough, with an in-depth New Yorker profile heralding the 49-year-old stand-up veteran as a woman on the cusp of major stardom, thanks to her promotion from SNL writer to regular cast member in 2014 and a coveted role as one of four new Ghostbusters in the eagerly anticipated all-female remake of the 1984 film.

Instead, as we now know, throughout the buildup to and release of Ghostbusters in July, Jones was subjected to virulent, vitriolic online abuse by a certain strain of white nerdboys apparently incensed by the fact that she was both black and a woman. Even her exuberant patriotism during the Summer Olympics couldn’t spare her from what came next: the hacking of her personal website and release of nude photos, demonstrating the nasty venom of “alt-right” trolls led by Milo Yiannopoulos, tech editor at the conservative news site Breitbart (among others). Ijeoma Oluo wrote recently in The Guardian: “professional abusers like Milo Yiannopoulos and the rest of the staff at Breitbart [are] gleefully doing their best to encourage abuse from their millions of followers who also see loud black women as a threat and a source of what they view as their denied birthright of power and respect as white men.”

Jones’ presence as a "funny black woman," perhaps the most mainstream "funny black woman" in some time, is a somber reminder of the consequences of being highly visible in a field that has never been particularly welcoming to women like her. The amount of criticism Jones received is doubly cruel considering how hard it was for her to gain visibility in the first place.

"Sometimes it feels in the industry you have to be the trailblazer, and I’m not accustomed to trailblazing. I was born in ’83."

“I have my very short American history book, which I will recite to you right now,” says Steve Rosenfield, founder of the American Comedy Institute, which counts Jim Gaffigan as its most famous alum. “It goes like this: first white men, second black men, third white women, four black women. That is the history of the United States.” Put another way, black women often benefit last from a genre of entertainment that has historically been dominated by white men—and continues to be.

But black women have been integral to the art of stand-up comedy — from the groundbreaking work of Moms Mabley (once billed as the "funniest woman in the world") in the 1960s and ’70s to Whoopi Goldberg’s genre-bending one-woman shows of the ’80s. Though as Jones’ own career has demonstrated, their breakthroughs often take longer, and they have to endure both racism and sexism in the industry.

Given black women’s history with the form, 2016 is all the more galling for the ways it has highlighted the dearth of black women in comedic spaces in recent years. Writer, actor, and producer Issa Rae’s highly anticipated half-hour HBO comedy Insecure, coming in October, makes her the first black woman to anchor a half-hour comedy on the cable stalwart since it began broadcasting original content in the 1980s. Leslie Jones was merely one of four women playing the title roles of Ghostbusters, and yet her casting was considered groundbreaking, as if Whoopi Goldberg hadn’t headlined a string of movie comedies in the ’90s.

“Part of being a black woman in 2016 is that there were people who paved that road for me, I ain’t trying to go back," says stand-up comic Naomi Ekperigin. "I ain’t trying to be one of the Little Rock Nine. Rolling up with my books and belt, terrified to walk through the door. Sometimes it feels in the industry you have to be the trailblazer, and I’m not accustomed to trailblazing. I was born in ’83.”

But in spite of Hollywood’s historically fickle relationship with them, black women are making their own way, distributing their work, stretching the boundaries of what we consider comedy, and supporting each other avidly, even as the Hollywood apparatus continues to imply that there can only be one funny black woman at a time (if at all).

Decades before Phyllis Diller and Joan Rivers were credited with leading the way for women in stand-up, Moms Mabley was a staple at the Apollo Theater, performing wisecracks from the 1930s into the 1950s and throughout the chitlin circuit, the term used to describe the theaters that catered to black folks during the Jim Crow era. Mabley, whose career has seen renewed interest because of a HBO documentary Whoopi Goldberg produced about her in 2013, was among the highest-paid black comics of the early to mid-20th century, male or female. With her gravelly voice and mismatched socks, a bowler hat and dresses in outlandish prints, she created a persona of a lecherous old woman with a penchant for younger men. Her comedy influenced Eddie Murphy, who cites Moms Mabley as a direct inspiration for his raunchy grandmother in The Nutty Professor. It certainly influenced Richard Pryor’s famous character Mudbone, the wisecracking Delta sage who claimed he was the one who told Moms Mabley to get into comedy. She made it to television in her later years, in the ’60s, where she incisively criticized segregation and the Jim Crow South.

