TIJUANA, Mexico — It was a chilly spring evening and the dining room at Misión 19, one of Tijuana’s many acclaimed restaurants, was buzzing. Waiters patiently talked diners through the menu — would the tiger milk shrimp with aioli be best paired with a red wine from the nearby Guadalupe Valley, or perhaps a mezcal-infused cocktail?

Nearly half the diners were from across the border, having driven down the San Diego expressway before settling in to enjoy the food created by superstar chef Javier Plascencia. A smattering of luxury cars could be found parked several floors below Misión 19, which sits on the second floor of a sleek, glass-enclosed building in the city’s business district.

A couple of years ago, when Anthony Bourdain was asked to recommend a good restaurant in San Diego, he suggested avoiding the city altogether and heading down south to Misión 19 instead: “No disrespect to San Diego, there’s a lot of great restaurants here, a lot of really fine restaurants. I personally would drive over to Tijuana.”

Bourdain might have been slightly ahead of the curve, but the restaurant is one of many signs of a major boom in Tijuana, a city that has long been looked down upon as a grimy playground for visitors from the U.S. In the Prohibition era, Tijuana was popular with gamblers who wanted a place to drink while they played; during World War II, soldiers based in San Diego came here to visit the local brothels; more recently, American students have known it as the perfect place to go and get high. From the so-called donkey shows (an urban legend involving a Tijuana prostitute and a donkey) to the Tijuana Hooker drink (“a shot of crappy well tequila with a half-shot pickle juice chaser,” according to a Phoenix New Times recipe), it has long been the subject of mockery north of the border.

For decades, Tijuana was also the stronghold of Mexico’s powerful Arellano Felix cartel, which controlled the flow of cocaine, marijuana, and other drugs through the city and into the U.S. A turf war exploded a decade ago as other criminal groups tried to gain access to the highly coveted drug corridor, and bodies stacked up on the streets. Many residents in the city fled as the military descended in an attempt to re-establish order.

But that is all changing. Within walking distance of Misión 19 is the upscale Cacho neighborhood, where CrossFit studios, fancy food trucks, and eco-friendly dry cleaners have sprouted in spaces that were either abandoned or nonexistent less than 10 years ago, breaking up the monotony of the otherwise nondescript buildings lining most of the city’s dusty hills, home to 1.6 million people.

Some of these places are being filled by shared working stations, where companies like Uber and Yelp have set up offices. In Empleados Federales, a neighborhood that housed customs employees in the 1940s, you can find a mixed-use space called Estación Federal, which houses a farmers market selling artisanal beers, a minimalist art gallery (recently featuring a gold mustache-wearing Mona Lisa), and exposed-brick lofts for rent.

Going for as little as $450 a month, the lofts are “a plausible solution to the outrageous cost of living in San Diego,” Miguel Marshall, a talkative entrepreneur leading the change in Tijuana, wrote on his Facebook wall. To make the point, he posted a story about San Diego’s average monthly rents hitting $1,618.

It’s here that the American Dream collides with reality. Americans priced out of their home cities are now heading down south to set up in Tijuana, but there are plenty of Mexicans here who have already discovered that the U.S. isn’t an easy place to make a living. That’s because, alongside its new arrivals from north of the border, Tijuana is also home to thousands of Mexicans who were deported from the States, forming an underclass in a city that is trying to shake off its old image. For many Americans, Tijuana is a new land of opportunity; for the Mexican deportees, it is a return to an unwanted past.

While gentrification stalks neighborhoods across the world, from Brooklyn to the East End of London, in Tijuana it’s almost an official policy. The most vulnerable deportees are being erased from the streets, as part of an operation to clean up what many here see as an eyesore that risks putting off the incoming entrepreneurs and young professionals.

“The public policy is to help [deportees] with a sandwich and a phone card while hiding them, hiding the problem and pushing it out of sight,” Marshall said.

When the green pickup truck drove up to El Desayunador Salesiano del Padre Chava, a soup kitchen near the border with the U.S., a group of men instantly crowded around it, begging its driver to choose them for a day job.

José Hernández stared at the scene, aware that he was too old — 55 or 60, depending on when you ask him — and too frail to be considered. In any case, Hernández, who had just wiped his plate clean at the soup kitchen and stuffed a leftover muffin into his jacket pocket, wasn’t there to look for a job.

It’s that cops don’t harass vagrants near the the soup kitchen, which is staffed by migrant activists, he said. “This is the only place where policemen respect you a little bit,” Hernández said, revealing a smile missing most of its teeth. When he extended a hand to take a cigarette a friend offered him, a bright red handwritten “229” stood out through the veins on the back of his hand. It was visible among a series of other numbers scrawled one on top of the other — each represented a visit to a soup kitchen.

