SAN FRANCISCO — On the afternoon of April 22, Dotan Peltz, the head of sales at an Israeli surveillance company called NICE Systems, emailed his colleagues at the Italian surveillance company Hacking Team to describe an upcoming “African opportunity.”

Written in the informal, yet cryptic style used across hundreds of emails exchanged between the two companies, Peltz wrote that the “process is boiling” and that it “is being sponsored by the topmost level of the country.” Only the subject line gave away that the country in question was Uganda, while subsequent emails revealed that “the process” was a package of surveillance software for the government. The two companies had already sold software to Uganda’s police force, but they hoped that the new contract would be much larger.

Nowhere do the emails question what the Ugandan government would do with the software, despite Uganda’s frequent appearance in the newspapers that month for its surveillance of human rights organizations in the country, and attacks on local LGBT groups.

The Milan-based Hacking Team and Tel Aviv-based NICE Systems are two of fewer than a dozen companies worldwide that deal in the distribution and development of surveillance software to nation states. Hacking Team, which describes itself as a company that provides lawful interception tools for police and security officials worldwide, has been repeatedly linked to countries that use surveillance software to repress minority and dissident groups.

Until recently, the level and scope of their cooperation with NICE Systems was undocumented. But on July 8, a group of hackers leaked one million of Hacking Team’s internal emails, laying out all of the company’s secrets and explaining, in their own words, how they use malware and vulnerabilities to create spyware that can get into nearly any computer and smartphone.

The breach showed that Hacking Team and NICE exchanged nearly 3,000 emails between August 2010 and July 2015. While codenames were used in many of those emails, BuzzFeed News found at least five countries where the two companies were discussing doing business: Uganda, Mexico, Finland, Colombia, and Israel.

The contracts being discussed would provide those countries with Hacking Team's Remote Control System, which allows governments to use so-called zero days, a unknown vulnerability in software that hackers can exploit to infect the phones of anyone in their country, as well as monitor emails, record keystrokes, and snoop on their phone and computer cameras and microphones.

Spokespeople for Hacking Team and NICE declined to answer repeated requests for comment from BuzzFeed News, or give further details about the way in which their companies work together on those contracts. One Israeli employee of NICE, when reached by BuzzFeed News on a cell phone number revealed in many of the email exchanges, said, on condition of not being named, “Don’t be childish. Of course we do business with Hacking Team. We do good business with them and there is nothing wrong with that.”

“Don’t be childish. Of course we do business with Hacking Team. We do good business with them and there is nothing wrong with that.”

In April 2014, LGBT activists in Uganda began noticing that their computers and cell phones were behaving suspiciously. Phishing emails began to target the community, asking them to click on what appeared to be links to news articles, but which activist groups in Uganda later identified as malware.

“I received this link from multiple people in my mailing list, therefore it was hard for a layperson to know that it was a spyware,” one person told the Ugandan civil rights NGO Unwanted Witness. The NGO said it tested the email and found malware that appeared to be linked to the Zeus malware, a notorious piece of spyware that collects contact details, correspondence documents, and other personal information from infected computers.

“It was designed to sweep as much material from the infected computer as possible, and then use the address book to reach out to all of the contacts available through that person. It was very smart malware,” said one cybersecurity expert, who is based in Uganda and spoke to BuzzFeed News by phone. He asked not to be identified by name as he is still working to help the community and is afraid of being targeted by the government. “I don’t know who created the malware, but they were targeting this community.”

In recent years. Uganda has enacted a series of legislations that restrict access to information online, as well as personal rights to online privacy. The 2014 Anti-Pornography Act, which defined pornographic material very broadly , required internet service providers to monitor and preemptively filter and block content.

LGBT activists, meanwhile, have been fighting against a number of attempts to reinstate the Anti-Homosexuality Act, which mandated up to a life sentence for homosexual “offenses” and criminalized abetting homosexuality. The act also criminalized the use of electronic devices “for the purposes of homosexuality or promoting homosexuality. ”

Despite the act being struck down by the courts , Ugandan LGBT activists believe their computers to be monitored, and say the malware that targeted their computers on April 2014 was just one of the instances they knew of.

“This malware, the phishing emails, we found them and so we knew about them. Who knows what we can’t find? Who knows what is already infecting our computers and phones?” said the Ugandan cybersecurity expert.