“I went back South and people used to call me a name, Trigger. At least I think it was Trigger!”

That Whoopi was able to nab roles that were once written for white men is a testament to the social capital she held.

Other pioneers included LaWanda Page, best known as Aunt Esther on the Redd Foxx sitcom Sanford and Son in the ’70s. An old friend of Foxx, she was famous for her fire-eating on the vaudeville circuit, which she later parlayed into telling exuberantly blue jokes on the circuit. In some ways, she was a predecessor to the kind of comedy that would soon inundate late-night cable TV in the ’90s — rife with swear words, very sexual. Simply by touring on the circuit along with the men, she was a trailblazer.

In the ’80s and ’90s, Marsha Warfield (Roz on Night Court), with her icy, detached attitude, was among the few women to receive the seal of approval from legendary Comedy Store booker Mitzi Shore, according to We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy, an oral history of women in comedy. “Marsha was a brave performer,” recounted Merrill Markoe. “She would deliver a punch line, and then just stand silently and stare at the audience, deadpan. She would wait for them to laugh.” Crucially, both LaWanda Page and Marsha Warfield were able to turn their stage humor into TV careers, always the bulwark of fame and usually a major source of income for comedians who "make it."

And then there is Whoopi.

The character-driven stand-up she first performed in bars and coffeehouses in the Bay Area eventually attracted the attention of theater and film director Mike Nichols. She did a run of one-woman shows on Broadway and made such an impression that Steven Spielberg hired her to star in The Color Purple in 1985. Goldberg’s career only ascended from there. She became a bona fide movie star, eventually winning an Oscar for her performance in Ghost in 1991. Goldberg’s ’90s career is frequently cited as the gold standard for black women in the entertainment industry today. That she was able to nab roles that were once written for white men is a testament to the social capital she held.

The ’90s also brought the explicit, vulgar comedy that once made up the chitlin circuit into people’s homes via BET’s Comic View and HBO’s Def Comedy Jam, which both premiered in 1992. Perhaps the apogee of this genre of comedy, for black women, was the Queens of Comedy tour, which Showtime produced in 2000 as a corollary to the wildly successful Kings of Comedy tour, which was also filmed in 2000 and featured the likes of Bernie Mac, Steve Harvey, D.L. Hughley, and Cedric the Entertainer. Featuring stand-up from road comedy vets Miss Laura, Adele Givens, Sommore, and Mo’Nique, the film aired on Showtime but never made it into theaters, a demonstration of the tacit sexism of the industry, as The Kings of Comedy did.

Watching The Queens of Comedy now is like being privy to an intense, extremely coarse therapy session. The audience is black and largely female; the vibe is that of a revival, a celebration of black women and their bodies and their humor and their demand for sexual pleasure. “The experience was the best experience in my entire stand-up career,” says Laura Hayes, otherwise known as Miss Laura. She retired from stand-up shortly after doing The Queens of Comedy. It was the behind-the-scenes drama that did it for Hayes. Aged out of the leering sexual harassment of her younger peers, she was still subject to gender-based discrimination. “I would be the only woman on the tour and they would pick everybody up to take them to the airport and I’m sitting in the lobby of the hotel waiting to be picked. The lady behind the desk tells me, ‘Oh, they left already,’ and I’m like, how the hell they leave and not knock on my door?” she told me in an interview.

But even as black women began to make names for themselves in "urban" rooms, no current black female stand-up has been able to achieve the wide mainstream appeal of Moms Mabley or even Whoopi in her heyday. It’s this tension that is frustrating. Black women have been at the apex before, but it’s never sustained.