Hernández — nicknamed “El Jarocho,” as people from Veracruz state are known — spent much of his childhood at the beach conning tourists into making a wish as they threw coins into the ocean, which he would later collect. When he was 7, he took a train up through Mexico and eventually settled in California. Hernández took several jobs over the years, as a maintenance boy at a Motel 8, a driver at a home for cancer patients, and a car mechanic. He was deported several times, he said, once for not carrying an ID, another for trespassing on private property.

He can’t remember how long he’s been back in Tijuana this time around, but says he hasn’t seen his daughters, who live in California, for at least seven years. “They are a different class of person,” said Hernández, who like many deportees has few ties left to Mexico after years abroad.

The streets Hernández lives on are nothing like the upmarket heart of Tijuana. He makes his way from soup kitchens to odd jobs, walking past hand-painted signs advertising car shops, beneath makeshift living quarters. When a man pushing a cart filled with plastic bags crossed paths with Hernández, trailing the pungent smell of urine, both kept staring straight ahead. Electricity wires hung uncomfortably low above the sidewalks.

“Not this street, keep walking,” he said quietly, heading a block over.

If Hernández knows anything, it’s on which streets he’s most likely to get shaken down by cops, running the risk of being thrown in jail. So he chooses his route carefully, avoiding the richer blocks, zigzagging around a confined area of Zona Norte, a neighborhood that includes the city’s red-light district, which has one of the highest rates of human trafficking in the country, according to Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission.

A 2013 study by El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, or Colef, a research institute in Tijuana, revealed that 93.5% of deportees surveyed had been detained at least once during the previous two weeks, while 70% had been detained at least twice. The reasons, the study found, were often that they were simply loitering, or not carrying an ID.

Sitting inside the Juventud 2000 migrant shelter, Hugo Cleofas played with a laminated ID made for him by the director of the shelter. A cook from the state of Mexico, Cleofas, who can often be seen wearing a red apron in the shelter’s kitchen, said he had lost count of how many times he’s been picked up.

One day, Cleofas was late to work and started running along Calle Coahuila, known for its strip clubs, when a cop stopped him and asked whether he wanted to take a holiday to a local prison or hand over whatever was in his wallet. He chose the latter, he said, and missed work because he couldn’t pay for the bus.

Outside on the streets, Hernández said he avoided Calle Benito Juárez 2nda, the street next to the Desayunador, because police officers congregate there to pick up the city’s homeless. Instead, he walked one block over to Calle Carrillo Puerto (known as Tercera), hands in his pockets, trying to draw as little attention as possible.

On Tercera, Hernández — who usually sleeps on top of discarded boxes in the parking lot of a funeral home alongside a group of friends with nicknames like “El Taliban” — pointed at different auto repair shops where he has either lived or worked.

After a few blocks, he walked into one of the shops and toward the back, where his pet dog lives. Lobo, a blonde mutt who was chained to the wall, started yelping when he saw Hernández, who knelt down to wrap the dog’s paw in his hand.

“He’s wild,” said Hernández of Lobo, “but when you treat him kindly he becomes noble.”

One night in early March 2015, police and firefighters descended on the area known as El Bordo, the concrete embankment separating Mexico and the U.S., sweeping people out of their makeshift homes. No one knows for sure what happened, but three former residents of El Bordo repeated similar versions: Uniformed men threw burning tires and gasoline into the settlement, “forcing people to scurry out like rats,” according to one deportee, who spoke on condition of anonymity, out of fear of reprisals from the police.

Migrant activists in the city confirmed that they saw several people from El Bordo with burns to their skin.

Whether or not the fire was started by authorities, many people were relieved to see the deportee community kicked out of El Bordo. “We demanded that they be removed,” said Francisco Villegas, the president of Tijuana’s Tourism and Conventions Committee. “This is the image not just of Tijuana but where Latin America begins,” he said of the drainage canal that housed hundreds of vagrant migrants and is the first thing visitors from San Diego see as they cross the border. Today, rather than a tent city of homeless people, visitors are more likely to see couples strolling, or joggers out in the early evening.

It is no surprise that for years El Bordo drew hordes of deportees; according to the National Migration Institute, Tijuana received more deportees from the U.S. than any other Mexican city along the border between 2003 and 2011 — more than 1.1 million during this period.