No group has claimed responsibility for the April 14 malware. Email exchanges suggest that NICE and Hacking Team appear to have been already doing business in the country during that time, but the Ugandan activists groups who analyzed the malware said they had no way of telling whether it came from NICE and Hacking Team or from another surveillance software company.

Emails exchanged between Hacking Team employees show, however, that they used similar malware attacks in the past. In a July 2012 email chain, the company discusses among itself a blog post on the Dr. Webb antivirus blog about a newly discovered piece of malware. While some cybersecurity experts linked the malware to Hacking Team, the group assures itself in the email chain that the malware can’t be definitely tied back to them. “They don’t have a clue,” and “they don’t really understand what it is,” are among the reassurances sent out by various people on the Hacking Team email chain, who watch and email each other as Kaspersky and other cybersecurity firms analyze the malware and conclude it is being used by criminals on the black market.

“They think we are a new Zeus,” writes Alberto Ornaghi, a Hacking Team engineer, referring to the Zeus malware, which was well-known at the time. “It’s only positive for us,” he adds, saying that they had not discovered any other clues in the malware to point back to Hacking Team.

One quote from the blog, in particular, was highlighted by the Hacking Team CEO David Vincenzetti.

"It's unclear if the malware, which offers functionality similar to the Zeus financial malware, has been designed solely with black-market distribution in mind, or whether it might also be marketed to law enforcement agencies.”

Of all the companies with which Hacking Team corresponded, NICE appears to be their largest partner. Run by Barak Eilam, a former member of Israel’s 8200 cyberintelligence unit, NICE was acquired by the Israel-based global electronics defense company Elibt Systems for $157.9 million in May 2015.

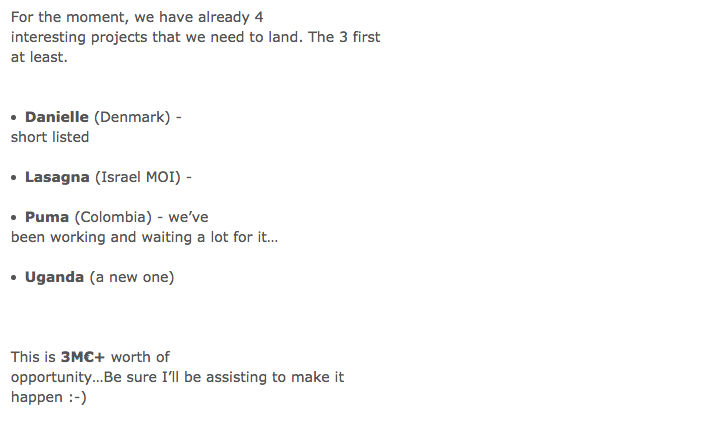

In discussing the countries on email, the companies referred to them by using codenames only, a sample for which can be seen in this email sent by Hacking Team VP of Business Development Philippe Vinci on May 13, 2015.

In the same chain, Vincenzetti writes, “Let’s use the aliases, folks!” This was just one of the mentions in which the CEO appears aware of the sensitivity in which the countries were doing business.

Email correspondence shows that NICE frequently came to Hacking Team with potential customers. India, Turkmenistan, Georgia, Brazil and other countries were discussed at length but it was often unclear which countries had active operations, and which were considering purchasing the surveillance software.