Comedy now, in the 2010s, is in an interesting place of transition. In some ways, it has never been a better time to be a stand-up comic. In lieu of comedy clubs — though those are still thriving — enterprising comics can mount their own stand-up showcases in bars, bookstores, and cafés. In addition to HBO, performers can clinch half-hour and hourlong specials on Netflix and Comedy Central (see Ali Wong, Theo Von, and Jen Kirkman, to name a few). The college circuit offers steady income in front of younger, more appraising audiences. Podcasts provide a medium to geek out over comedy, cultivate a personality, and if the fanbase is large enough, make money (Marc Maron and Chris Gethard have had career rejuvenations largely on the basis of their podcasts). Smaller upstart cable channels such as TruTV and TBS provide comedians with writing work, an important source of income. And the success stories of Amy Schumer, Kevin Hart, and Aziz Ansari — comics who have sold out Madison Square Garden within the past three years and possess an enviable amount of money, fame, and media attention — are also indicators of boom times.

No women top Forbes's 2015 list of the 10 most highly paid comedians; Jerry Seinfeld comes in at No. 1.

But while the barriers to entry have never been lower, the rewards have not been evenly distributed. Stand-up comedy is still overwhelmingly white and overwhelmingly male (no women top this 2015 Forbes list of the 10 most highly paid comedians; Jerry Seinfeld comes in at No. 1).

There are more ways to eke out a living in this field, but there's less opportunity to reach a massive audience as audiences grow more niche. There are more opportunities to appear on TV, but getting a TV credit doesn’t create the same impact that it used to. The late-night talk show performance–to–sitcom pipeline (if it ever really existed) is a rarity. Take a comic such as Yamaneika Saunders, who is 37 and has been doing stand-up since she was a senior in high school. She has had TV credits and was one of six cast members on the 2015 Oxygen reality TV show Funny Girls, which followed six female stand-up comics in LA as they tried to boost their careers. She was also a panelist on The Meredith Vieira Show, which was canceled earlier this year. Her humor lies pretty squarely in the Queens of Comedy tradition — she’s loud, blunt, and proudly [against] political correctness: “Being PC doesn’t mean that you’re a better person and it doesn’t mean that you’re a kinder person. You’re just a person that knows how not to put your shit out. And that’s it.” She does the club circuit in New York City and tours a little bit, and yet she has been unable to really break through. Like other comedians of her ilk, she’s plagued by a saturated market and the fact that stand-up comedy alone does not garner the fame and accolades of yore.

For some comics, such as Marie Faustin and Sydnee Washington, who host The Warm Up, one of the best but consistently underrated free stand-up showcases in New York City, stand-up is merely a means to an end. “I want to be a personality,” says Faustin. “I don’t necessarily want to be onstage every night for the rest of my life in random cities, hoping that people laugh at me. I would much rather just have a show and get paid to be me always.”

To look at the future of stand-up comedy, consider Naomi Ekperigin. A 32-year-old Harlem native who has been doing stand-up for seven years, she’s steeped in the pop culture know-how that makes her a natural fit as a TV writer for Broad City and Season 1 of Difficult People. Her stand-up adheres closely to her personality, with jokes about her white fiancé (“my Jew boo”), her favorite crime show procedurals, and her weight. She has an elastic, pliant voice that she wields to hilarious effect, coming across like a less lethal Kathy Griffin (one of her favorite comics). But she’s most interested in TV and movies. (She just nabbed her own half-hour Comedy Central special, which will air in October. It’s a stepping-stone for relatively unknown but still seasoned comics; SNL’s Michael Che and Chappelle's Show co-creator Neal Brennan have both had half-hours.) “Because there are more stand-ups than ever, you do not get paid the money that maybe you got paid during the stand-up boom of the late ’80s and ’90s,” she explains. “You perform at one of the major clubs, you get a little something, but by no means are you getting money to pay your bills.” The stand-up comic’s grind is a hustle. “I’m not old, but there are some nights I want to sit in the house. And if I can’t sit in the house because I need to go make $75 to go do 10 minutes downtown, it’s a different quality of life.”

The solution, to Ekperigin, lies in TV and film, but she wants more varied portrayals of black women in those mediums. “There’s only one conception of who this comedic black woman is. She’s large and jolly and going to put you in your place, or kind of a mother, usually asexual.” She cites the significance of Issa Rae’s upcoming HBO show Insecure. “I think Insecure is going to be great, but there should be more than one right now. Who wants that pressure?”

