In October 2014 I came across a false story that was quickly racking up likes, shares, and comments on Facebook. The article, published on nationalreport.net, claimed an entire town in Texas was quarantined after a family contracted Ebola, and it used a fake quote attributed to someone at a Texas hospital to pass itself off as a real news story. I warned people about what I was seeing:

Fake news site National Report set off a measure of panic by publishing fake story about Ebola outbreak: https://t.co/CHrjtpUhyc Scumbags.

That tweet was one of the first times I publicly used the term “fake news” to refer to completely false information that was created and spread for profit.

By then I was running a research project and associated website that tracked and analyzed the spread of misinformation on social media and in the news. I kept encountering sites like nationalreport.net and began calling them and their content “fake news.” It seemed like a natural description; I didn’t put a lot of thought into it. Over time I played a role in helping popularize the term.

That was 2014. Here’s where we are now:

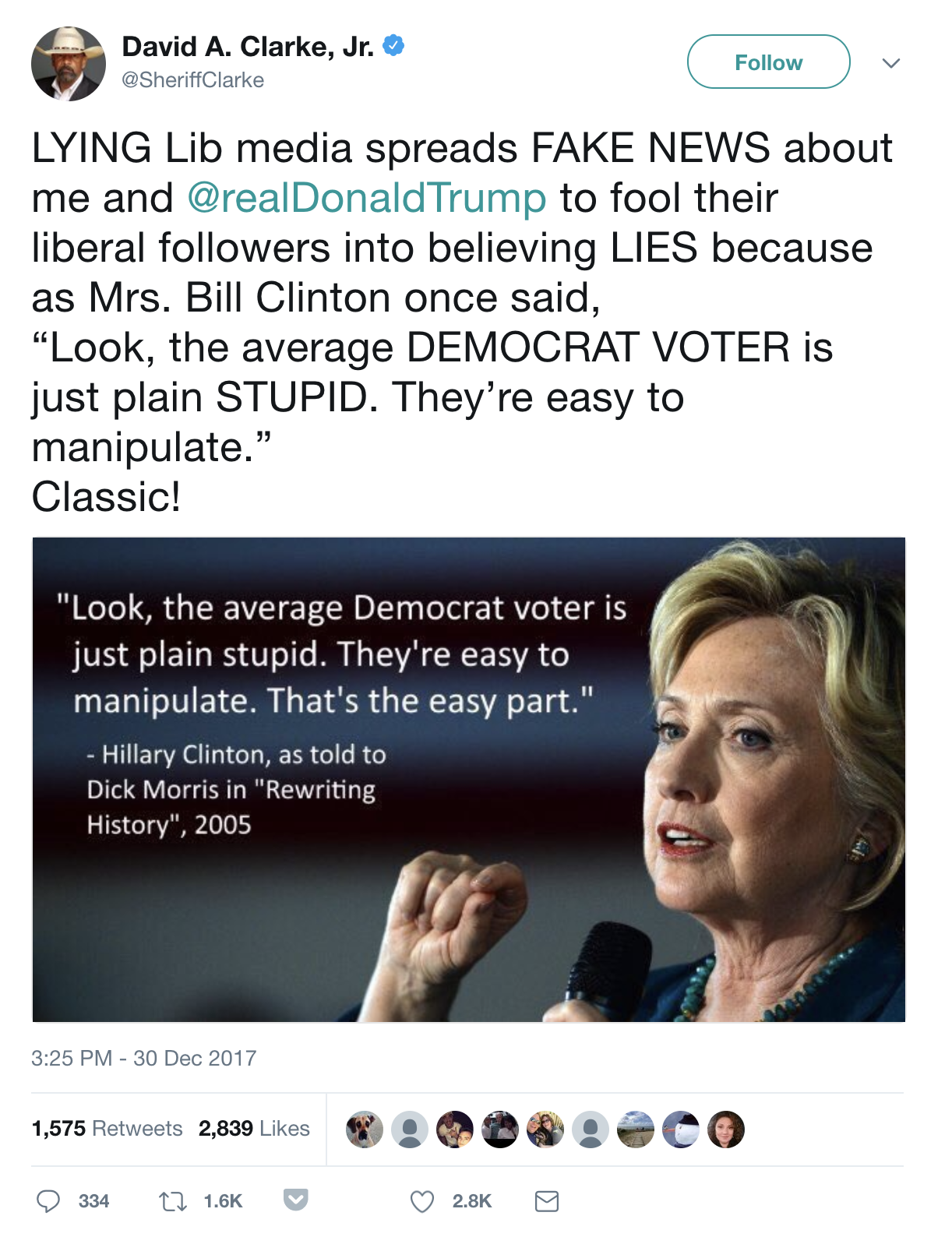

Perhaps nothing illustrates what’s happened to the term “fake news” over the past year better than that tweet, from prominent Trump supporter David A. Clarke Jr. In just a few words, he labels reporting on verified court documents about him as fake news and presents a completely fabricated Hillary Clinton quote as real, all while painting the media and liberals as too dumb to recognize the truth.

Three years after that tweet about National Report, I cringe when I hear anyone say “fake news.” Yet thanks to my work on the subject, I’m inextricably linked to the term. (This isn’t bragging: In fact, to some it’s an indictment. “How BuzzFeed Editor Craig Silverman Helped Generate the ‘Fake News’ Crisis,” read a Breitbart headline from almost exactly a year ago.)

Ironically, I started doing this work in criticism of the mainstream media: tracking incidents of plagiarism and fabrication, publishing annual lists calling out the errors and apologies of the year, and pestering editors who refused to explain what happened when major errors took place in their newsroom.