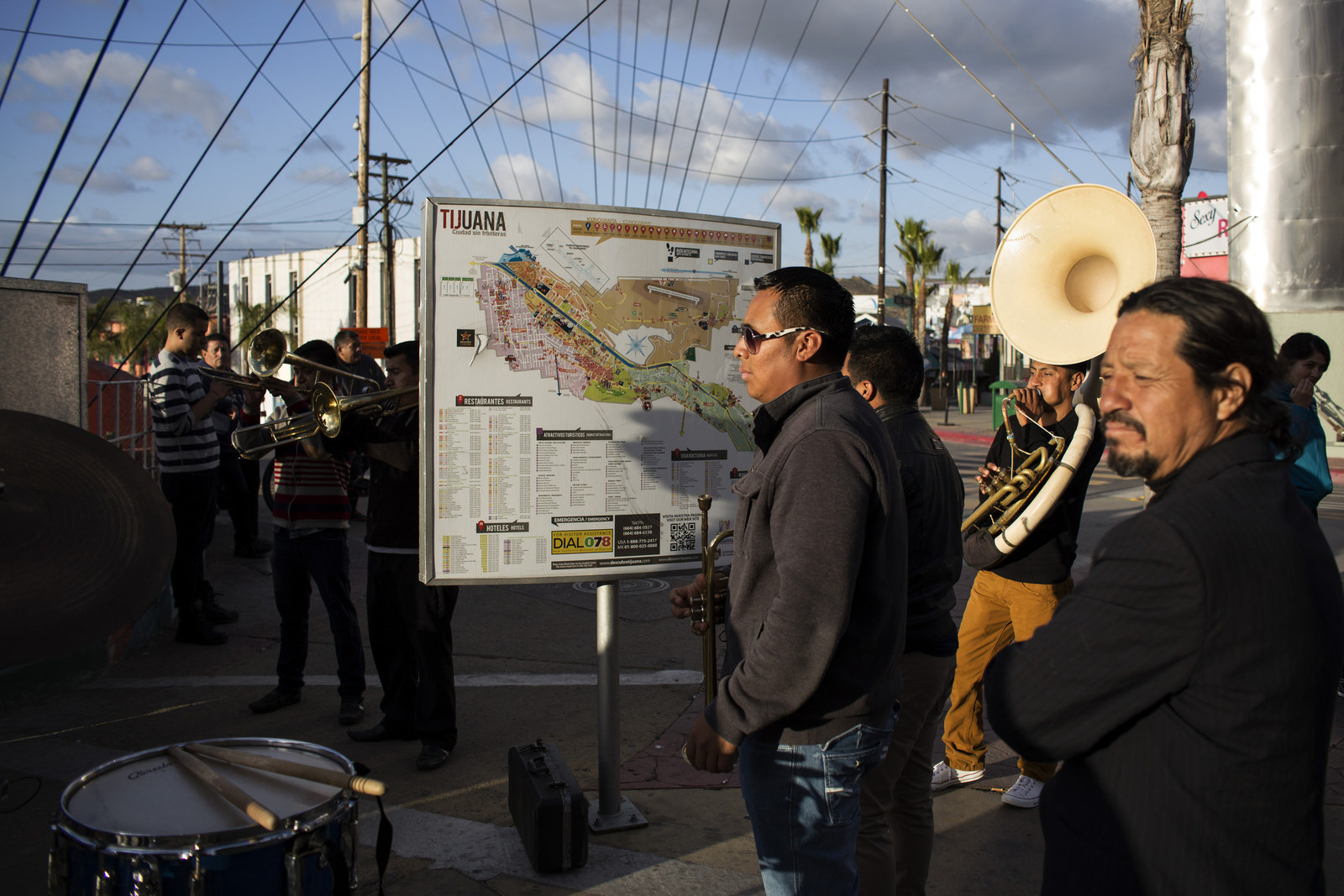

They were dropped into a city they barely knew, disoriented by its hilly skyline and oblivious to the kitschy charm that has drawn millions of Americans for years, like the photogenic zonkeys — donkeys painted with zebra stripes — on Tijuana’s main drag.

Hundreds of deportees settled under plastic tarps in El Bordo, in sewers that discharge into its shallow river or in one of about 25 claustrophobic holes dotting the pavement. Most were waiting to make another attempt to cross the border. Many, however, became hooked on meth or heroin and stayed permanently.

Despite their downward spiral, many of the people living in El Bordo were often just as educated as the rest of Tijuana’s population. The Colef study revealed that nearly 1 in 4 of El Bordo’s approximately 1,000 residents had a high school diploma and more than half spoke English.

“This is a huge potential for Mexico,” said Father Jesús Arambarri, who is in charge of the Desayunador, the nearest soup kitchen to El Bordo. “Many have professions that don’t even exist here yet,” he added, explaining that some regulars there are familiar with rare auto parts and have experience with much larger construction projects than those in Tijuana. Inside, volunteers from a local high school ushered in sleepy-looking men, squeezed disinfectant onto their palms, and served them coffee.

Many of the deportees who were evicted from El Bordo were taken to rehab centers in nearby cities like Tecate and Mexicali, beaten up, and forced to work for no pay for several months, at least three men who say they escaped from these programs told BuzzFeed News during separate interviews. Many have not been seen since. According to local reports, those who stayed behind initially wandered around the Zona Rio, where Misión 19 is located, but they ran the risk of being picked up by the police.

Tijuana’s secretary of public safety did not grant BuzzFeed News an interview to discuss this and other police practices in the city.

El Bordo was “a very denigrating image not just to Tijuanenses but also to visitors who crossed the main pedestrian bridge into Tijuana,” Tijuana Mayor Jorge Astiazarán told BuzzFeed News. He added that life in El Bordo was “a vicious cycle” of crime and drugs and that evicting its residents was “something that was supposed to have happened years ago.” Astiazarán, a doctor by training, agreed that the resources available to deportees were insufficient.

At one point during the interview, his spokesperson Jesús Velasco interrupted to suggest the conversation shift to more positive topics.

And this is what worries activists in Tijuana: In an effort to bring in investment and to gentrify the city, the most vulnerable people are being punished. What happened to the people of El Bordo “is about human waste, about those who don’t matter, those who are not part of society,” said Laura Velasco, an investigator at Colef.

In January 2007, then-President Felipe Calderón sent around 3,000 soldiers and federal police officers into Tijuana; the city had been ravaged by violence for decades, with powerful cartels vying for control of the drug corridor into the U.S. Calderón had only been in charge for a month, but his policy of breaking up criminal organizations and tackling corruption saw all local police in Tijuana disarmed.

With no trustworthy cops and a raging confrontation between drug cartels vying for control of the city, Tijuana hit rock bottom by 2009: 700 of the 1,000 businesses along Avenida Revolución, the main roadway in the city, had closed, said Villegas. Insecurity, the outbreak of H1N1 flu, and an economic recession in the U.S. contributed to the city’s decay, he explained.

It is hard to get an accurate homicide rate for the city; according to the National Statistics and Geography Institute, or INEGI, there were 1,256 homicides in 2010, one of the most violent years there, while Tijuana’s Public Safety Secretariat reported 688 homicides during that period.

“For many years Tijuana lived like a black legend,” Astiazarán said. “It’s taken a lot for us Tijuanenses to clean it up.”

But they did. Homicides dropped to 516 in 2011, according to INEGI. Kidnappings were slashed by more than half between 2010 and 2014, while robberies fell more than 30% during that period, the Public Safety Secretariat reported. The city, virtually everyone here agrees, started to feel safer all around.

Part of the reason for the drop in recorded homicides is that warring cartels have evolved, according to Adela Navarro, general director of Zeta, a weekly investigative magazine in Tijuana that focuses on cartel violence and corruption. Cartels have changed their strategy, choosing a “low-impact approach,” killing enemies inside their homes or on the outskirts of the city rather than in public spaces. Their targets are no longer “big fish,” she says, but low-profile residents, like street food attendants.

As people began to emerge from the anxious haze they lived in — or fled from — ties with Tijuana’s sister city of San Diego began to grow. Last year, a group of American and Mexican investors opened a 390-foot-long bridge connecting the Tijuana International Airport to San Diego.

But not everyone is convinced that Tijuana has really left its past behind. Navarro says that violence still bubbles under the surface.

“It is a false calm,” Navarro said, noting a recent surge in homicides. There were 123 homicides in January and February, more than twice the number recorded during the same period last year. She warned that the government has been underreporting homicide figures by 20 to 30%.

The team of journalists at Zeta who keep count of murders in Tijuana spend many of their days holed up in the dimly lit newsroom, housed in a bunker with double-enforced walls on a quiet street. Behind the blinds in Navarro’s office, which she always keeps drawn, is a bulletproof window.

The paranoia is warranted: In 1988, the magazine’s co-founder Héctor Félix Miranda was gunned down (every issue of Zeta now devotes an entire page to him), and seven years later, its other founder, Jesús Blancornelas, was nearly killed in an ambush.

Navarro said the recent arrival of a new cartel called Jalisco Nueva Generación was likely to unleash a new wave of violence as the Sinaloa Cartel, famously headed by Joaquín Guzmán, known as “El Chapo,” tries to maintain control over the city.

“Tijuana is sitting on imminent danger,” she said.