And so the answer, at least for Ekperigin and others like her, is to create their own avenues for this kind of artistic expression, even if it’s not strictly stand-up comedy. 2 Dope Queens, a twice-monthly live show formerly held at Union Hall and now at The Bell House in Brooklyn — which has also spun off into a podcast — is an example of this kind of thinking. The show is hosted by stand-up comic Phoebe Robinson, 31, and Jessica Williams, 27 — who's best known for her work on The Daily Show but is now developing her own scripted program for Comedy Central (Ekperigin will serve as her executive producer). It features storytellers and stand-up comics who perform on alternate Wednesdays, though Phoebe and Jessica are usually the main draw, and rightfully so. Their comedy isn’t really stand-up; it’s a lighthearted riffing between friends. The New York Times reviewed it last November, and since then, it’s become the kind of show that caters to a certain well-groomed skinny-jean-wearing set.

"You perform at one of the major clubs, you get a little something, but by no means are you getting money to pay your bills."

On the night I attended, the audience — a mix of cool twentysomethings and well-dressed middle-aged couples who had heard about the show either through the Times’s favorable review or from Daily Show osmosis — congregated in the basement of Union Hall.

The humor was mostly topical. A talk about the upcoming elections; a consensus that former Baltimore Mayor Martin O’Malley was hot, though unelectable. Robinson shared an update about her first book, which will be published in October.

People like Robinson who have achieved a modicum of mainstream success are still fighting to enjoy the kind of unspoken benefits white male comics are privy to. Robinson got her start in stand-up by taking a class at the comedy club Carolines after graduating from Pratt Institute with a degree in screenwriting.

She’s appeared on Seth Meyers and performed shows with Wyatt Cenac and John Hodgman. The latter gig was a rare example of the kind of informal networking she says male comics, especially white male comics, benefit from all the time. A few years ago, she performed at Wyatt Cenac’s birthday show in Boston alongside John Hodgman, Jon Glaser, Paul F. Tompkins, and Eugene Mirman. Afterward, there was an afterparty at a hotel. “So everyone was sitting down and there was an open seat between Hodgman and Glaser. And then Hodgman turned over and was like, ‘So, Phoebe, what’s your deal?’ I was like, ‘What?’ ‘What do you want to do with your career?’ Then he gave me all this career advice. He’s the only white male comic who has really, truly treated me like a colleague. It clarified that there is a whole other part of stand-up that I will never have access to.”

Calise Hawkins, 36, a stand-up comic who was also a cast member on Funny Girls, echoes that sentiment. “I used to hang out with a group of guys and we would all get onstage and everybody would do great; we were all funny. But afterwards, what I’ve noticed is the guys would go up to the guys and tell them how funny and how great something was and be excited to talk to them about it. And they wouldn’t come up to me and be excited to talk about something I said. They wouldn’t really care. And what I’ve realized is, guys need that. They need that, because otherwise they’ll be competitive. It’s their way of accepting each other. I don’t think they leave us out because they don’t like women, I think it’s more they don’t know that we need [that support] too.”

To combat this cliquishness, Robinson and other black female stand-ups have formed groups of their own, even passing along gigs to each other. “We’re going to build our own community, inside this very white hetero male-dominated industry that we’re in,” Robinson said. Social justice activist and former comedy club producer Agunda Okeyo hosts a quarterly stand-up showcase that exclusively features black women stand-ups called Sisters in Comedy at Carolines. “If you want to affect the industry, you should fight on the inside,” says Okeyo.

Fortunately, the tide does seem to be slowly turning in favor of more funny black women. In addition to Issa Rae’s Insecure and Jessica Williams’ still-untitled scripted series with Comedy Central, there's also Nicole Byer's starring role in MTV’s Loosely Exactly Nicole, based on her life as a struggling actor in Los Angeles. It premieres this month. What’s promising about these developments is not only that they exist, but that three different black women are spearheading their own comedic material. It suggests a movement away from the "there can be only one" narrative that dogs any disadvantaged person trying to break ground in Hollywood. The future of comedy looks more black and more female. Now, can it stay that way? •