The press still gets a lot wrong, and that certainly includes the coverage of the Trump administration. (Put me squarely in the corner of those who think CNN and other outlets need to disclose much more about how they and their sources completely botched a report about when the Trump campaign learned of WikiLeaks’ cache of DNC documents. The same goes for the retracted Fox News story about Seth Rich.) But it’s possible — and essential — to delineate between errors made in the course of actual reporting and people or entities who consciously lie for profit and propaganda. Yet, today, any form of media mistake is weaponized, with willful fabrications treated the same as sloppy errors.

A functioning press and democracy require criticism, transparency, and consequences for journalistic mistakes. They also require that we’re able to collectively distinguish them from lies and deception. Otherwise, as the former sheriff's tweet showed, real information will be painted as fake, and manufactured bullshit gets presented as fact.

Back when I encountered that fake Ebola story and others like it, I started building a list of the sites publishing exclusively false stories engineered to go viral. In 2014 I had identified about a dozen of these sites. (My 2017 list, which you can download here, has 167.) These sites peddle misinformation for money, and even back in 2014 they were doing gangbusters business thanks to Facebook and ad networks.

Then, as now, the success of this form of misinformation revealed how our media environment is more easy to manipulate than ever before. Fake news was a canary in the coal mine, but it’s by no means the only example of what some now label “information disorder.”

It became my beat and obsession to track these sites, expose who was running them, and to sound the alarm about what was going on. I wrote about Canadian teens earning money from Justin Trudeau hoaxes, the man behind that fake viral “Pope endorses Trump” headline, a comedian scoring viral hits with outlandish fake crime stories, and a network of websites propagating false news articles about terrorist attacks in cities around the world, among much more. And, of course, I wrote about those Macedonian teens who later became the poster kids for fake news. I (perhaps naively) assumed that there could be a sense of unified outrage and action about this issue.

After the election, fake news became a topic of concern and debate. My stories looking at viral fake election news posts and the Macedonians article achieved their own measure of virality, with the latter even ending up on Obama’s desk. But in retrospect, this is where the problem started. Fake news could not survive contact with the hyperpartisan world of the mid-2010s.

I should have realized that any person, idea, or phrase — however neutral in its intention — could be twisted into a partisan cudgel.

I should have realized that any person, idea, or phrase — however neutral in its intention — could be twisted into a partisan cudgel. I had always reported on fake news generated from both the left and the right. But after the 2016 election, shocked US Democrats, looking for explanations, adopted the concept as an easy answer to the puzzle of Donald Trump’s election. And in response, Trump and his supporters saw the term as a threat and an insult — and a weapon.

The end of “fake news” as I knew it came on Jan. 11, 2017, when Donald Trump — master of branding — redefined the term to mean, effectively, news reports he didn’t like. The previous day CNN and BuzzFeed News had reported on the existence of the Steele dossier.

Trump stood on stage during his first press conference since Election Day and pointed his finger at CNN’s Jim Acosta. “I’m not going to give you a question — you are fake news.” (He also called BuzzFeed a “failing pile of garbage.")

In that moment, fake news was conscripted to fight in the partisan wars, and was co-opted by Trump. This instantly made it harder to win the actual fight against the manipulation of platforms for profit and propaganda, the real challenges facing democracy in a connected age, and the risks of censorship from platforms and governments alike.

Political movements around the world recognized the genius of Trump’s tactic and adopted it. Now, “fake news” is a global phrase uttered by leaders and citizens alike. It’s emblazoned on T-shirts, used in memes, abused as a hashtag. It’s never been more ubiquitous and, as a result, more confused and manipulated. After a yearlong battle for its meaning and ownership, “fake news” is now both an empty slogan and a deeply troubling warning sign.

The story of “fake news” symbolizes how our current information environment operates and is manipulated, how reality itself is shaped and bent. It’s a testament to the fact that today a phrase or image can come to mean anything you want it to, so long as you have enough followers, propagators, airtime, attention — and the ability to coordinate all of them.

If you marshall these elements you can literally brand real things as fake. Repeat it often enough, and you manufacture reality for a portion of the population. Fake news means what your side says it does.

The paradox at the core of “fake news” getting famous is that what I think of as actual fake news — the stuff I’ve been weirdly obsessed with for at least three years — has become a sidebar in the discussion. Encouragingly, there is without question more interest, research, and public discussion about online misinformation and propaganda than ever before. Alarmingly, and as a direct result of its presence in the public conversation, it has become a politicized, polarized topic. This jeopardizes our ability to confront it.

Not being able to focus on actual fake news is a symptom of the ongoing collapse of a shared sense of reality and the related public conversation. Online misinformation, and the exploitation and manipulation of our information environment, are real, complex problems affecting global societies. By making the term "fake news" ubiquitous and muddled, we lost a battle in the actual war against completely false information.

I recently reread my 2015 research paper about rumors, misinformation, and fake news. Though it dealt with serious falsehoods involving Ebola and ISIS, it reads as being from a different time, divorced from the current reality where reality itself seems under attack.

This week, two colleagues and I published a detailed analysis of 50 of the biggest fake news hits on Facebook in 2017. We showed that, even after a year of concerted effort by Facebook and major fact-checkers to battle this specific kind of misinformation, the stories in the 2017 list generated even more total engagement than those in the top 50 of 2016. “Fake news” is everywhere in the public discussion — but people seem to forget that fake news continues to run rampant.

Our story was posted to the BuzzFeed News Facebook page. As of this writing, it has a single comment: