Elizabeth Williams will say she doesn’t like conflict, that she isn’t usually political, but the photo from this summer looks a lot like a challenge. In it, she stands straight against a stucco wall, feet shoulder-width apart, and from behind her mask, she is staring directly at the camera. On her black T-shirt are the words:

VOTE

WARNOCK

In 2016, when a group of WNBA players became the first athletes to publicly support the Black Lives Matter movements, wearing T-shirts to their games in defiance of league rules, Williams was a newcomer to professional basketball, unsure of what to do and nervous about provoking the league’s ire.

Four years later, on that day in August, Williams was helping lead a charge to do something no American professional league’s players had ever done: endorse a political candidate.

Players on every team, across the league, were banding together in the effort to back Rev. Raphael Warnock. But no one was taking more of a risk than Williams and her team, the Atlanta Dream: Warnock was running to oust the team’s part owner, Georgia Sen. Kelly Loeffler.

“A moment like that would make anyone nervous,” Williams said. But to Williams and the Dream, there was not really a choice. Loeffler had been using the WNBA players’ decision to center their 2020 season around Black Lives Matter, and Black women killed by police, as a political prop in her Senate race. She had excoriated her own team’s players — the vast majority of whom are Black women, like Williams — and the racial justice movement.

“If she wants to play this political game, we thought, we can, too,” Williams said. “We’re college graduates. We’re not dumb here. We can strategize and learn from people. We can learn a little about politics.”

The WNBA has always been at the forefront of social justice in sports. In 2020, a year when athletes across the globe began to wield their power to fight racial injustice, the women of the WNBA pushed their power in a new direction, too.

What the WNBA players pulled off was a careful, planned political strategy. That summer, as their season began under tight pandemic restrictions in Florida, there was a crowded field of Democrats running against Loeffler with no clear frontrunners. So players from across the league came together to run their own endorsement process — a search for the candidate who fit their values.

They found Warnock, a Black man who had been an advocate of criminal justice reform, LGTBQ rights, and abortion rights. Then they put his name everywhere. Getting off the bus for their game. On the court. On their social media feeds. On the nightly news, and the front of local sports pages.

The players never spoke Loeffler’s name. But what they were saying was clear: If you want Kelly Loeffler out of office, this is your man.

There’s no doubt about it inside Warnock’s campaign: It was the WNBA players who ignited a fire for the first time, helping separate him from the rest of the field. Now, in no small part because of them, he is facing off against Loeffler in a January runoff that could decide the entire balance of power in the Senate.

Elizabeth Williams isn’t going back after this year. Nor is the WNBA. If history is any guide — and if the WNBA has anything to say about it — nor are American sports. As more and more athletes step into protest, politics, and racial justice, what the WNBA players did this summer could serve as a blueprint.

“That’s the next chapter, next evolution, of our union — for us to be more formally in a social justice — and a political — sphere. We’re going to look at what it means to be in a political space properly,” said Terri Jackson, the executive director of the WNBA players’ union.

“We’re here now,” she said. “We’re here.”

The Seattle Storm, the 2020 WNBA champions, endorsed Joe Biden and Kamala Harris in November — the first time a pro sports team had endorsed a political candidate, at least in recent memory. Ginny Gilder, the Storm’s co-owner, said the decision was entirely separate from the players’ endorsement of Warnock. But both decisions, she said, are rooted in the same place.

“There’s this fantasy that sports is in one domain and politics are in the other. If you’re a woman, a [person of color], or gay, you see that politics has always been part of how Americans view sports, and who has access to them. There’s never been an authentic divide,” Gilder said. “Certainly going forward, there’s going to be less of that.”

For WNBA players this summer, the risks of a political endorsement, especially one made against a wealthy, politically connected team owner, were especially great. But the political moment’s stakes, for a league made up of 80% Black women, were also especially high.

Before this summer, Williams, a center who was the fourth pick in the WNBA draft in 2015, had never been to a protest. But with the entire country thrown into waves of protest following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, a friend pushed her to step out and join the protesters taking to the streets.

In June, Williams posted a photo of herself on Instagram, standing at a protest in downtown Atlanta. At the time, even that seemed like a big step for her. Surrounded by signs and people, Williams holds her hands up, her clear-rimmed glasses perched on her mask.

“It was a big moment for me, as far as shifting things,” Williams said of the protest. She was nervous at first, intimidated by the National Guard and the huge crowds, even though they were peaceful.

“It was scary in that sense, but you do have all these people around you. It’s empowering. And it’s eye-opening because you feel the raw emotion that goes into it.”

Williams, though, had already been building her own political experience. In 2019, she had been a leader in union negotiations over a new contract. What WNBA players won out of those negotiations was, for women athletes, revolutionary: huge salary increases and substantial maternity benefits, a blueprint for women in sports far beyond basketball.

She and the rest of the union carried the lessons of that victory with them months later, when they negotiated a return to play amid the coronavirus pandemic. They would agree to play in a bubble, sequestered in Florida, Jackson said — but only if their season were dedicated to social justice, and only if it were centered around the issues they chose.

The players had more attention than ever before: Their games, for the first time, would all be televised on network TV. The players did not want a league-approved social justice campaign like the league- and owner-approved messages that NBA players wore on their jerseys that summer.

Players decided they would dedicate their season to #SayHerName — to the memories of Black women, often forgotten, who had been killed by the police. Every single player would wear Breonna Taylor’s name on her jersey.

Williams was a quiet, introverted force for consensus through the process, Jackson said. Then Loeffler spoke out against the team’s efforts. In a public letter to the WNBA’s commissioner, she said she was “adamantly opposed” to Black Lives Matter and called for the WNBA’s commissioner to drop its support of the movement, placing an American flag on every jersey instead. Loeffler proceeded to take the message to Fox News in primetime.

For Williams, that was the moment that everything had been leading up to.

“When our owner made a statement, it was: ‘All right, bam, this is it,’” she said. “This is our time to really step up, and all you’ve been learning, all you’ve been pushing for, this is the time to step up and say something and do something.”

She led her team to put out a statement, and Williams posted it on her Instagram with the caption, “We’ve read the letter. We reject the letter. Black lives matter. Vote in November.”

But the players wanted to do more, Williams said. Across the country, athletes were pushing get-out-the-vote campaigns and registration drives, trying to get people to fill out the census. The WNBA had been doing that too. But the players, especially those on the Dream, recognized that something else was going on with Loeffler; she was using them as a political prop, trying to boost her own campaign by going after a group of Black women.

“We didn’t just want to have a statement,” Williams said. “For everything we did, we wanted to have an action behind it.”

We are @wnba players, but like the late great John Lewis said, we are also ordinary people with extraordinary vision. @ReverendWarnock has spent his life fighting for the people and we need him in Washington. Join the movement for a better Georgia at https://t.co/yoJkjDeYy7

Sue Bird, a 20-year veteran of the league, suggested finding a candidate to oust Loeffler. What unfolded within the WNBA’s Florida bubble over the next few days was, in effect, an endorsement process. Over Zoom, players researched candidates; when they met Warnock, they grilled him about everything that mattered to them most: racial justice, abortion rights and LGBTQ rights, criminal justice reform.

“I’m not some political strategist, but what I do know is that voting is important. And I think our league has always encouraged people to use their voices and to get out and vote,” Bird told ESPN. “So what a great way for us to get the word out about this man and hopefully put him in the Senate.

“And if he’s in the Senate, you know who’s not. And I'll just leave it at that.”

Bird doesn’t ever say Loeffler’s name. Nor do Williams or any of the other WNBA players. That was the point of supporting Warnock.

Jackson watched as the WNBA players’ get-out-the-vote efforts became “a bit more pointed,” she said, zeroing in on Georgia and on the Dream. It was the players themselves who had led the messaging about Warnock.

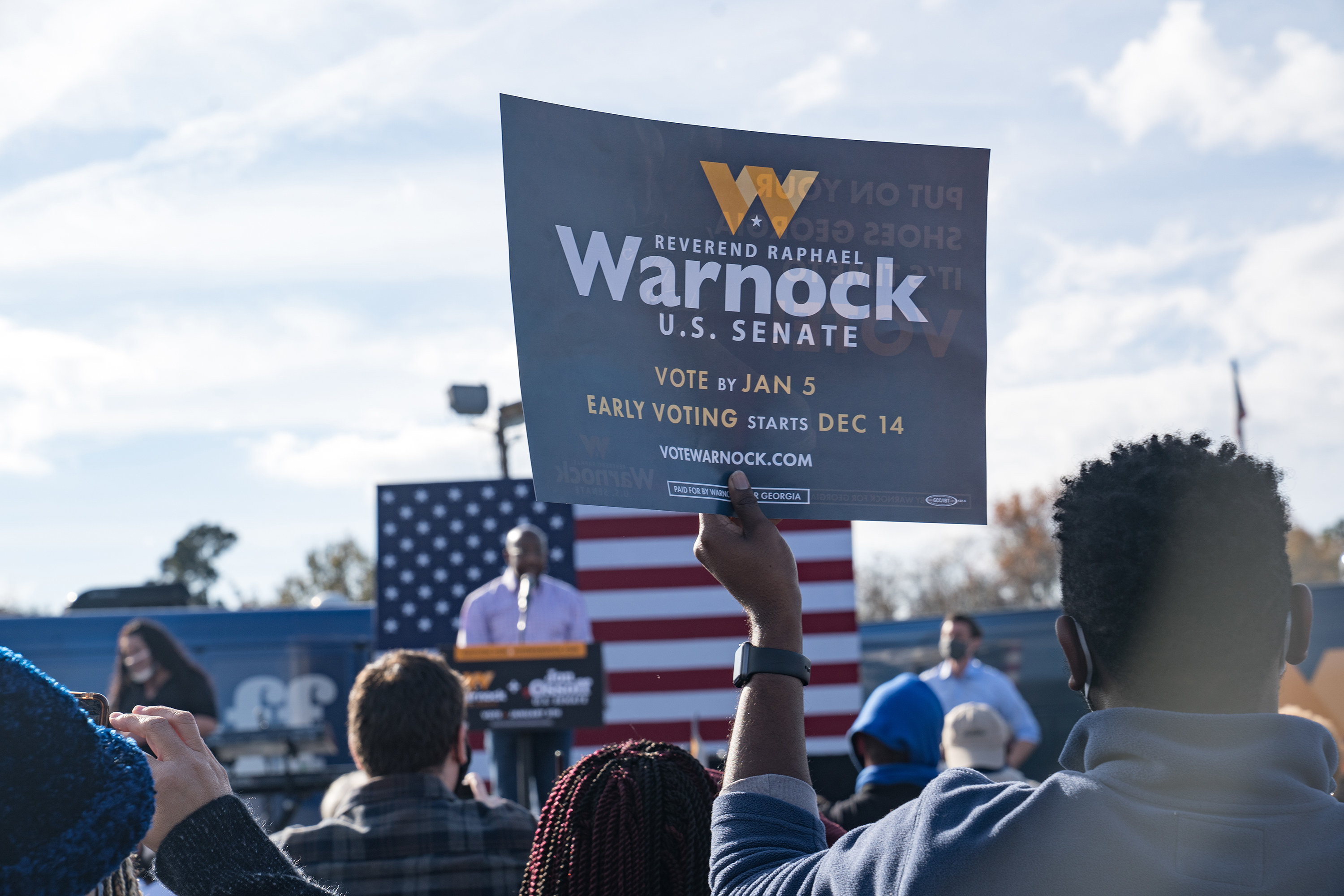

Their planning culminated on Aug. 4, when across the whole league, player after player stepped out of their team’s buses in “VOTE WARNOCK” T-shirts, resolute and unsmiling. One stopped to stare at the camera and tug at the fabric. Another held her hand out underneath Warnock’s name, as though she were modeling it.

“I popped my popcorn and sat back to watch them get off the bus,” Jackson said. “I mean, never has there been so much attention on players getting off a bus.”

Williams felt anxious that day, especially for her team. But, in a way, it was a lot like that protest in downtown Atlanta she had attended that summer. They were all together. The moment felt to her like something that the whole league had been preparing for for years — long before 2020.

The Warnock campaign felt the effects immediately. It saw surges in grassroots donations and Twitter followers that it had never experienced.

It was the timing of the WNBA’s support that truly mattered, one analysis found. In the contours of the Senate race in Georgia, what the players did was profound. Warnock had been mired in a crowded field of Democrats. But in August, after the WNBA players picked him out of that field, elevating him as their candidate of choice to take on Loeffler, his poll numbers started rising. By fall, he was the clear Democratic frontrunner. In November, he won more votes than any other candidate, setting up the Jan. 5 runoff with Loeffler.

Most WNBA players are abroad now, playing in foreign leagues as they do almost every offseason. Williams is in Turkey. But the players have been doing what they can from across time zones. And when they get back to the league next year, things are not going to go back to the way they were.

The core of the WNBA’s racial justice efforts — protest, and collective action — isn’t going anywhere. And Williams wants to help lead them. Later in the season, after a Black man, Jacob Blake, was shot in Kenosha, Wisconsin, the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks announced they would not play their game, setting off a daylong work stoppage in the middle of the playoffs.

The WNBA’s pair of games had been scheduled to start within hours. As the players debated what to do, Williams sat listening, jotting down what everyone was saying. For women players, the decision was different: They did not have the lucrative endorsement deals and million-dollar salaries that men did, and their chances in the spotlight to play nationally televised games were far less frequent.

But the WNBA players decided that they too would make the decision not to play, using the spotlight to talk about Blake and Black Lives Matter. By then, Williams was ready, a speech mostly written.

There were other players who had been more prominent within the league’s racial justice fight — but given everything that had happened with the Dream that season, there was no question of who should give the speech, Jackson said.

“In that moment, it needed to be Elizabeth.”

Williams was nervous, again, as she stood on the court to speak on behalf of the league, her voice wavering slightly as she glanced up and down from her phone.

“If we wait, we don’t make change,” Williams read. “It matters. Your voice matters. Your vote matters. Do all you can to demand that your leaders stop with the empty words and do something. This is the reason for the 2020 season. It is in our DNA.”