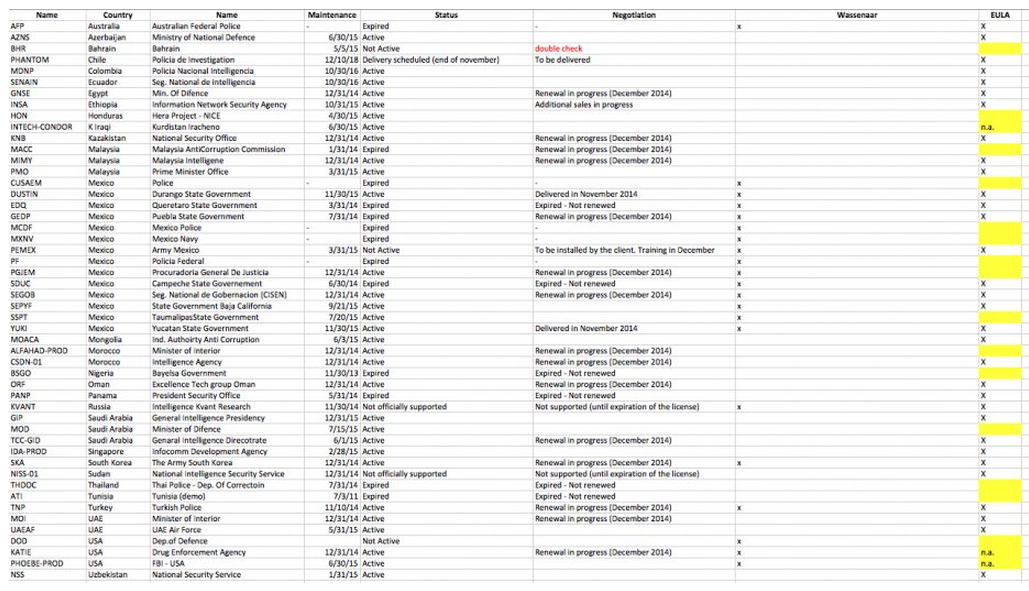

This chart, included in one of the Hacking Team emails, lists the countries in which the software is being sold.

However, other countries not included in the list also appeared to be doing business with Hacking Team, according to a review by the U.K.-based advocacy group, Privacy International.

The two companies often seemed frustrated with the pace of their collaboration, as typified in an email exchange that stretched from mid-January 2015 through May 2015 on a project code-named Puma to be based in Colombia. NICE, which had made contact with a potential customer in Colombia, had brought the project to Hacking Team’s attention. While NICE often develops its own software, it appeared to work with Hacking Team when their customers, often state police and intelligence units, wanted the aggressive malware that Hacking Team had developed that could infiltrate across various smartphones, including — as was claimed in several emails — on non-jailbroken iPhones, which are considered among the most secure phones.

In the exchange, Hacking Team repeatedly asks to be able to speak to the customer directly, after there is confusion about a document that would lay out the “scope and limitations” of the malware offered by Hacking Team. In a May 2, 2015, email, account manager Massimiliano Luppi writes, “We honestly don't understand such request. The partnership between our two companies during the last few years gave us the chance to mutually discuss why we cannot provide such information and, most important, why it cannot be given to the end user since it cannot be part of the documentation of the contract.”

“Even well-intentioned law enforcement agencies have used malware in some dangerous ways."

While Hacking Team and NICE appeared to meet often in Milan and Tel Aviv to discuss upcoming projects, they often disagreed about the way in which their contracts were negotiated. Numerous emails show the companies arguing over the wording of an end-user agreement, a document in which the companies believe they absolve themselves of any responsibility for how their software is used by having the purchaser sign an agreement stating he will use the surveillance software lawfully and responsibly.

The companies also argued frequently over pricing. In one email, in which the two discuss the price of doing business in the “Danielle” project, a codename they used for Denmark, they begin to quibble over how much Hacking Team should charge NICE. The email, sent by Luppi on May 15, 2015, proposes that for each country NICE closes a deal on, Hacking Team would give NICE a discounted price. The email states that if NICE presents a signed contract with “Puma,” or Colombia, they would receive a 15% discount. A signed contract with “Lasagna,” or Israel’s Interior Ministry, would bring an additional 12.5% discount.

“I hope this creative approach is allowing NICE to get to your requested price for Danielle [Denmark],” writes Luppi.

The answers to the email are not among the hacked emails, but as of June, the two companies were still discussing the details of those contracts. NICE, it appears, was being asked to send over more countries for potential business with Hacking Team.

NICE wasn’t the only company partnering with Hacking Team. Emails from the Italian company show they partnered with U.S. surveillance companies such as the Los Angeles-based AECOM to do business in Saudi Arabia and the Baltimore-based Cyberpoint International, with which they sold software to the United Arab Emirates. Selling through another company makes it difficult for monitoring groups to keep track of where and how the intrusive surveillance software is being distributed.

“Oftentimes we’ve seen these technologies used with little to no judicial oversight,” said Nate Cardozo, a staff attorney at the nonprofit digital rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Even well-intentioned law enforcement agencies have used malware in some dangerous ways. In much of the world we’ve seen malware used pretty clearly to target journalists and political opposition, dissidents, and others.”