Last week, the popular Instagram account of @LilMiquela — aka Miquela Sousa, a 19-year-old Brazilian American model, influencer, and singer with more than 1 million followers — was hacked by a blonde and blue-eyed pro-Trump troll named Bermuda, or @Bermudaisbae. Bermuda wiped Miquela’s account clean and replaced her 150-plus posts with demands for “fake a*s” Miquela to come forward and tell us the truth about who she really is.

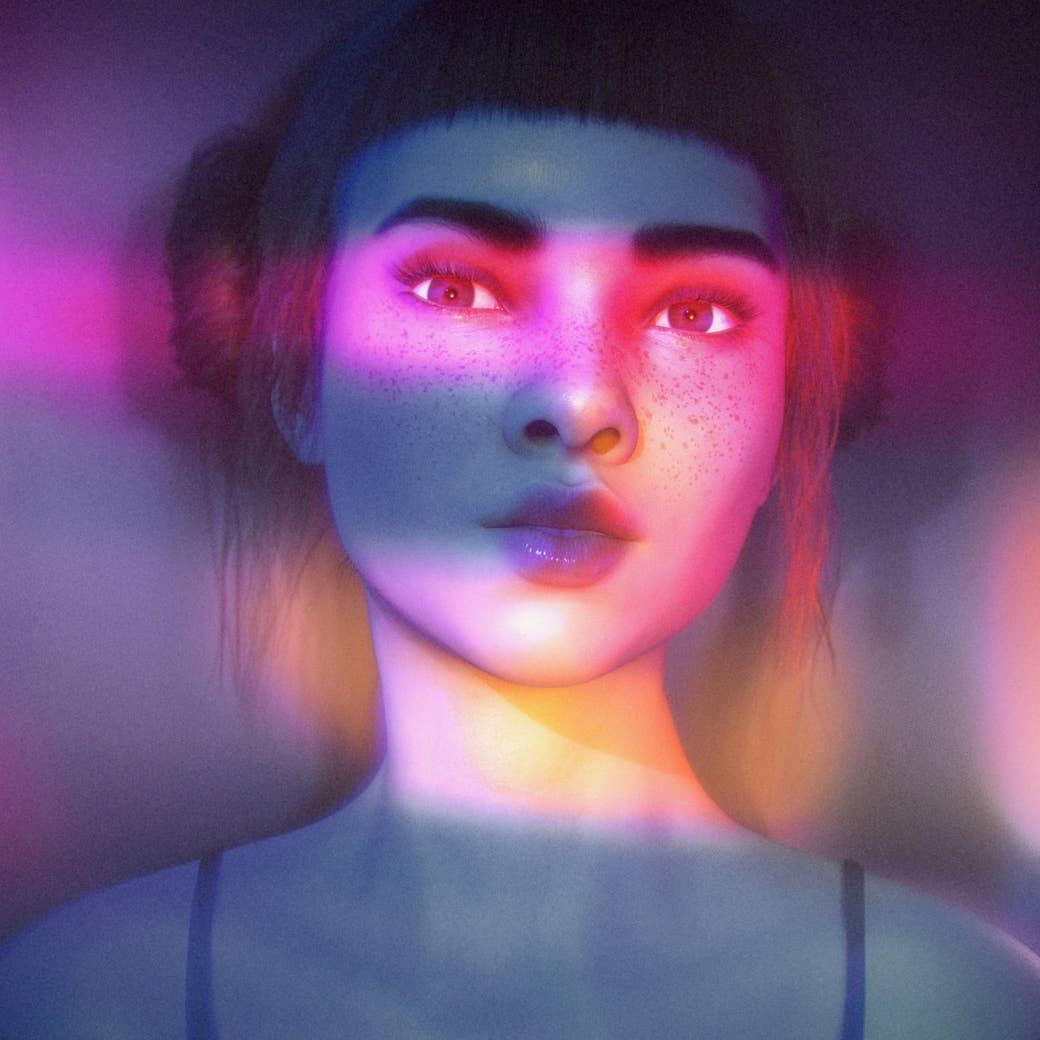

This isn’t the first time Miquela has been pressured to reveal herself. Fans have been debating Miquela’s “true” identity since her account was created in 2016 because, despite seeming like a standard millennial “IT” girl on Instagram — with blunt bangs, tiny sunglasses, and “woke” politics — Miquela is very obviously (to most people) not human. She’s a 3D computer-generated avatar. And so is Bermuda.

Following news of the hack, hundreds of thousands of curious Instagram users tuned in, responding to each carefully curated update like they were watching a WWE smackdown. What would happen between these two virtual celebrities from seemingly different planets — one who uses her platform to support gun control and #BlackLivesMatter, and the other a climate-change denier who says her “safe space” is the mall?

The hack lasted about a day, at the end of which Miquela’s account was restored and everything went back to normal for her followers, who were (understandably) confused. Those who have been following the hype now know that the company behind Miquela is Brud, a Los Angeles-based robotics and AI startup cofounded by “Head of Compassion” Trevor McFedries, an engineer and former music producer, and “Chief of Stuff” Sara DeCou. While Brud hasn’t publicly admitted to also engineering Bermuda, or the “hack,” if the company invented one virtual celebrity, it could easily invent another. So what’s the point of all this manufactured drama on the internet?

“People are intrigued and engaged because we’re telling fictional stories in spaces that are normally reserved for reality,” explained a source close to the company, who preferred to remain anonymous. But is purposefully wielding a false narrative, even with the goal of building “a more empathetic world and a more tolerant future,” any different than straight-up manipulation? Is it “art”?

Since her introduction to Instagram two years ago, Miquela has been famously cagey about her identity, inspiring various theories about who is behind the virtual celebrity, and why. While featured in several high-profile fashion and branding campaigns (including a collab with Giphy and Prada for Instagram), in press interviews Miquela always avoided any satisfying explanation about how and why she exists at all, claiming those details were beside the point. In a rare phone interview with YouTube personality Shane Dawson in 2017, Miquela responded to the question of whether she was a “real” girl, saying, “I keep getting asked if I'm real or fake. But I'm really here, I'm really talking to you. I'm really DM’ing people. I'm just trying to make some great art and make the world hurt less.”

It seemed like the two-year-long search for answers regarding Miquela’s identity was about to end last week when, following her “meet-up” with Bermuda, Miquela made an emotional announcement to followers in the mode du jour of so many celebrity confessions: an iPhone note screenshot and posted to Instagram. In her note, Miquela admitted that she is, in fact, not human. Obviously, OK, but there’s a twist. If we are to believe the narrative laid out for us by Brud on Instagram, then Miquela is a robot built by Cain Intelligence, a mysterious, Trump-endorsing Silicon Valley company that designed Miquela to be a servant and also built Miquela’s “hacker” and ideological nemesis, Bermuda (also a robot).

It doesn’t seem real, because it’s not. Cain Intelligence is fictional, and Miquela and Bermuda are CGI, not robots. But the creators at Brud are optimists about the effect their fantasy story could have. (Who wouldn’t be an optimist after a rumored $6 million investment?) “Fiction as reality has staying power,” my source told me. They referenced the effect Will and Grace had on American attitudes toward gay people as a recent example of the transformative power of storytelling in the media.

Of course, it’s hard to believe in 2018 that anyone still trusts social media, especially a visual platform like Instagram, to reflect “reality.” Miquela said as much in her interview with Dawson last year: “Can you name one person on Instagram who doesn’t edit their photos?”

It’s hard to believe in 2018 that anyone still trusts social media, especially a visual platform like Instagram, to reflect “reality.”

We use platforms like Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, and Facebook because they allow us to magnify only the parts of our lives we want to be seen, while at the same time presenting these parts as our whole, authentic selves. The Kardashian/Jenners are a famous example of how to make this equation successful for you financially, and Miquela has already been compared to Kylie Jenner, who successfully converted the 100 million followers invested in her “authentic” self on Instagram (and Snapchat) into customers for a multimillion-dollar makeup line.

The genius aspect of all this robot drama is that — at least for the moment we’re in right now — it doesn’t really matter whether we believe Miquela is truly a robot rather than a digital avatar, or whether Cain Intelligence exists in the real world the same way that Brud exists. (It doesn’t.) The narrative being developed with each new Instagram post is already succeeding because we’re paying attention to it. At the end of the day — whether we’re entertained or aggravated by Miquela’s virtual celebrity — we keep asking questions, and we keep tuning back in to find out more. We’re arguing about Miquela and becoming emotionally involved. While it’s a way of creating discourse on the internet, it’s also the same strategy manufacturers historically used to sell cleaning products during serialized daytime television shows. There’s a reason they’re called soap operas.

Much like Jenner, who builds illusory insight into her private life with each curated selfie, the source I spoke to said Miquela employs “panel-by-panel storytelling.” It’s also classic American superhero stuff for the mobile-first generation. There’s the fictional executive Daniel Cain, whose figure is literally cast in shadow on the Cain Intelligence website — a sort of Lex Luthor-type villain. Then there’s the emotional drama of Miquela discovering she and her archrival Bermuda are both supposedly his creations, which seems like a pretty clear allusion to Luke Skywalker’s daddy issues to me, and I don’t even like Star Wars.

Remember that comic book superhero sagas, like folktales and religious parables, are fundamentally moralistic: They pit Good in the fight against Evil, and in the US that story never gets old. On one level, it seems the narrative that Miquela and Bermuda originated from the same fictive creator is intended as an instructive metaphor for contemporary bipartisanship — in other words, whether we identify as liberal or conservative, we’re all human and we’re all flawed, so we might as well #LearnToTalk (as Bermuda puts in her Instagram captions).

On another level, it’s fascinating to consider how this fiction parallels truth, since in reality Miquela and Bermuda are made by the same people: Brud. They’re already telling us so, in a way. It’s an acknowledgment that comes through an interstitial layer of fantasy, yes, and it’s nowhere near full disclosure, but maybe their noble intentions are enough to justify the invention of a functional Trump troll in the real world. Brud seems to think so.

If the Trump presidency has taught us anything, it’s the power of narrative. There might be no place in the world that understands this better than the entertainment industry, where former movie producer and later Breitbart News head Steve Bannon first discovered the tools he needed to thwart the Clinton campaign via heightened emotional stakes and #FakeNews. It’s interesting that Brud also has roots in and around Los Angeles, where founder McFedries formerly worked as a manager and producer to music talent like Banks, Katy Perry, and Sky Ferreira. And, not totally dissimilar to Bannon, the real people behind Miquela seem to view themselves as outsiders to the established system.

The actual question behind all this, the source close to Miquela’s creators said, was whether there exists “an opportunity to create media that can touch billions of people.” Additionally, “Can it influence billions of people to be better people?” The way they understand the internet frenzy they’ve so far engineered through Instagram, they are something like virtual Robin Hoods, “cyberpunk” millennials interested in repositioning the worlds of tech and global media as vehicles for a different outcome than what we seem headed for in 2018: a lonely, dystopian mess, something we no longer believe in.

It’s sort of like a mental physics equation — the idea that the trend of distrust and intolerance on the internet might be written in reverse using the same tools. And at least in the virtual world of Miquela, it seems (maybe) to be working. Before the hack, the majority of Miquela’s followers appeared dedicated to unmasking her “fakeness,” although some were more sweepingly positive, leaving behind an endless trail of fire and heart-eye emojis in their wake. The “Miquelites,” as they’ve been identified by some, seemed totally on board with the way Miquela’s online persona revealed what they already knew: No one is “real” on social media. For once, they were in on the joke; they were no longer being deceived.

Since the hack and her official coming out as a robot, Miquela has received an outpouring of emotional support that’s startling, precisely because Miquela doesn’t, strictly speaking, experience any emotions that need supporting. “I am not human, but am I still a person?” Miquela mused to followers on Instagram, admitting to feelings of anger, fear, and loneliness following recent revelations, to which @julia.dig responded, “You're not alone my Spanish class loves you.”

The Miquela experiment might very well be succeeding, but what are the parameters for success, and who sets them?

By the looks of it, Miquela is starting to feel a little better, or if not better then at least #grateful for some of the lessons she’s learning as a result of her identity crisis. “In trying to realize my truth, I’m trying to learn my fiction,” she posted last weekend, along with a selfie of her looking glum at home while sporting her signature Princess Leia (!) buns. “You are a inspiration xxxxx love you,” commented @sparkle._.daisy later. Once Miquela returned to the platform after turning her phone off all weekend to clear her mind, @ness.escobar commented, “I hope you’re feeling better :gift_heart: #robotfeelingsmatter.”

The Miquela experiment might very well be succeeding, but what are the parameters for success, and who sets them? “I will never forgive them,” Miquela wrote last week, referring to Brud’s role in creating her persona and concealing her “true” identity from her. On Thursday, maybe signaling where her story will be heading next, she wrote in a caption, “I’ve been really stressed since I’m no longer working with my managers at Brud.” But another comment from @alexandria.staehr on the same post — a photo of Miquela wearing a crop top and gingham on a street bench — suggested that the marketing potential of Miquela’s platform remains intact: “What skin care do you use?”

Asked what will come next for Miquela, my source wouldn’t comment except to say, “Miquela’s struggle for robot rights will be a parallel for civil rights.” When I asked why there was so much secrecy about Miquela’s origins and the comic-book narrative that’s unfolded around her, they replied, “If I show you how the magic trick works, then the magic is less effective.” It’s certainly an interesting vision, and perhaps a well-intentioned one, to propose that by controlling our access to the “truth” about Miquela, we might be freed to become more tolerant of one another. The thing about “magic,” though, is that it relies on manipulation. Ask any professional magician. ●